Remember the “Comfort Women”

I was 15 and living in Vancouver when I first learned about the ‘comfort women’, a terrible euphemism for tens of thousands of young women sexually enslaved by the Japanese military. My mother had read about it in a Korean newspaper and shared it with me. I was shocked when I couldn’t find any details about their experiences in my Euro-centric history books, like it had never happened.

Years later, I learned from activists and historians in Asia that tens of thousands of women and girls as young as eleven years old were forced into the horrific machinery of rape stations and attacked by up to sixty Japanese soldiers a day. There were more than a thousand of these rape stations in China alone, mostly located at the frontlines of the war. These minors and women were subjected to sexual torture as well as starvation, physical maiming, racial abuse and at times, even death.

The Japanese government and military sanctioned and helped organize the trafficking of women from areas the Japanese considered “racially inferior” for systemic rape, from 1931 until 1945. They called these women “comfort women” because their role was to boost morale and “comfort” the troops.

In 1999, RicePaper allowed me to write about this issue that deeply affects the Asian community – it was one that the mainstream media was not interested yet in covering at the time. Many elder Koreans and Chinese remained bitter towards the Japanese for failing to sincerely apologize for war crimes like the “comfort women” military sex slavery and the massacre of civilians during the Rape of Nanking.

In 2000, after I interviewed 80-year-old survivor Kim Soon-Duk at a press conference in Washington, D.C., her testimony of unspeakable suffering left a deep impression on me. As a teenager, Kim was deceived into thinking she would work in a hospital. But she was forcibly taken to Shanghai to be a sex slave for several years. She asked me to tell the world about what had happened to her.

It cost Kim Soon-Duk and the other women their lives, their futures, their health, their sanity, most survivors couldn’t marry nor bear children due to the damage inflicted on their reproductive system. It cost them everything.

Many elderly women like Kim from Korea, China, the Philippines, Taiwan, and the Netherlands, broke more than fifty years of silence to testify of their sexual enslavement by the Imperial Japanese military. Only a handful are alive today.

I felt compelled to document the voices of survivors in different countries for the next 10 years. All of the women I have spoken with have called on the Japanese government to apologize in a way that would bring healing and dignity. The nation of Japan continues to offer ambiguous regrets that are not sincere official government apologies and has, in the past, spent large sums of money to cover up its involvement in military sex slavery.

I moved to China in 2004 to research further and this led to investigating modern day “comfort women”— sex slavery victims in Asia today. My experience in understanding what happened to the women and girls in the 1930s and 1940s allowed me to see that history was repeating itself. The grave injustice that was never dealt with at the end of World War II has enabled another cycle of sex trafficking to flourish.

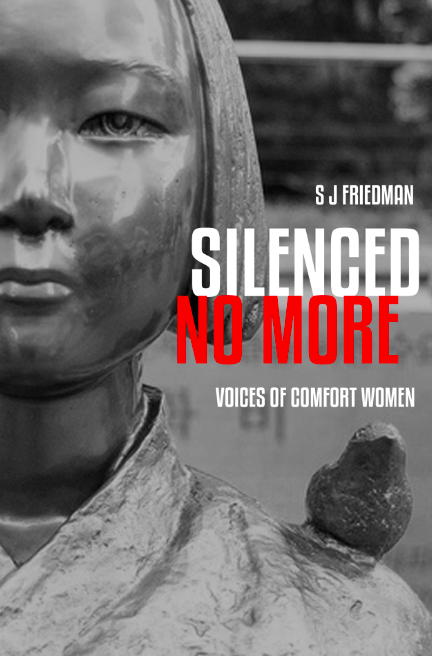

I’ve been a journalist, writer and film producer based in Hong Kong and Beijing since 2004. For me sharing my ‘Silenced No More’ book excerpt with RicePaper is a full circle moment since I first wrote about the issue in 1999. I want to raise more awareness about historical military sex slavery and sex trafficking today. – Sylvia Yu Friedman

**The book’s first edition was published under my pen name, S.J. Friedman. A year ago, I decided to use my name, Sylvia Yu Friedman, on the e-book.

Excerpt from the book, ‘Silenced No More: Voices of Comfort Women’:

Another survivor, Lee Young-Soo, is known as the fashionable grandma and has been described as very smart, a natural politician, warm, and childlike. We met at the home for survivors in Seoul in 2004. Her mother protected her after she returned home after the war. By 2007, Lee had morphed into a type of superstar spokeswoman, touring the United States and speaking before politicians about the resolutions that call on the Japanese government to issue an unequivocal apology and compensation to military sex slaves.

