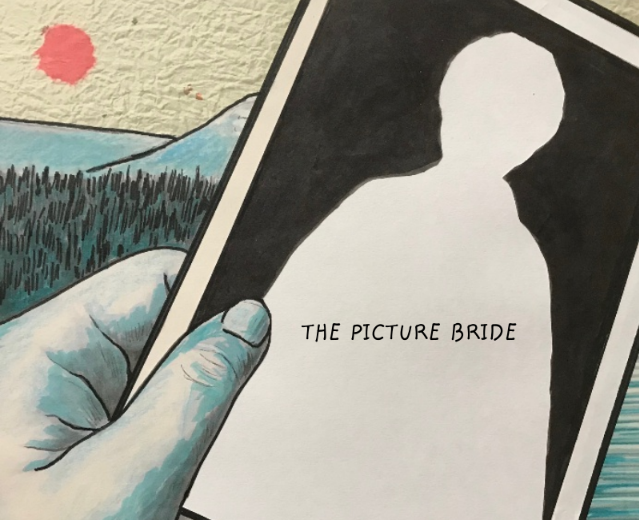

“The Picture Bride” by Lillian Blakey

Nitaro Hamaguchi was born on March 18, 1879 in Kumamoto, Japan. His family was very poor and starving. As the eldest son, his duty was to look after his parents and siblings. He had heard that Canada was a wild, untamed land that needed labourers to build roads and buildings: a land of opportunity. He decided to immigrate to Canada in 1900 so that he could send money to help out the family he left behind on Kyushu. He was only twenty-one.

In those days, people crammed on steamships for months, which were tiny in comparison to today’s liners, to finally arrive in Vancouver, a settlement on British Columbia’s coast. Vancouver was mud and tree stumps, and boardwalks like those in Western movies. There were very few women; life was so harsh that only those who were desperate lived there. There certainly weren’t any Japanese women.

Nitaro had left his ancestral home alone, without friends or family, and wound up thousands of miles away, where just a handful of men spoke Japanese. He was one of the first Japanese pioneers in Canada. He was lonely and worked at odd jobs—clearing the land, building roads, logging and laying tracks for the railroad—from dawn until dusk for seven years before he became a Canadian citizen.

He worked tirelessly to save enough money to buy a fishing boat. He became a salmon fisherman who travelled up and down the coast. He spoke several Aboriginal languages, which he learned from the Aboriginal people. They were the most inviting of all the people he met and they taught him a lot about the dangerous currents and undertows in the ocean which could pull him out to sea. Meanwhile, the city’s predominantly English population had very little to do with him, apart from hiring him as cheap labour.

Vancouver was mud and tree stumps, and boardwalks like those in Western movies. There were very few women; life was so harsh that only those who were desperate lived there.

Nitaro was very lonely so he decided to arrange a marriage with a woman in Japan. Maki Teramoto, was born in his hometown on April 12, 1893. Their families arranged for them to marry through a “go-between,” which was the common practice in those days. Her family was fairly well-off since they were orange growers, but she could never have inherited the business as a woman. Marriage was her only security, but she was getting too old for many men of her class who wanted someone under the age of twenty. If she refused the arranged offer, she would be disowned and left penniless in her small city. After so much difficulty in finding a man of their class, she ended up with a humble fisherman. She had no choice in the decision.

She left via Yokahama and arrived in 1913 as a “picture bride,” a woman who had only seen a picture of a man fourteen years older than her.

She brought with her a set of miniature figures of the Seven Gods of Luck to protect her good fortune and a collection of dolls for the Boys’ Festival, Tango no Sekku, which is celebrated on May 5th. In Japan, this day has been celebrated for over a millennium. Originally, it celebrated boys’ courage and determination in the houses of warriors. Many of the symbols depicted the character of a warrior: chivalry, bravery, and loyalty to the Emperor. Maki carried the dolls with her wherever she went in Canada, as they were all she had to remind her of her home in Japan and her cultural heritage. She brought the Boys’ Festival dolls instead of the dolls for the Girls’ Festival, because she wanted sons. Ironically, all she ever had were daughters.

How could a woman go alone to a country she didn’t know, to marry a man she had never met? She must have been terribly frightened since she couldn’t speak English and didn’t even know if there were any women she could befriend.

Nitaro met her at the dock with a sign that had her name written in Japanese. They were both very shy since they were still strangers, but he was kind to her and took her to his home, a small cabin in a tiny village on the coast, where he kept his boat.

Some English women in the church taught her how to make bread and how to dress in western clothes. Even though she couldn’t speak English, these women made her feel welcome. Since Nitaro was gone for months on fishing expeditions, she would have been lost without them. The women also helped her find a job in the local cannery. They taught her how to get rid of the smell of fish, which clung to her hair and clothes. If she washed herself in cold water instead of hot water, the smell would go away immediately. It was awful to have to wash in icy water, but it would have been worse smelling like salmon all the time. Having to cut off the heads and tails, gutting, scaling and fileting stinky fish all day was very different from her life in Japan where she was a lady and never had to do any menial work. However, money was scarce since both she and Nitaro sent money back to their families in Japan, and she had to contribute as well.

They taught her how to get rid of the smell of fish, which clung to her hair and clothes. If she washed herself in cold water instead of hot water, the smell would go away immediately.

Eunice was born on May 31, 1915 in Bella Coola. She was named by an English nurse. Nitaro and Maki felt that since they were now citizens of a British colony, their children should have English names. They thought her name was spelled “Unis,” but Eunice appeared on her birth certificate. Two other daughters were named after flowers: Rose and Lillie. It was hard for Nitaro, who could not count on sons to help him with the hard work.

Eventually, they moved to Vancouver and Nitaro resumed his fishing business up the coast. One year, he had a partner so they could fish farther out to sea and travel up the coast to make more money. The trip was extremely dangerous since his boat was small, and the sea was very rough in some places. He had to know the tides—if he misjudged the timing, he and his partner could have been swept out to sea. Thankfully, they safely returned to Vancouver Harbour, to Maki’s relief. Most of the time, she complained endlessly about her husband, but that one time, she cooked his favourite foods and was very kind to him.

TO BE CONTINUED

Lillian Michiko Blakey is a third generation Japanese Canadian. She had many works published in her career in education. The largest publication was a language series K–3, Our Wonderful World with Pearson International publishing Inc., the first to offer an anti-bias, inclusive approach to teaching literacy. In 2016, she won the Nikkei Voice Short Story Competition, with Konnichiwa. She is also a professional artist with works in the permanent collections of the Government of Ontario Art Collection and the Nikkei National Museum, B.C. In 2019, her work will be included in an exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum, Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world.