Ricepaper Magazine’s Poetry Editor Yilin Wang recently conducted this interview with Minh Bui Jones, editor of Mekong Review, an emerging Southeast Asian literary magazine. Questions were also contributed by Ricepaper editors Karla Comanda and William Tham Wai Liang.

Would you please start by describing Mekong Review in a few sentences?

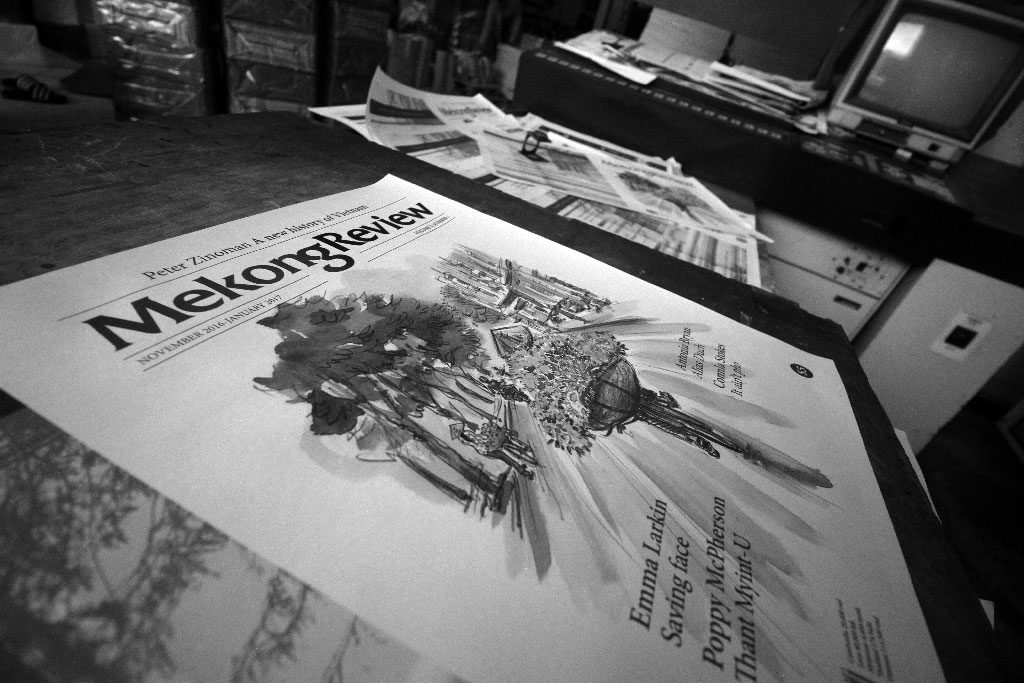

Mekong Review is a quarterly magazine on Southeast Asian literature. Purists would say we stretch the definition of a conventional literary magazine, with our interviews with journalists and bloggers, profiles of artists, the odd piece of reportage and travelogue, along with the traditional fare of book reviews, poetry and fiction.

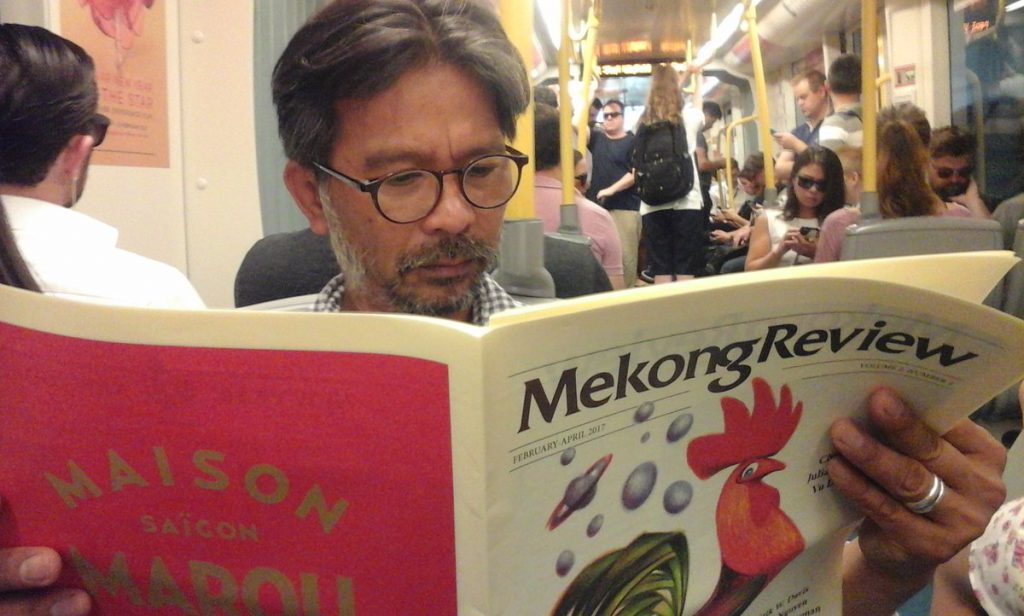

For the moment Mekong Review is based in Sydney, where I live. We’re printed in Penang, Malaysia. Our readers, like our writers, are scattered all over Southeast Asia and the world.

Why did you start Mekong Review?

First, I love magazines. I love the form, its history, its association with political causes and social movements. I especially love little magazines and what they stand for, as a revolt against the status quo.

The idea of a regional literary magazine has been bubbling away in my head for years (I had done a four-page dummy years before the magazine was launched). I’m an avid reader of the London and New York Review of Books and Paris Review, but they’re Anglo-American publications, so they don’t satisfy my craving for books on Asia. In addition, they have that outsider’s angle on the region, that is bent on orientalism and China.