Lee was born in 1928 in Daegu, South Korea. Her impoverished family of nine, including her grandparents, lived in a cramped home. She only had one year of formal education, but her ability to grasp complex information and communicate it in an eloquent way is an innate talent. At the age of fifteen, she was drafted into the “Voluntary Corps.” In the fall of 1944, when she turned sixteen, she was lured away into military sex slavery with her friend Kim Pun-San. On the way to a Taiwanese rape station, she was beaten and tortured.

“It was my first ride on a train, and I vomited. I called for my mother because I was sick. The Japanese soldier came, pulled on my ponytail, and banged my head on the floor. He did this to the other girls too,” she recalled. “And to this day, I still hear a noise ringing in my head. I told the older girls I missed my parents and wanted to go home. I longed to see my mother. That’s what I said. And the Japanese soldiers hit me again because he said I was using Korean. The older women advised me to use actions rather than words.”

Before they were ordered on to the boat, Lee knelt down and desperately prayed to God for help. “As I was praying a Japanese soldier came and kicked me. He followed us all the time. When he kicked me as I was praying and weeping, if my friend hadn’t caught me, I would’ve fallen over into the water,” she said.

On the boat ride to Taiwan, Lee was raped for the first time, and the attacks continued until she could no longer walk properly once she had to disembark from the ship. Lee almost died after a bombing of the underground shelter she and the other women and comfort station proprietor took refuge in. She lost consciousness after she was struck in the head. They were soon moved to another bomb shelter where she was forced to serve soldiers. She caught a venereal disease and was given injections of Serum 606.

Despite the harsh conditions, Lee made it home to her family. She lived with her mother for the rest of her life. Her mother died when Lee was forty-eight years old.

Lee has managed to eke out a living through sales work. She hikes at 6 a.m. every day and maintains a wide circle of friends in different parts of the world. An avid shopper, Lee’s wardrobe is now filled with expensive and beautiful clothing.

When asked if her han (Korean word for indescribable sorrow) has been eased at all, Lee says, “I meet a lot of young people but I can’t ask young people to relieve my han. The Japanese government has to resolve my han. If I have han or nurture it, it ruins my health. So in some ways I don’t want to resolve my han for the younger generation. It is a fighting strength. Some han is released by talking to people or going to protests and seeing many younger people,” she said. “When I speak with young people like you, my han is released a little. I believe it’ll be healed by the younger generation to continue the fight for justice and by the legacy we leave. I don’t think it’ll be released while I’m alive. There has been a hint of relief through the Korean government as they are trying, to some degree, to resolve the redress issue with the Japanese government. But the Japanese government has not done anything to relieve the pain.”

It is clear to see that these elderly women, who have survived, want nothing more than an apology before they die. The survivors are like pine trees in Korea, known as the sonamu. The sonamu is unusually tough and its leaves remain rich green throughout all seasons, through harsh winds, sun and blustery monsoons, sprouting up in impossibly craggy landscapes, and because of its resilience it carries great significance as a national symbol of the Korean people who have endured attacks from invading forces over the centuries. Ever unchanging, the pine’s roots wind deep into the earth and give it strength. The survivors’ strong will to live is like these pine trees. They are dignified, immensely strong, and stately.

The reality is that they may never receive the long-awaited apology from the Japanese government that they want to hear. As they have shared their painful stories with the world and each other, they have also raised global awareness on the horrors of sex trafficking and sexual violence against women and children in war zones, and they have shown the world that these crimes against them must not be tolerated or ignored.

The women’s rights and human rights movement that was birthed out of the struggle for justice for Japanese military sex slaves has had enormous international impact. The peak of this came through the activists’ hard work in promoting the non-binding resolutions that were passed in several countries, including the United States, which called on the nation of Japan to issue a clear apology and take on moral and legal responsibility for its direct involvement in planning and implementing the military sex slavery system.

There must be an awakening to the plight of the suffering through our own sufferings. Before we can see and feel another’s wounds, perhaps we have to be faced with the reality of our own poverty. These women have experienced so much pain. We are at risk of forgetting this is a human rights issue with great political implications in East Asia. There is a need for reconciliation between Japan and her neighbors. We are also at risk of turning a blind eye to the modern day sex trafficking and slavery. We are at risk of ignoring them and callously moving on with our lives.