In the second part of our interview with Shelly Kraicer, we discuss changes in the reception of Chinese cinema, the chilling effect of censorship and the growth of commercial cinema, the rise of black comedies, and the blurring of boundaries between documentary and narrative cinema in Chinese language films today.

Click here to read the first part of this interview, which was conducted in the media lounge of the 2017 Vancouver International Film Festival on October 3, 2017.

Shelly Kraicer, programmer of Dragons & Tigers at VIFF

❇︎

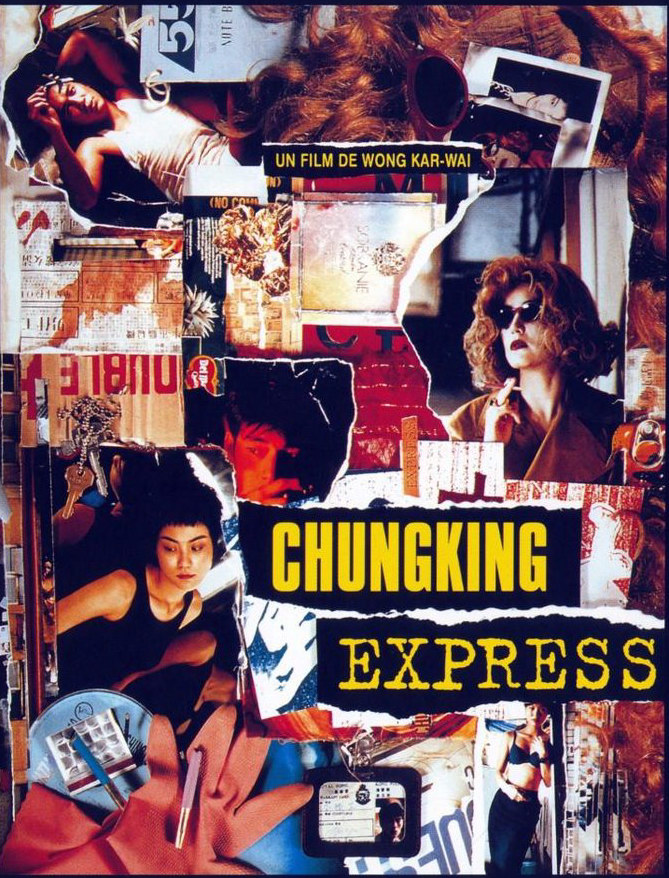

Nick Stember: In your 2014 interview with Jeremy Elphick for Four Three Film, you talked a little bit about what brought you into Chinese cinema, specifically, seeing films like Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express, Li Shaohong’s Blush and Tsai Ming-liang’s Vive L’amour in the mid-90s at the Toronto Film Fest. How do you think the place of Chinese films, or the reception of Chinese cinema, has changed at international film festivals over the two decades since? Or has it changed?

Shelly Kraicer: It’s changed a lot, definitely. Even up to the mid-90s there was an old model of experts being gateways. Which has its advantages, but usually the experts are older white guys. So it’s also an example of what is a post-colonial way of becoming a so-called expert — being a portal through which the foreign objects are deemed worthy to pass in order to circulate in the Western, non-expert circles. That’s not just in cinema, that old model applied to many fields. That was the old model, and that’s basically gone now. Through digital cinema, and internet distribution, many more people have direct or less-indirect access to East Asian cultural production. Right?

China’s not a mysterious place anymore. Or at least it doesn’t seem like a mysterious place anymore, since we’re so embedded economically, and to a certain extent culturally. So it’s not that old style model of the strange and exotic from which we can glean useful objects to become excited about. It’s much more about our relationship with China, a place we’re much more engaged with and familiar with. And so are audiences’ ability to connect with Chinese cinema for example. Rather than being mediated through other things, it’s much more direct.

Asian genre cinema used to be excluded from festivals, or occasionally showed up as sidebars such as Midnight Madness at TIFF in Toronto, or at a festival I first started working at, the Udine Far East Festival in Italy. They would do East Asian genre films. But now East Asian genre cinema by directors like Johnnie To and others is plugged into mainstream festival circuit. So there isn’t that exclusive—it’s not just Gong Li costume dramas. Or so-called ‘slow art films,’ like Tsai Ming-liang or the other Taiwanese masters. It’s much broader, it’s much less indirect. I mean, those are good things.

Chungking Express, directed by Wong Kar-wai (Hong Kong, 1994)

NS: Those are all positive things that have changed.

SK: Those are all positive things. My work as a mediator, or I think, curator, or contextualizer, I think is to help people to try to understand the context from which these really interesting films arise.

NS: So it gives you a bigger area to work in as opposed to just choosing things you think are interesting—instead you can see the things people are responding to and then provide some context to that?

SK: Yeah. I can see how China is still to a certain extent mediated in very restricted ways. You know, the standard tropes: ‘country of repression,’ full of dissident artists. That’s obviously got a substantial amount of truth to it. But that tends to be a stripped down, mono-understanding model. So I try to complicate those things when writing about Ai Weiwei or someone like that. So there are still ways to deepen and complicate, which is necessary to gain a nuanced, contextualized understanding of where this art comes from. And it matters a lot more now to people, I think. I mean, China is here. Obviously it’s present in so many ways in Vancouver, but Toronto, Europe, it’s a place we’re engaged in all parts of our lives all of the time.

