We have recently started a new project to bring translated works from Asia to our readers. Thanks to the efforts of translation editor Nick Stember, we are pleased to present acclaimed Chinese author Jia Pingwa’s short reflection on a drink with his father.

Nothing On My Mind. By Jia Pingwa

After I began my work in the city, I didn’t see my father for a while. He had retired from his teaching job and stayed home to look after my daughter. I had begun to publish but I never let him see any of my writing. He eventually heard from my aunt that I had recently published a novella. He went to the county town, searching through every bookstore and post office for a copy of the magazine that published it. I was sick at heart when I heard what had happened. I began to dutifully send him a copy of everything I published. I would soon get the work back in the mail, with his notes scrawled on it. My daughter was already walking and my father began to grow worried that it had been too long since I had seen her. He sent a letter to say he thought it would be best if they came to stay with me in the city. Nothing came of it; he never arrived; he sent a picture of my daughter every month. He encouraged me to keep writing: “You’re making a living as a writer now, so put everything you have into it. When it comes time to winnow, the farmer takes advantage of every gust of wind. Take advantage of the time alone to work as hard as you can. But I have heard that you have been drinking a lot. When you were young I didn’t provide a positive example for you to follow. I’ve now stopped drinking completely.” When I read the letter, I was deeply ashamed and swore off liquor altogether. I finally sent a letter back to my father, entreating him again to live with me in the city, along with my daughter.

Not long after I sent the letter, I ran into some difficulties. Several magazine pieces I had published generated some controversy. Controversy isn’t unusual in the literary field. After all, a complicated social climate produces unusual ways of looking at the world. But then the controversy began to spread beyond literary criticism. I was deeply bothered by the things that were being said about me, and became as timid as a farmer carrying a load of eggs to sell in the city, always treading carefully. In the midst of the controversy, I decided I couldn’t ask my father to come live with us. But before I had a chance to send him a letter, he arrived. One rainy night, he caught a ride to the city and arrived on my doorstep.

In the midst of the controversy, I decided I couldn’t ask my father to come live with us.

My old father had grown frail. His eyes, which suffered from cataracts, had grown cloudier. It worried me to see him like this. He looked me up and down and set my daughter down at my feet, pointing up at me: “Papa. Call him papa.” My daughter tilted her head and looked up at me for an instant, before running back into the arms of my father. He laughed: “Look! She doesn’t have any clue who you are. Good thing I brought her, eh?” We gave them the east room of the apartment. My wife and I stayed in the west room. Our daughter slowly warmed up to us but when it came time for bed, she always returned to the arms of my father.

I made my wife promise that she wouldn’t tell my father about the controversy that had erupted. When I came home, I chatted with him, listened to his stories about my daughter. He showed her off, prompting her to perform whatever little tricks she could do. In the evening, though, there would always be a crowd in the house, people coming over to gossip about the trouble that my work had stirred up with the critics. I kept them in the west room and closed the door, reminding everyone to talk quietly. Whenever my father came in, the conversation stopped. I kept up an appearance of happiness, but there was a storm brewing outside. I had a harder and harder time keeping it together when I came home. My daughter, unfamiliar with life in her new home, acted up. One day I spanked her and my father came to scoop her up, hugging her to his chest. He scolded me, saying that every time I hit her, she would grow further apart from me. He carried my daughter off to the west room. I sat alone for a while, then decided I was wrong, but I still couldn’t tell my father what was happening. I walked over to the west room and pushed the door open. I saw that my father was crying. When he saw me, he pretended that his eyes were bothering him and rubbed at them. The pain in my heart grew sharper. After that, my father let me know he would be leaving soon

I saw that my father was crying.

Every evening, the gossip continued in the east room, and he would retire to the west room with my daughter. When Sunday came, he left a note on our door: “We won’t be home today,” and took the family out to the edge of the city for a walk. He called my daughter over, reminded her to call us, “Mama, Papa,” and then walked off by himself, saying something about going to buy candy for my daughter. It was a long time before he came back, but when he did his pockets were bulging. He gave one bag of candy to my daughter and the rest to my wife. He suggested they go play by themselves and leave us alone for a while. My father and I sat down together. From inside his coat, he pulled a bottle of alcohol and a package of braised lamb. I was confused. Hadn’t my father said he’d stopped drinking? Hadn’t he scolded me for drinking? He opened the lid of the bottle on his teeth. “Let’s have a drink, Pingwa. There’s something I want to talk to you about. You’ve been holding out on me, but I know what’s happening. That’s why we came when we did. People were saying that you’d run afoul of the rules, but they didn’t know the full situation. I got worried that you were in over your head. The other day though, when I was out on my walk, I read the paper. It’s nothing, is it? You’re too successful—little setbacks like this now just mean that you’ll be a big success in the future! I’m not saying you should go looking for trouble, of course, but you shouldn’t get too worked up about it. And don’t listen to what everyone else is saying. You know your own heart. Life goes through seasons. You can’t always walk a level road. Don’t lose hope at this point. That’s what I wanted to say to you. Now, today, we drink. Put all your worries aside and drink. Come on, drink up. I’ll have some, too.”

