Terry Woo’s first novel emerged in 2000, right at the start of what has been termed the Pacific Century and getting shortlisted for the Asian-Canadian Writer’s Workshop Award in the process. The book has since become a cult classic of sorts and has spawned a play by the Factory Theatre in the process. It was a breath of fresh air when it was first released, garnering interest for its portrayal of uncomfortably relatable Chinese Canadian not-quite men trying to lead normal lives while being stuck between two worlds. Sixteen years forward, the book still manages to remain as relevant, incisive, and contemporary as it did in the past, and definitely warrants a second reading.

Enter the titular Banana Boys-Luke, Dave, Sheldon, and Mike-who converge after the apparent suicide of their de facto leader, Rick. “Yellow on the outside and white on the inside”, they all struggle with questions of identity throughout the book, and remain vaguely messed up from their first meetings at the University of Waterloo right up to the funeral. Luke is a DJ in Toronto, seemingly drifting with the wind, while Dave is an abrasive software tester and an unapologetic chauvinist. Sheldon lives a stereotypical Good Boy life and works an uninteresting routine job in Ottawa, while Mike is stuck in a graduate program he does not want, straining to write The Book out of ideas kept in a Cambell’s Soup book. Even Rick, the richest and most successful of the group, was an alcoholic and Pyloxodin abuser until his untimely death, forever driven by the need for fame, money, and girls.

Besides being filled with questions of ethnicity (which the grudging Dave constantly gripes about), love and relationships form the other core theme of the book. All of the Boys have had dysfunctional or barely-existent relationships, and huge swaths of their conversations end up revolving around girls and the obsessive quest for true love. Dave and Sheldon in particular are on opposite ends of the spectrum; while Dave’s angry affairs send him spiraling into racially-charged rants on Sexloverelationships, Sheldon begins a short but poignant one with a student in Ottawa. Meanwhile, the Boys’ bittersweet family relationships are not as visible by comparison, but ultimately they are always present in some form or another.

It’s worth noting that the book is told almost entirely from the perspective of the Boys-the only female voice that emerges is Rick’s sister Shirley, who witnesses his mercurial rise and fall. She also sees the Boys as who they really are-flawed young men trying to find their way in the world, even outwardly successful ones like Rick.

Terry Woo’s prose zips along with nervous energy, drawing out a world of failed love stories and personal insecurity from Ontario to New York. The characters are well drawn and you can easily see them drinking in bars, getting into fights, or slaving away at scientific research. Although the Boys are all geographically scattered and leading different lives they find themselves reminiscing about each other constantly. It is this need for proximity that further defines the characters. Neither Asian nor white, they are united by their shared differences rather than similarities. But despite the heft of the societal and cultural issues covered in the book, it has a manic and over-the-top humor to it. Explosive descriptions and piercingly blunt observations converge in a self-aware deconstruction of the familial drama and history present in mainstream Asian American/Canadian stories (“if you want that shit, rent The Joy Luck Club” as Dave snarkily points out early in the story). Banana Boys is a book about confused young men in the here and now, still uneasily trailing cultural baggage behind them.