So I’m hoping people understand that films from China and Hong Kong are somehow more plugged into what our lives are going to be like. In the future, or as a model for a lot of our futures. So I feel like the work I’m doing is more vital, urgent, not just art connoisseur kind of work.

There is another side, too, focusing mostly on China. The explosion of Chinese commercial cinema, since, when did the graph rapidly curving upwards? [gestures] Five or six years ago? It’s when the mass of second and third tier cities got added into a burgeoning Chinese domestic cinema distribution system. And this phenomenon hasn’t been completely positive, I think. It’s complicated. In certain ways I think it’s very positive for Chinese filmmakers. Obviously, they get a lot more opportunities to create, to make money, to get work. Terrific. To get out of Beijing Film Academy now, instead of laboring for ten years in a state-owned film studio, people hire you right off the bat. And then you can buy a car or a home for your parents, that kind of thing. That’s obviously very positive!

But films as art are almost completely submerged by films as mass, quick profit-earning commodities. So a lot of films coming out of China now are just completely boring.

NS: I remember when I was talking to Yang Chao about his film, Crosscurrents, he was saying that one of the plus sides about the way things have developed is that there just more screens where his films can be shown. So Crosscurrents was given, I think a national release.

SK: Right, a small-scale, multi-city national release. An artisanal national release, I think. They had to go city to city.

NS: Right, but he said the problem was the film was being played next to, like, Transformers. So people got mad because they went to see, maybe not Transformers, but they had a certain expectation of what they were getting into.

SK: Right, so Transformers would have been playing on nine screens, and his film would have been playing on maybe screen number ten at 11 am on a Monday. So there’s kind of a paradox. An expanding number of screens and films, but at the same time even maybe proportionally, a decreasing amount of actual, valuable screen time for films that are of artistic interest. So that obviously also affects their production, since there are very few places to actually show them. And it’s harder to attract investment to make them. And the effect on the independent film side—the 没有龙标 films [films without the longbiao, the dragon insignia that appears at the beginning of all officially approved film prints in China], 体制外 [outside the system films]—is also I think really brutal. Because young directors with something original to say, who might have lingered outside the system can immediately get hired and make films that are, whatever compromises are necessary and get them plugged into the system.

Control on independent films is more severe now. Film regulation in China has always been tight, but it definitely seems to be getting worse. So almost everyone I know who’s making indie films is trying to get a longbiao, so then they self-censor. So those films become ‘releasable,’ the only problem being where. And if they are releasable, to what extent have they censored out edginess and vitally critically sensibilities? Part of their critical voice, which they would have otherwise have partially preserved if they were working in a marginal, but I would say flourishing marginal independent film market space, which existed up until…somewhere around 2010. When authorities started cracking down on independent film festivals.

Dragonfly Eyes, directed by Xu Bing (China, 2017)

NS: My favorite take on the longbiao thing was the trailer for Xu Bing’s Dragonfly Eyes, somebody had, I think it was on a YouTube channel or something, someone had just filmed a longbiao. It was great, it was like, yeah! [hums the longbiao tune]

SK: Now that they have a real longbiao, I believe they had to remove the fake longbiao—I don’t think it’s in the current version. It was removed—

NS: It was a great bit.

SK: It was hilarious. But I’m sorry, that was a long answer to a question you didn’t ask.

NS: No, no, it’s good! Because I work more in literature than in film, and I’ve had the same issue, where on the one hand I feel like I’m always arguing with people that, you know, if I say, no there’s more to Chinese literature than stuff that’s banned in China, and at the same time you’re also heartbroken by seeing the stuff that happens, or doesn’t happen because of all the censorship. And I think what’s challenging is trying to explain the ways in which censorship works.

You were kind of getting at that too. It’s almost like it’s more terrifying the films that don’t get made than just what happens to the films after they get made. Because what happens to the films after they get made — you have this film, Have a Nice Day, by Lu Jian. So that film got made, but it was taken out of a film festival. But now it’s getting released. So eventually the film is seeing the light of day. The scarier thing is how many more films like that just never got off the ground, because people thought I’m not going to invest money in, there’s too much of a risk here.

SK: That’s right. So that’s worth explaining. But it takes a little bit of effort to tell people that that’s where the real danger is. The real losses are happening there. People think the Chinese system is still simply mired in a sort of Stalinism, this whole model of where films and other works get banned.

NS: Right, like the Feng Xiaogang film, Youth 芳华 —

SK: Right, so films like that are rare, because Feng got his longbiao. But then it was post-unapproved. Not even unapproved, just indefinitely suspended. I don’t know — I mean, I saw it in Toronto. I was a little surprised that it passed censorship. Feng Xiaogang’s very, very smart, and I thought there were profoundly critical undercurrents in the new film. But I thought he buried them and made them diffuse enough that, as he always does, that he would easily get away with it. But I guess maybe he didn’t.

