When visitors first enter the JCNM, they encounter a panel couched in a stack of shipping sacks and suitcases; although the authenticity of the suitcases was not noted anywhere, they are immediately emotive. At the centre of the room, set among the stack of suitcases, a television screen is set up to show videos. Carter included the suitcases in order to give more depth to the photos, believing that photo exhibit on its own was too stark. The decision to include the videos along with the exhibit essentially “activate[d] the gallery.” The video Pilgrimage documents the Japanese American experience and the now-yearly visits made by Americans of both Japanese and non-Japanese heritage to the memorial monument at Manzanar. The film also connects the Japanese American experience to the post-9/11 “security” measures of racial profiling imposed by the United States.

When visitors first enter the JCNM, they encounter a panel couched in a stack of shipping sacks and suitcases; although the authenticity of the suitcases was not noted anywhere, they are immediately emotive. At the centre of the room, set among the stack of suitcases, a television screen is set up to show videos. Carter included the suitcases in order to give more depth to the photos, believing that photo exhibit on its own was too stark. The decision to include the videos along with the exhibit essentially “activate[d] the gallery.” The video Pilgrimage documents the Japanese American experience and the now-yearly visits made by Americans of both Japanese and non-Japanese heritage to the memorial monument at Manzanar. The film also connects the Japanese American experience to the post-9/11 “security” measures of racial profiling imposed by the United States.

Carter notes that these suitcases and videos help to further contextualize the photos and “set the scene” while each photo bears only short captions to “help narrate the story.” Her intention is for the photos is to “speak for themselves,” allowing visitors room to interpret meaning for themselves. On the other hand, Bill Jeffries, who was the curator for the Presentation House Gallery exhibit, feels that photos should be accompanied with more text; but of course, the creation of such text requires additional time and research.

In the theory of Roland Barthes, photographs speak the truth; the existence of a photo indicates that whatever is represented must have existed or have happened. The photos of Adams and Frank tell many stories: the story of removal and confinement, the story of the photographers themselves, the purpose for which the photos were taken, and the memory they now hold. Carter comments that “because photos are so compelling for people, they can pull you in and make you start thinking about things in different ways.” While the photos may tell one part of the story, “the best version [of history],” according to Jeffries “is when you have the photograph and you have the story, and if both of them are more or less accurate, that’s about as close as you can get.”

Frank’s photographs of beds in horse stalls—and of mothers with young children doing laundry on animal exhibition grounds – may be clinical in style, but they expose the inhumanity of Canada at that time.