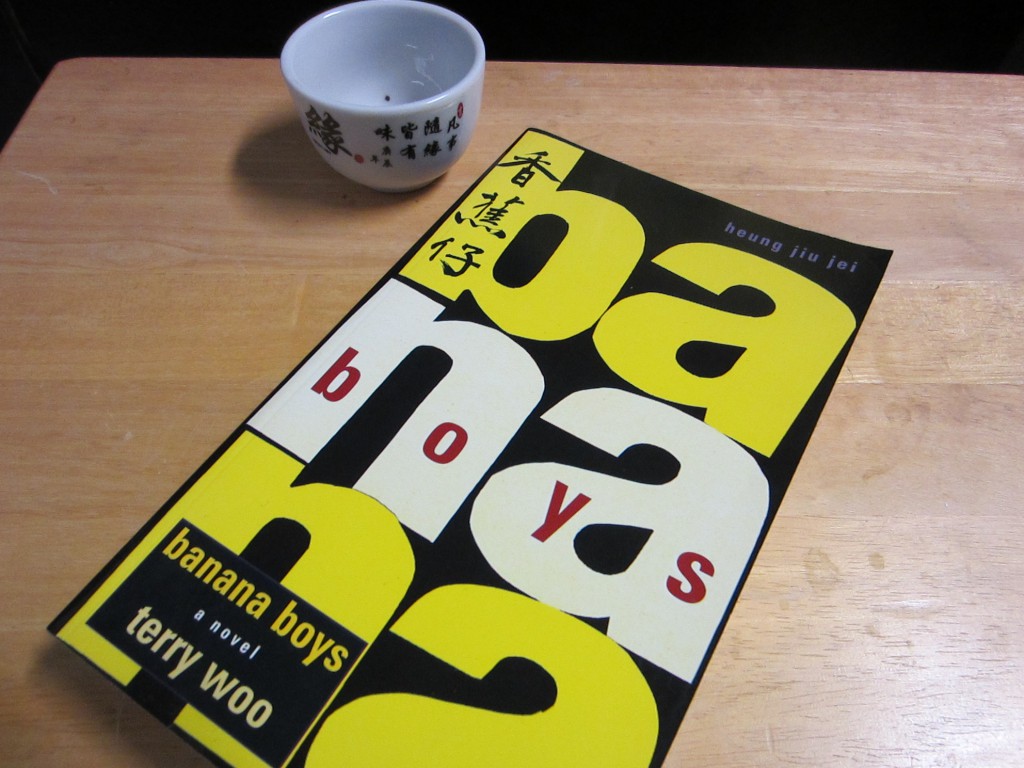

Banana Boys can be bought online, or in various bookstores and libraries. Photo by William Tham.

1 comment

The first Banana Boys review in Ricepaper: http://www.bananaboys.com/reviews/ricepaper_review.htm

Banana Boys

Terry Woo

The Riverbank Press

review by Michael S. Chong

Terry Woo’s debut novel, Banana Boys, is about these Canadian-born hosers of Chinese descent and the minute details of their relationships with their loved ones. The cast includes Luke the liberal DJ wanderer, Dave the racially-obsessed computer-dating analyst, Mike the depressed wannabe writer, Sheldon the good-boy engineer, and Richard the prodigal faux FOB (Fresh Off the Boat). These are characters I’ve met in real life but, until now, never in pop media. Woo gives each a strong voice, and they grow and mature as the narrative unfolds.

I recognized shades of myself in each of the banana boys: the parental unit face-factor, the post-Head Tax bachelor society, the fight against prescribed stereotypes, and the underlying search for identity. Reading Banana Boys was like looking into a mirror and wincing. But as Luke says to Michael, “Healing is the best revenge.”

The book opens with a tragedy which reunites the group, then flashbacks which reveal the growth of their relationships. Each chapter is told by one of banana boys, as they try to build lives in the Great White North.

Through the course of the novel, Woo’s characters try to attempt to answer the introductory question:

“You’re not Chinese and you’re not white . . . what the hell are you?”

One of the major quests for the banana boys is to find their idealized banana girl. The women of Asian descent play supporting roles in the book, except for Richard’s sister, Shirl, whose observations open and close the book. None of the positively-portrayed banana girls have a banana boy boyfriend or husband. But then again, if I remember correctly, neither did any of the women in Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. Tan’s novel is mentioned several times in Banana Boys, usually with derision. Richard tells Michael he should include Chinese mysticism in his planned novel because it made books like Tan’s bestsellers.

In fact, Banana Boys could be seen as an answer to The Joy Luck Club and its progeny. The structure is similar but instead of a round of mah-jong, the banana boys, like good Canadians, sit around cherishing the amber ambrosia of Canadian lager. Another difference is that none of the banana boys have a successful relationship with the opposite sex.

The older generation of Chinese parents are also background players in the story. The fathers are either absent, as Luke’s is, or weak, as Richard sees his depression-addled father. The mothers are stringent and controlling, for the most part, with guilt as a major tool.

In the end, there is hope, with some of the banana boys opening the possibility for both romance and travel. They are finding their way away from a state of learned helplessness. To be a man, with all the positive and negative connotations of the title, in an emasculating situation may be what lies beneath the peel of Terry Woo’s Banana Boys.