As a visual artist working across multiple mediums, with an affinity for photography with found and readymade objects related to the Chinese diaspora, Yow’s work often includes the portraits of artists in the community, many of whom you might even know. Clare completed her M.F.A. Visual Art thesis, “A Question of Priorities: Unmapping Through A Diasporic Femininity,” at the University of British Columbia in 2010. Over the last number of years, Clare has divided her time between gently growing her artistic practice and engagement in social activism, volunteering and freelancing for non-profit organizations, and most recently, working full-time in higher education. Ricepaper interviewed Clare as part of its profiles of emerging Asian Canadian artists.

As a visual artist working across multiple mediums, with an affinity for photography with found and readymade objects related to the Chinese diaspora, Yow’s work often includes the portraits of artists in the community, many of whom you might even know. Clare completed her M.F.A. Visual Art thesis, “A Question of Priorities: Unmapping Through A Diasporic Femininity,” at the University of British Columbia in 2010. Over the last number of years, Clare has divided her time between gently growing her artistic practice and engagement in social activism, volunteering and freelancing for non-profit organizations, and most recently, working full-time in higher education. Ricepaper interviewed Clare as part of its profiles of emerging Asian Canadian artists.

Your work is foregrounded on the everyday, readymade, and seemingly unremarkable as “subject matter, material, and process.” How does your art practice and research interests serve as an ongoing negotiation and reconciliation with your personal politics of identity and belonging?

As a child yearning to assimilate into Canadian culture, I fought hard to shed any markers of my Otherness – be it my accent or denying that I attended Saturday Mandarin school to classmates. Because my family never really discussed the complexities of the immigrant identity, in some ways, I was left to fend for myself in untangling what it meant to be racialized and gendered. It wasn’t until late in my undergraduate studies in Toronto that I came to the gradual realization that reclamation of my Chinese heritage was vital for my growth as an adult. It was necessary to confront why I decided assimilation needed to be at the expense of my Chinese heritage.

Being in grad school in Vancouver allowed me a safe space to explore my identity through the concepts of shame, silence, and invisibility. Art as a vehicle gave me permission to delve into the notion that the subjectivities I embody – as a woman, a person of colour, an immigrant, a settler – together with my lived experiences, all have tangible weight in this world. It is a continual process of raising social consciousness through the lens of having this particular skin.

Your latest exhibit was Body Talk at The Beaumont Studios, which took place from September 21 to October 5 in Vancouver, BC. What can you tell us about this exhibit?

Curated by Maxim Greer, Body Talk was a group exhibition based on various artists’ abstract and figurative representations of the corporeal, spanning mediums such as painting, drawing, and collage. The pieces created a dialogue around objectification and the human body.

Curated by Maxim Greer, Body Talk was a group exhibition based on various artists’ abstract and figurative representations of the corporeal, spanning mediums such as painting, drawing, and collage. The pieces created a dialogue around objectification and the human body.

I exhibited selections from my series “Descent/Consent,” where phrases uttered to me in fleeting public interactions were impressed directly onto my own skin and photographed. I have collected these examples of microaggressions for years but didn’t begin making sense of why they were strange really until grad school. That’s around the time I read Ien Ang’s work and the title of this series is a nod to her. She writes in her book, On Not Speaking Chinese: “If I am inescapably Chinese by descent, I am only sometimes Chinese by consent. Where and how is a matter of politics.

What does it mean to be a female Singaporean-Chinese visual artist in Vancouver?

I’m not entirely sure if I can distill what such a position means, if anything! Vancouver has been my home for more than eight years and I feel heartened that great initiatives in arts, cultural heritage, and social justice that involve women and other folks from the Asian community exist (such as The Future is You and Me, Hua Foundation, Asian Diaspora on Unceded Coast Salish Territory, and yes, Ricepaper too!). Diverse voices are helping further the discourse on pertinent local and global issues. On being Singaporean-Chinese in the city, I will say that my head always whips around whenever I hear a Singaporean accent. It makes me beam, hearing a bit of home every so often.

What is your definition of Asian Canadian? And how does it inform your work?

Being a part of the Asian diaspora means straddling multiple continents; having a home and a continued involvement with back home. It is a rich and complex product of transnationality, but for me, it also necessitates ongoing education about and solidarity with marginalized communities.

Over the last year, I have been surrounded by incredible social activism – talking about, reflecting on, and attending rallies for Black Lives Matter Vancouver and the Break Free and Coast Protectors climate justice movements. Identity politics and social justice issues are inherently linked and my hope is to make more work that explores this relationship.

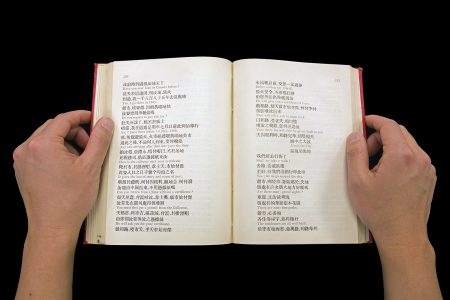

Recently, I created a new photographic series in direct response to the accomplishments and failures of the last 150 years since Canada’s confederation. Things have changed, but they haven’t changed focuses on a Chinese/English phrasebook from the 1900s. My aim was to explore the fact that our country was—and very much continues to be—built on precarious migrant labour. The works are part of an upcoming group exhibition in Prince George, BC.

I lived there before 1st July, 1886 (2016)

You’ve photographed many artists and community people. What’s the most memorable photo you’ve taken of an individual? What’s the story behind that photo?

Capturing my first niece’s birth is an incredibly strong memory. My older sister and I weren’t living in the same city, but I planned a trip to see her in Ottawa and Dawn had coincidentally just gone into labour when I arrived. Looking back at the photos almost nine years later, I am still overwhelmed by my sister’s quiet bravery and the care that her partner Lucas gave her throughout. I feel lucky to have witnessed such intimacy – not just with the birth of a person but also Dawn and Lucas becoming parents.

Of all the photos I took that night, the details in this image stand out: Raspberry—wrapped in the standard hospital blanket—her hair still matted with blood during one of their first moments of contact, and my sister’s Tuberculosis vaccination scar on her left bicep, a mark of our childhood in Singapore.

View more of Clare’s work at http://www.clareyow.com/.