1942 draws to a close with the Watada family still interned in the abandoned town of Minto, BC, during the beginning of the Japanese Canadian ‘evacuation’. Terry Watada reimagines his father’s experiences based on a diary written during the war years. Translated by Michiko Abe-Kozlowski.

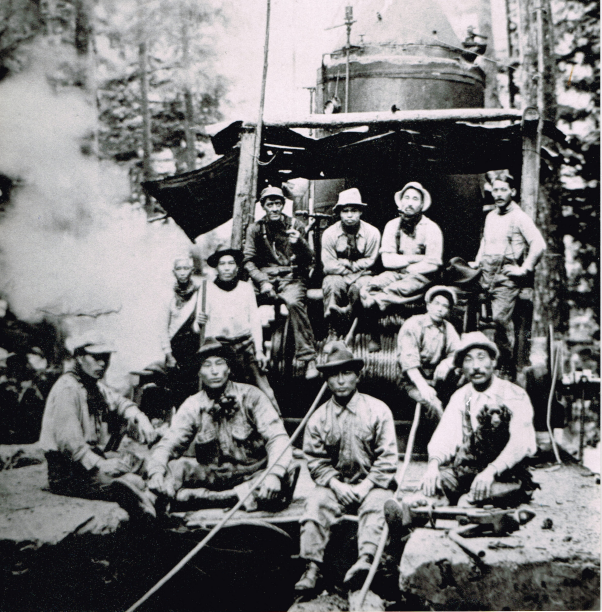

Kagetsu logging camp, circa 1920. Photograph courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

[Front Row, Right to Left]: Terry Watada’s grandfather, his father, and his uncle. The man behind his grandfather is Konishi. The huge machine in the background is a donkey.

Thus, after working eight hours during the day, I had to work at night, too, with the temperature dozens of degrees below zero. Thanks to Shimizu, the work finished at midnight.

“Hey, why don’t we beat Takeuchi up?” Shimizu suggested.

“Well, we will talk to Morii-san to sort it out,” another answered.

“He made fools of us.”

I heard them saying those words after work and wondered what they were talking about. They continued talking behind me, as if they wanted me to hear, “We’ll gang up on him and bury him in the snow”, and so on. It seemed that the guys from Bridge River got mad because Takeuchi, who had been a mere counterman at the Union Fish [ii] shop before the War, was above himself as the boss. He constantly threw a pickerel [iii] at them and talked down to the men all the time. That night, while I was pretending to be asleep, Takeuchi, perhaps worried, got up around 1 or 2 a.m. and wrote a letter. He then asked Evans, who passed by around five in the morning, to take it with him back to Minto.

Thus, after working eight hours during the day, I had to work at night, too, with the temperature dozens of degrees below zero.

The next day, our benefactor Mr. Morii came and somehow settled it. Soon after that, the night shift work was disbanded. There was no bus to return home on Saturday night, so Yoneta and I worked again the next day. I think it was March 1943. Although I didn’t feel it much at the start since I was working, it was bitterly cold. I had a runny nose and wasn’t even able to keep my eyes open and nose clear. Alas, I could only blame the war for this hardship we had to go through!

In April, we were asked to work as high riggers [iv] since the owner [v] had bought a donkey [vi], so with Jikemura-oyaji as a boss we formed a team, including Murakami as a hooktender [vii], Toshio Nishi and Toshiji Nishi as chokermen [viii], and Jiro Iwasa as an engineer. My job was to dislodge the logs from one another while Ichiro Yamashita was to whistle in case of danger. Unfortunately, we were not able to cover the large area because the trees were too short and the donkey was one size too small, so it wouldn’t work with a load of logs as we had hoped. The team was temporarily dissolved. The two Nishis then left the team to move to the East [ix]. I moved with the team from one place to another three times that winter with new chokermen, Cho Kameda and Yoneichi Sakai. We were asked to build a bridge over the river so that logs across the river could be brought in. But what a foolish thing to do – we were to lay out logs over the river without building supporting poles! When we placed the last log, all the other logs collapsed with it.

“I didn’t think it would work,” Kameda admitted.

“The ketō [x] has a lot of nerve”, I thought.

At last, we crossed the ice with the donkey and we piled the logs to haul them. Then Jiro Iwasa left for the East. I took over as engineer next.

When that was finished, we moved to Mission Mountain where we made our own meals. We were all young. Murakami and I were the cooks. Because vegetables were not readily available, one of the dishes we made often was udon [xi] with meat, cabbage and egg. It was kind of fun. At night, we had tea and pancakes. I made big pancake [xii] in a frying pan because it would be too much trouble to make one for each of us. This was an episode which we talked about often for years.

On Sunday, after we completed the work, two cars came to pick us up. When our car was driving down the slope, it slipped at the corner and overturned [xiii]. Fortunately, no one was injured except for a few bumps and scrapes. The car was not too heavy so we were able to lift it up and get on board again. It was very late when we were finally home. We hadn’t even had supper. We only had had oranges, which we took from the Mission Mountain camp. They didn’t fill our stomachs, but we thought ourselves lucky that no one had been hurt. The keto was laughing hard, holding his sides, saying the way I had run away was funny.

Back at the sawmill, we were not able to use the donkey as we tended to be asked to work only in the worst places.

They talked about how someone in a farmhouse aimed a gun at them or how they were treated kindly in another place, and so on.

