Kathryn Ma’s ‘The Year She Left Us’ opens with Ari-full name Ariadne-wandering a maze of conflicting identities. Abandoned in a shopping mall in Kunming, China, she finds herself adopted by the loving but fragile Charlie, a lawyer based in San Francisco. Ari is just one of thousands of orphans, almost entirely girls, making the strange migration from east to west in the wake of disastrous Chinese policies. She is just one of many ‘Whackadoodles’ trying to adjust to new lives with the promise of heritage tours to the motherland and their orphanages always down the pipeline. From there Ma’s delicately constructed world expands to the rest of Charlie’s family. Lesley, her sister and judge, presides over court cases that threaten to destroy her support from the Chinatown community, and their mother, referred to as Gran for the most part, is aloof and stern, racing down the roads of South California and haughtily reflecting on her upper-class upbringing in Hangzhou before being uprooted by the war in China. Ari drops right into the frayed relationships of the Kong women, and its unraveling and underlying chaos is triggered when she eventually runs away.

Kathryn Ma’s ‘The Year She Left Us’ opens with Ari-full name Ariadne-wandering a maze of conflicting identities. Abandoned in a shopping mall in Kunming, China, she finds herself adopted by the loving but fragile Charlie, a lawyer based in San Francisco. Ari is just one of thousands of orphans, almost entirely girls, making the strange migration from east to west in the wake of disastrous Chinese policies. She is just one of many ‘Whackadoodles’ trying to adjust to new lives with the promise of heritage tours to the motherland and their orphanages always down the pipeline. From there Ma’s delicately constructed world expands to the rest of Charlie’s family. Lesley, her sister and judge, presides over court cases that threaten to destroy her support from the Chinatown community, and their mother, referred to as Gran for the most part, is aloof and stern, racing down the roads of South California and haughtily reflecting on her upper-class upbringing in Hangzhou before being uprooted by the war in China. Ari drops right into the frayed relationships of the Kong women, and its unraveling and underlying chaos is triggered when she eventually runs away.

Ma’s novel is a mashup of sorts. It is a fable of a girl without a past looking for one as she wanders through the suffocating atmosphere of south China and to the purifying, icy wastes of Alaska. It is a legal drama mired in race politics and righteous anger. It’s the story of a stern woman trying to keep her immaculate life from falling to pieces. It can be muddled, overlong, and messy. But at its heart it’s the story of daughters from three different generations coming to terms with each other. Ma’s elegant, precise prose shows hearts being broken and betrayals being notched. Ari drifts in and out of the unease, seemingly indifferent but ridden with angst and nursing a maimed finger as she tries to place names and faces to an unknown father while growing increasingly hostile towards her adoptive mother. Oddly enough she connects well to Gran, whose cold, domineering nature is the perfect foil to Ari’s waywardness as she delves into stories of her past in the misty heights of Lushan and the glamourous depths of Shanghai before the war.

In our recent review of Banana Boys, one of Terry Woo’s characters pointedly mentioned that his story was about people in the here and now. Ma’s novel harkens back to the traditional background of the Asian-American/Canadian novel, significantly delving into history. Perhaps it is emblematic of the Asian diaspora in North America in general: Drifting, trying to find an anchor in the past. This is the central tenet of Ma’s novel, and it is achieved with a melancholy triumph.

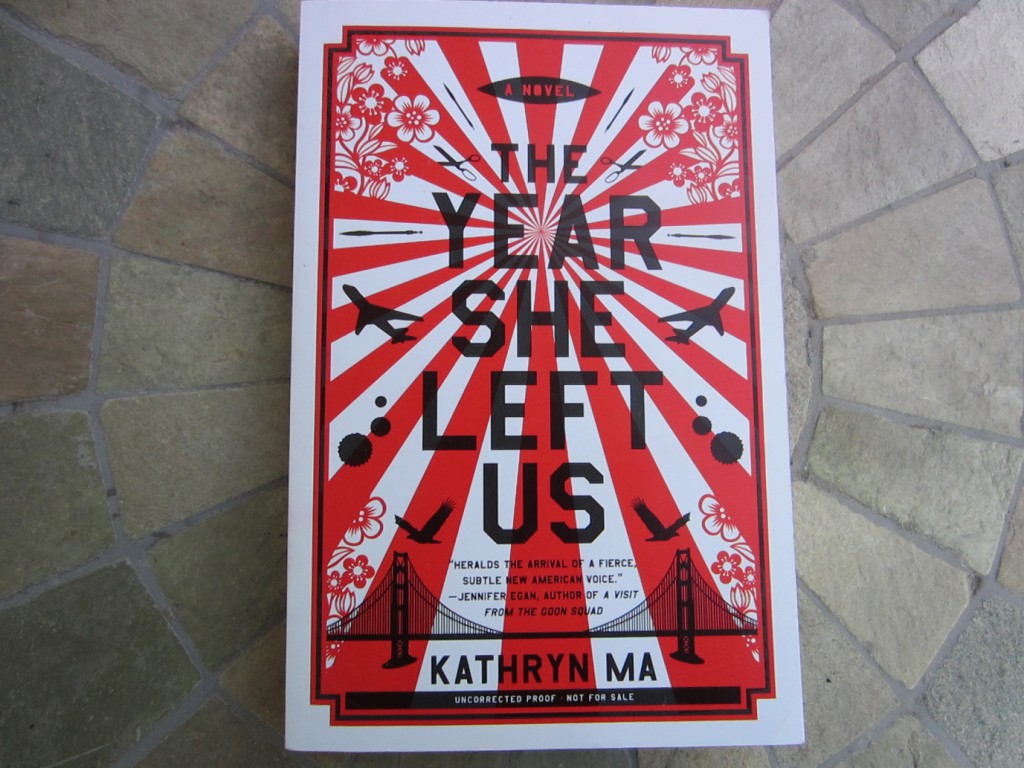

Photo by William Tham