I was getting tired of the narrow confines of a lot of English-language writing on the region. Seemingly everything was yoked to the chariots of Western liberal democracy and all its norms. We were guilty, myself included, of riding roughshod over the cultures which we barely understood. I so wanted to get off my high horse, and to listen to the people who live there, who don’t have a second passport and who have nowhere else to escape to.

Apart from the long-suppressed desire to start such a magazine, there was also my personal predicament. After seven years in Cambodia, my wife and I had decided to return to Sydney. I wanted to create something that would preserve, in magazine form, the memories of my time in that country as well as keeping me tied to that place, that region.

How does geographic distance affect the way Mekong Review covers on-the-ground issues and its relationship with its writers/readers?

Despite the free-floating nature of our operation, we are grounded in the places that we write about. That is to say, most of our contributors live, or have lived, in the cities and countries that they write about. To wit, we get the people on the ground to write about those issues. When that’s not possible, to look to the experts. And when that’s not possible, we wait until we find the right person.

As for our relationship with our readers and writers, I try to do a road trip two or three times a year, visiting as many cities and countries as possible, attending festivals and giving talks. In between, I spread myself on the social media, answering queries and posting news and sweet nothings.

What in your opinion has contributed to the growing group of independent publishing initiatives across Southeast Asia, and how do you see the region’s political climate affecting publishing?

First, it’s difficult to generalise. Secondly, independent publishing comes and goes and it’s hard to identify the reasons for their coming and going. I would suggest technology plays a significant role. When the internet was hailed as the publishing model du jour, you saw a lot of ezines blooming, many of them have withered.

On the question of political climate affecting the publishing culture, again, that’s hard to say. In my experience, Cambodia has been fertile ground for publishing and for journalism for the last 30-odd years. A relatively weak state combined with laissez faire anarchy has certainly contributed to it. But that’s coming to an end now.

What has been some of the main challenges with publishing Mekong Review?

We’re a little magazine, so the main challenge is always money. We’re not supported by any institution or foundation or moneyed angel. We survive on what we produce. Every issue is hard yakka, but it’s getting easier.

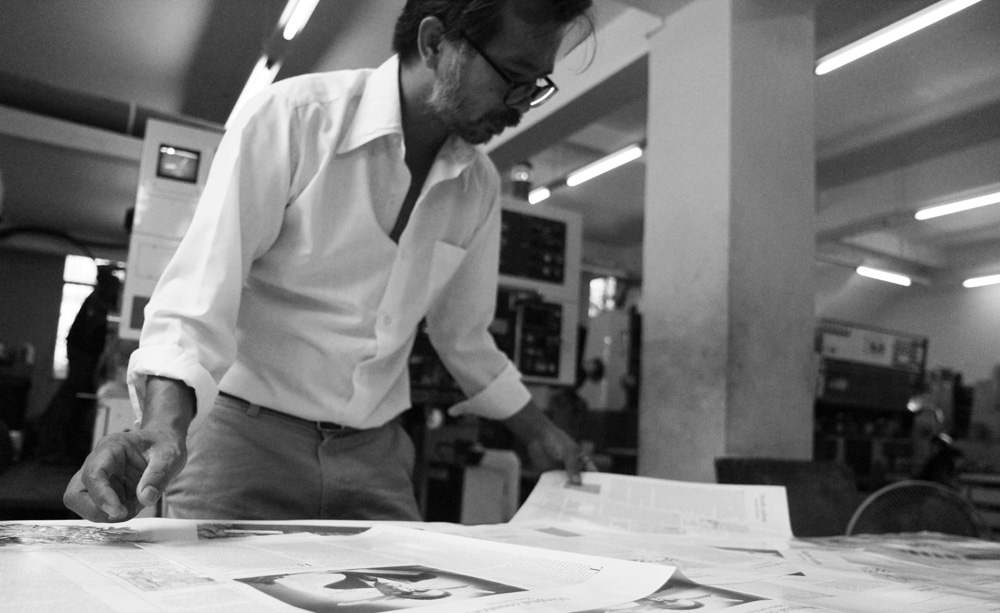

How would you describe the aesthetics of your publication?

It’s minimalist, inconspicuous, quiet. We aspire to a simple, modest elegance. Everything we do is focused on the reading experience. I watch out for anything that might distract the reader from the pleasure of the text. If I run a photo, it’s in B&W, large and prominent. I hate multiple small photos. It looks messy and it dilutes the impact of the photos.

I love working with the paper medium. The constraints of space force you to work harder, I feel, as well as feeding that obsession with shorter headings and tighter editing. There’s no room for self-indulgence. There’s no second chance, so you had better get it right. As a journalist, I feel at home here.

What are your plans for the next few years?

I would like to break into the US, which is the biggest magazine market in the world. That seems key to our long-term survival.

For readers who are interested in reading some writing from Mekong Review, what are some of your favourite pieces you have published?

Ah, that’s easy. Michael Uhl’s essay on the My Lai massacre and Mai Huyen Chi’s re-reading of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American in the current issue; Sebastian Strangio’s great report on the assassination of Kem Ley in Cambodia; Pim Wangtechawat’s whimsical and moving essay on shopping malls in Bangkok; Tillman Miller’s interview with Pulitzer Prize-winner Viet Thanh Nguyen; Penny Edwards beautiful essay on Marguerite Duras; and Thomas Bass’s critical review of Ken Burns’s The Vietnam War, which put us on the map. I have so many favourite pieces.