NS: Right, so I remember people were saying Feng’s earlier film, Back to 1942 一九四二, was actually meant as a commentary on the Great Leap Forward and the famine which came afterward. But he couldn’t make a movie about that.

SK: Right, so he displaced all of that feeling onto a thing he could talk about. But people get it. And now he’s gotten into some sort of trouble with this new film, Youth, which portrays the China-Vietnam War as a horrible and unmitigated disaster.

Sometimes it’s just marketing. It would have been nice to show Youth here in Vancouver, but we were unable to secure it from the distributor.

But then again though, that just feeds into what people think. It’s complicated! And it’s not what I want to talk about and it’s not what I want to write about. And as I was saying, before 2010 I could easily have said ‘It’s complicated!’ and pointed to all the marginal spaces that were gradually, tentatively opening up. But now I have to write, ‘Well you kind of have the right idea, repression rules, and I can inflect your detailed understanding of this basically right idea.’ But Xi Jinping-ism is less interesting to write about than Jiang Zemin-ism or Hu Jintao’s whatever-ism. Stasis, I guess?

The Great Buddha+, directed by Huang Hsin-yao (Taiwan, 2017)

NS: You’ve got something of a repeat appearance from last year’s festival with Huang Hsin-yao’s The Great Buddha+, produced by Chung Mong-hong 鍾孟宏 whose film Godspeed 一路顺风 was one my favorites when I caught it at VIFF last year. This also another crime film, and a comedy. Are drawn to these types of films, or is it more a reflection of the kinds of films that are being made in Taiwan and other Chinese speaking countries at the moment?

SK: Well, if you liked Godspeed you may like The Great Buddha+…but I’m not particularily drawn to black comedies, no. I just think there are a lot of good ones these days, from China, from Taiwan. The Great Buddha has another Chung Mong-hong connection by the way. The cinematographer [Nagao Nakashima], it’s a name that looks Japanese. But actually its Chung Mong-hong’s Japanese pen name. So he’s the cinematographer. So many of my Taiwanese friends saw his involvement in the film was a key way to understand it.

Black comedy has a political dimension, usually. You’re satirizing some sort of positions of power or criminality or corruption. But it’s also — I’m trying to think of why it’s an attractive genre now… It definitely has a powerful critical dimension, but it also addresses itself to an audience as an entertainment genre film. There’s a comic side. So it engages an audience in a way that a ticket paying audience can derive the pleasure it expects it’s paid for.

NS: Catharsis?

SK: And entertainment, humor. So it’s a really clever way to make a film, a market designed film that’s also engagé. But also very critical. There are a lot of recent dark Chinese films, and even very serious social work Taiwanese films that are very critical politically and motivated by this powerful sense of critique. But they’re kind of tough on an audience, and they tend to work, at least on the Taiwan side, better as TV documentaries.

In China it’s a way to get around the censors. I just saw The Conformist 冰之下, starring Huang Bo. He’s won some awards for that. The director is Cai Shangjun, it’s his second film. And there’s a whole strain of noir films or black comedies in China now. Which allows directors to talk about corruption and crime in a way that seems safer, because you’re not doing an attack film, a political film. Have a Nice Day 好极了 is a black comedy.

NS: Yeah, I was thinking, too, about Ning Hao’s films, as being kind of the start of some the earlier black comedies that were coming out in China. So Crazy Stone 疯狂石头, and Crazy Racer 疯狂赛车, which I think is kind of how Huang Bo got his start.

SK: Yeah, Ning Hao launched him.

Yangtze Landscape, directed by Xu Xin (China, 2017)

NS: As venues for screening documentary films have been getting more limited, have you seen much crossover from the documentary scene into mainstream filmmaking?

SK: Elements of documentary are certainly more and more welcomed into fiction, like Jia Zhangke, in his film 24 City 二十四城记. There are a lot of films like that in film festivals now. And in China there are even more I think, there’s a really interesting zone. Maybe because, it may be a little glib, but the Chinese reality can’t be captured by reality, you need fiction in order to make true documentary. But the cliché is kind of true, you know?

NS: Kind of like the idea of hyper-realism.

SK: Or surrealist documentaries? So Xu Xin’s Yangtze Landscape has elements of Crosscurrents in it. You have the two actors from Yang Chao’s feature, the male and female leads who occasionally wander in to the documentary. Off in the distance, you have the actors from Crosscurrents, they kind of come in and out of the scene, and the documentary doesn’t mark them, there’s no way to know unless you’ve seen Crosscurrents that you know he’s somehow filming the Crosscurrents shoot. But he uses them, he just mixes them in without marking them as special material.

NS: I remember that was something that really surprised me when I first started watching Jia Zhangke’s films, how he started to blur that line in some of his later movies, not really differentiating whether this is actual documentary or this something that is staged.

SK: There is no line, really. I mean, I think there’s an arbitrary genre line drawn by people who like to classify films. But there is no line. Its all shots cut together, and you always arrange what’s in front of your camera. You chose what to shoot and you cut out what you don’t need.

The Vancouver International Film Festival ran from September 28-October 13, 2017. For more on this topic, see Part I of our interview with Shelly Kraicer.