He drank first. His face flushed and twitched before he swallowed. He popped his mouth open wide and exhaled loudly. The look of a man who doesn’t drink but needs to drink. My hand shook as he passed the bottle to me. I couldn’t hold it. Tears slid down my face.

Come on, drink up. I’ll have some, too.

We drank half the bottle, watching my daughter play in the fields at the edge of the city. Dusk fell before we made our way back home. A few days later, my father brought my daughter back to the village. That half bottle of liquor, stayed on my desk. I’d often look at it as I wrote and, each time, feel the same sense of relief.

Five Flavor Alley, Xi’an, 1983

Note by Nick Stember: Aside from his novels, Jia is perhaps best known in China today for his short essays. Translated by Dylan Levi King, “Drinking” is an excellent example of way Jia uses small details to paint a much larger picture.

While often included within the canon of the ‘roots seeking’ (寻根) movement of the 1980s PRC, Jia Pingwa’s search for roots arguably extends further back than peers such as Mo Yan, Han Shaogang, and Ah Cheng. Finding inspiration not so much in the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, but instead in the classic novels of Chinese vernacular tradition, Jia’s fiction is characterized by dense plotting, large casts of characters who suffer dark twists of fate, and, most of all, detailed accounts of dying traditions. While by no means apolitical, Jia’s work is concerned first and foremost with the fate of the villages and villagers of southern Shaanxi, eschewing blanket statements and grand declarations in favor of allegorical accounts and pitch-perfect dialogue. He is the author of fifteen novels, including The Poleflower, Ruined City, and Happy Dreams.

Dylan Levi King studied Chinese at the University of British Columbia after returning from a semester of language study at Nanjing University. Over the next decade, he lived and worked in the People’s Republic of China, including stints in Guangzhou, Nanjing and Dalian. He has spent months in a detention facility in Datong and weeks at the Four Seasons, Shenzhen. Dylan now lives in a tidy, dull neighborhood in central Tokyo, where he spends his days eating convenience store curry, chain-smoking Marlboro Menthol Ultra Lights, reading Guo Moruo and attempting to learn Japanese. Dylan has published short fiction in various low circulation literary quarterlies and his story collection Skoal vs. Copenhagen is available online at Amazon. Dylan is currently working on a translation of Dong Xi’s novel, A Hard Slap to the Face for the University of Oklahoma Press. A long-time fan of Jia Pingwa, Dylan has been a tireless promoter of his work. Dylan’s sample translation of Shaanxi Opera will be featured in the Summer 2017 issue of Chinese Literature Today.

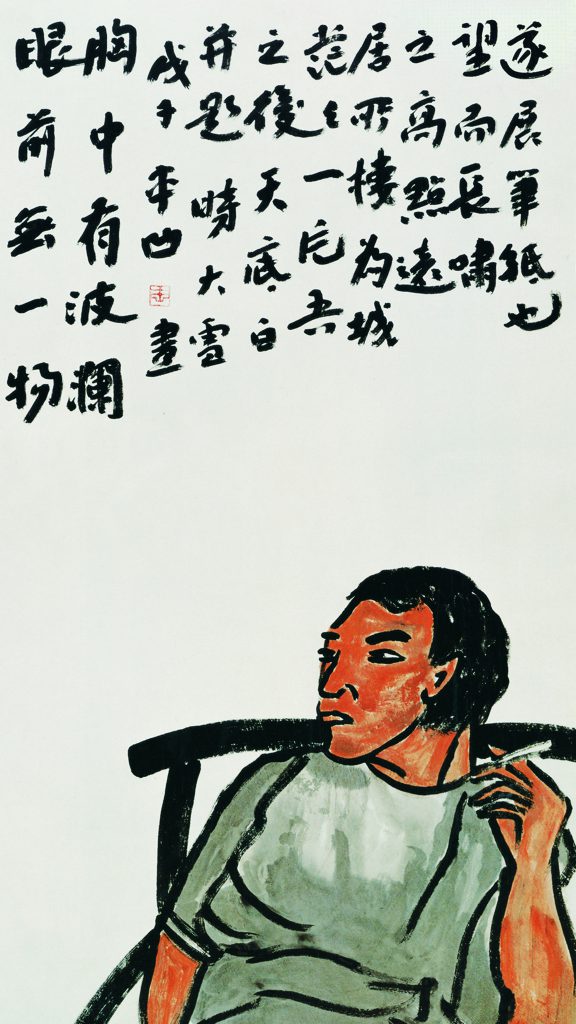

Nothing On My Mind. Painting by Jia Pingwa.

1 comment

The inscription on the painting by Jia Pingwa reads (from left to right):

眼前无一物,胸中有波澜。

Before my eyes, not a single thing,

In my mind, great waves rise and fall.

戊子 平凹画并题时

Painted and dedicated by [Jia] Pingwa in the year of the Earth Rat [2008]

大雪之后,天底白茫茫一片,

After a heavy snow, a boundless expanse of white

吾居所楼为城之高点,

My abode, the highest point

远望而长啸,遂展笔纸也。

Gazing into the distance, I curse the heavens,

Before setting my brush to paper.