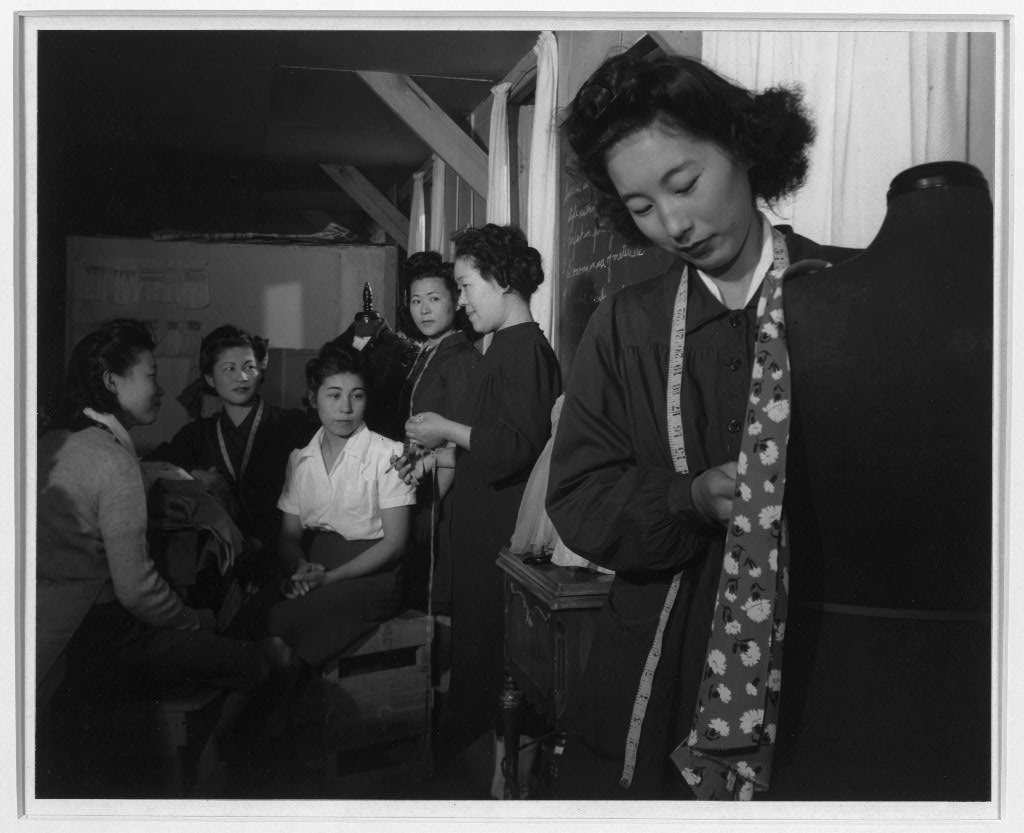

The representations in the Adams collection are problematic. Jeffries believes this difficulty is in part, “because the package as one receives it is one in which the biggest critic…has to be showing what’s going on instead of some quasi-idealistic version of what’s going on. And, because he [Adams] would have seized the opportunity to be critical of what’s going on.” What results is a series of photos that show people playing sports and gathering in the local shop, seemingly enjoying themselves. In addition to the positive portrayals of the internment experience, Adams’ photos were also artistic. Nichola Ogiwara, program coordinator and museum assistant at the JCNM, comments on the reaction of visitors. “People think the photos are beautiful, but then it seems as if they have a funny feeling about saying they’re beautiful because the subject matter is quite dark, it is negative, really…so I think there is a contradiction that people feel.” Adams took the photos in order to make a record of the experience, but he also took them in order to show the spirit and resilience of the people, despite all the hardship. Adams himself wrote, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment.” He was welcomed to Manzanar by those in charge of the camp in 1942 to take the series, partly in order to record the success of their camp and, despite his own critical reflection, he seems to have done that.

On the other hand, the Frank collection is somewhat less positive and less artistic. This is not to say they are bad photographs; indeed, they’re well done. The difference is one of style and perhaps intention. Taken for the B.C. Securities Commission, Frank’s photos were obtained as a work contract. As a result, they are a much more clinical look at the process of removal and confinement. The photos from this portion of the exhibit, which composes about 70% of the photos on display, were originally collected into an album with caption labels typed onto the back; labels such as “Building A – Baggage Room (formerly horse show building).” The remaining photos were taken at the camps in interior B.C. and were not a part of this album. Yet they also have a certain quality of documentation, without showing elements of the human spirit.

Both sets of photos were taken as representations of an event which happened at a time when the general feeling towards those of Japanese descent was racially-based fear or disdain. Photos were officially sanctioned to represent the “success” of the governments, and in doing so, they document official narratives. As Thy Phu, professor of English at the University of Western Ontario, argues, “Only by re-visioning official photos can one examine more directly the brutal ends of internment and dispersal policies.” Perhaps in “re-visioning” the two sets of photographs now, a viewer might also begin to make comparative arguments about the two countries. One might perceive the Canadian experience to have been less sympathetic with the conditions of the internment, indeed being harsher than in the United States. For the B.C. Securities Commission and for Frank, it was simply a job—one that had to be done quickly and efficiently.

Both collections, however, expose to some extent the fraudulence of the need to remove and confine the Nikkei due to their risk to national security. Frank’s photographs of beds in horse stalls—and of mothers with young children doing laundry on animal exhibition grounds – may be clinical in style, but they expose the inhumanity of Canada at that time. Adams, while not exposing any brutality, does use his photos to reject the idea that the Japanese Americans might have been spies. In photographs such as the one entitled “Ray Takeno’s desk”, in which, upon said desk there are only books in English, including a text on the American Revolution, Adams seems to be showing us that Japanese Americans were the same as any other American at the time.

In the navigation of the past, “[the photograph] does something that words can’t do” says Ogiwara. Summed up in this short statement, this is the value of these photographs as a record of the Nikkei experience in both Canada and the United States. More than aesthetically good photos that draw people in, they stand as historic records and evidence of these camps. These photos also capture the story of racial discrimination; showing us what we are capable of in times of fear and prejudice. But above all, they are depictions of the resilience of the human spirit.

Subscribe to Ricepaper, to get your quarterly fix of Asian Canadian cultural awesomeness.