At the end of September, we took the donkey to Birken [xiv]. I was to climb down that steep mountain road with the donkey, while others were ahead of me. Although I felt terribly uneasy, I managed to turn the curve in the road safely despite fearing for my life and climbed down the mountain road. I took a 9:30 train to Birken the next morning. As soon as I arrived there, I got in a car with others and went to work. I was amazed to see all the trees there were really well-grown.

Once again we were in the camp. Mr. and Mrs. Kuroyama [xv] were our cooks. Although they were a nice couple, I was surprised that they didn’t keep the canteen clean. It was early autumn with frequent rains and fog. Although I was used to it, living apart from my wife and son was very lonely. On the bright side, it was matsutake [mushroom] season and we had it with every meal from morning to night.

One evening on the way back from work, I went up the hill alone away from others only to find a patch of matsutake. In a clearing, I found rows and rows of the meaty and flavourful mushrooms, which no one had ever found before. I bet no Japanese or anyone had ever seen them for thousands of years. Before I knew it, I was exclaiming, “Matsutake da!” So I picked them and put them in a large 50kg sack, which was normally used for rice. It became full in no time.

When I returned to camp with a huge sack full of matsutake, it caused a commotion. The next night, people at the Bridge River camp set out for mushroom picking. Over Saturday and Sunday, they even went inside the area where entry of Japanese Canadians was restricted [xvi]. They each brought in about 35–40 kg of mushrooms that night. They talked about how someone in a farmhouse aimed a gun at them or how they were treated kindly in another place, and so on. I did not want so much for myself so I only searched around the camp together with others, but was able to fill a bag with clean, firm matsutake. This was the first time in my life that I experienced the fun and joy of matsutake picking.

Day after day we had rain and fog. Murakami grew restless feeling lonely and depressed. We eagerly awaited Saturday when we would return to the village. When it was warm, it was all right, but winter came early in Minto, which was located to the far north. The water pipes, which were not well-equipped, easily froze so all the young people in the village would stay out all night pouring water through the pipes while keeping a fire burning to prevent them from freezing. In the midst of all such trouble, we came back to the village in a taxi. Although Mr. Morii welcomed us with a smile, I think he may not have been very happy [xvii].

Matsujiro Watada at the Jikemura logging camp, circa 1940

Shortly after the last entry above, my father was in a horrific truck accident. The vehicle rolled off a mountain road, killing one and severely injuring Dad. He had to be transported to a hospital in Kamloops.

At the same time, my mother was in a Vancouver hospital for a kidney-stone operation. She had a 50/50 chance of survival, aggravated by the fact that the nurses, doctors and nuns held racist attitudes about the Japanese Canadians. They refused to treat her until a Mother Superior intervened on her behalf.

The recoveries were so long and hard that my father had nightmares the rest of his life. He often woke me up with his night screams.

I later learned how much he longed for his wife and how lonely he became because of their situation. The following is a poem he wrote and I translated and re-imagined about their time of separation and period of pain.

To my lonely wife –

Do you see the autumn moon?

I’m broken like you,

taken far away from you,

but I see the same clear sky.

October 1945

In reading the diary translation I learned a great deal about my father and family. He wasn’t lazy, that’s for sure. He always managed to keep working, even in hard times, to earn money so his family could survive. And he loved his wife and son. He was a very caring and devoted parent.

I only wish my brother had read the diary. He then might have realized how much our father loved him, and maybe, just maybe, he wouldn’t have lived a life full of resentment and anger. Hideki died in 2012.

END

(i) Ri is an Japanese measurement of distance. 1-ri is roughly equivalent to 4 km

(ii) A fish store on Powell Street, Vancouver, where local fishermen sold their catch

(iii) An odd insult

(iv) Crew member who climbed to the tops of trees to cut a portion down

(v) Not clear who the owner of the logging company was

(vi) Logging winch

(vii) Man who supervises gathering and hauling of logs

(viii) Men who bind logs to prepare them for hauling

(ix) Probably Alberta

(x) derogatory term for white person

(xi) Japanese noodles

(xii) Dad often made pancakes for us on weekends

(xiii) This foreshadows an incident that affected Dad for the rest of his life

(xiv) Unincorporated community at the head of the Pemberton Pass

(xv) My father told me that Mrs. Kuroyama was a terrible cook. If you were on the second shift, she just poured hot water into the miso soup, swirled it with a ladle and served rather it as rather thin soup. The third shift only got hot water

(xvi) Not sure where but it may have been near the town of Lillooet. Japanese Canadians were restricted to East Lillooet, a field across the river

(xvii) Not sure why he was unhappy. It must have been because he lost all the power and influence he had in Vancouver

Read the first part of Matsujiro Watada’s recollections, as interpreted and translated by his son Terry and Michiko Abe-Kozlowski respectively in 1942.

Terry Watada is a Toronto writer with many publications to his credit including two novels, four poetry collections, two manga, two histories about the Japanese Canadian Buddhist church, and a children’s biography. His latest books are The Three Pleasures (Anvil Press, Vancouver, 2017), a novel about the Japanese Canadian Resistance Movement during WWII, and Nishga Girl (HpF Press and the Toronto NAJC, 2017), an illustrated book about the friendship between Judo Jack Tasaka (a BC fisherman) and Eli Gosnell (a chief of the Nisga’a nation). He is considering a full book version of the diary.

Photographs courtesy of Terry Watada and the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.