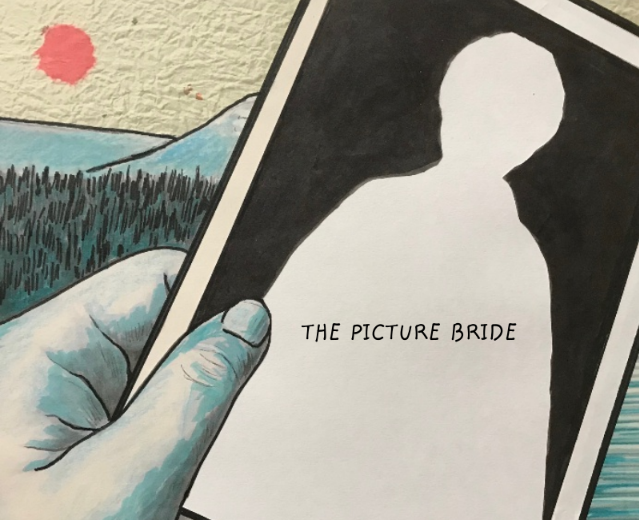

“The Picture Bride” by Lillian Blakey

War was the farthest thing from Maki’s mind even after three years since the war had started in Europe in 1941, as life in Canada had remained peaceful, normal and predictable. People went about their daily activities, raised families and enjoyed their leisure time. The sun rose. The sun set. Night followed day. The seasons followed one another. Year after year….it was unthinkable that the war could come to Canadian soil.

Maki’s daughters were listening to the radio when they heard that Japanese planes were coming to raid the West Coast. Maki would never forget December 7th. It was the worst day of her life. She was stunned and very afraid, not only for her own children, but for her relatives in Japan. The planes never did come as far as Canada, but they did attack Pearl Harbour, the American base in Hawaii. From that day on, life was a horror for Japanese Canadians.

Here is her daughter Eunice’s firsthand account of what it was like to be persecuted systemically by her own government:

“Even though we were Canadians, we were called ‘aliens’ and treated as the enemy. It was awful. Young people like me had never been to Japan. We honoured the British flag, loved Frank Sinatra and danced the foxtrot. It was hard to understand what was happening.

“A curfew from dusk to dawn was imposed and we were not allowed to leave the house after dark. Of course, in the wintertime, it got dark very quickly. Being young people, we found it very difficult to stay home and do nothing. Our friends on our street used to sneak over to our place to play cards with us. Finally, the police became suspicious and parked their cars in front of our house. Our friends had to stay until the police left, which displeased Mother.

“I was twenty-six and married with two children, when war against Japan was declared. The Canadian government forcibly uprooted all Japanese-Canadians from the West Coast. Women and children could go to internment camps and men to road camps in the interior of British Columbia. Alternatively, families could stay together to work on the sugar beet farms in the prairies. My mother was very reluctant to be separated from our father. She wanted our family to be together, so we decided to relocate to Alberta. It’s funny, but they called it an ‘evacuation,’ which typically means saving people from disaster, not forcing them to leave their homes and belongings to go to a dreadful existence.

“Before leaving Vancouver, I sold the furniture, but my father’s boat was confiscated without any compensation. Father had just cleaned and painted his boat for the winter. He had renamed the boat ‘Nancy’ after my first daughter. He was a naturalized Canadian and we were Canadian-born, but we had no rights. They even took away my little Kodak box camera. We were allowed to take only one suitcase for each person. Everything else was left behind. The government said that we could reclaim our things after the war, but that never happened.”

Our friends on our street used to sneak over to our place to play cards with us. Finally, the police became suspicious and parked their cars in front of our house.

Nitaro had lived in Canada for forty-two years, but neither he nor his family had any rights as Canadian citizens. With only the allowance of one suitcase, Maki refused to budge from her home unless they let her take the Boys’ Festival Dolls. The dolls were her last ties to her home in Japan. In the end, she got her way and the dolls went with her.

The family left their Vancouver home without a word of complaint. The Japanese saying “Shikata ga nai,” means “it can’t be helped.” There was not even a single rebellion from the Japanese Canadians whose lives were turned upside down as everyone had to move at least one hundred miles inland. Every single Japanese Canadian honoured the decision of their government’s drastic War Measures Act.

In May 1942, Maki’s family arrived in Lethbridge, Alberta by train and were escorted like convicts by the RCMP. Their clothes were inappropriate for the harsh Alberta winters. They were city people with city clothes. Everyone was fingerprinted and had to show their identification cards everywhere they went. The experience was bewildering. They were rejected by their own country and no one spoke up for them, neither their Caucasian neighbours, nor their friends.

Maki’s family was the last to be chosen, since most of the adults were women and Nitaro was too old for farm work. Eunice’s husband was the only young male. The farmers who were assigned to take the family to work on their farms arrived to claim them at the station.

Maki was extremely upset. They were taken to a farm outside Coaldale. Their “house” was a chicken coop, which was extremely cramped for the nine of them—Eunice, her husband, her three children, Nitaro and Maki, Rose and Lillie. They barely had room to cook, eat, and sleep. The room was filthy with chicken droppings. The window was broken and orange crate slats were hastily nailed over the opening. And it had an old, broken-down cardboard screen door. Maki hung a comforter to keep out the cold air, but it was useless.

The coal stove was kept going night and day to keep them from freezing, but they were always cold. They had come from very moderate winters in Vancouver to the bitter prairie winters, which often dipped to thirty or forty degrees below freezing. The farmers were supposed to provide them with proper housing and bedding, but this farmer provided neither. The “bedding” consisted of sacks filled with scratchy straw. That first winter was excruciating.

In summer, it was unbearable inside. There were hundreds of flies everywhere, in their hair, on their faces, and all over the walls. They sprayed DDT to no avail. Many in the family would develop cancer after leaving Alberta.

The farmers who were assigned to take the family to work on their farms arrived to claim them at the station and the family was split up.

You couldn’t imagine more backbreaking work than on a sugar-beet farm. Maki and her family rose at the crack of dawn to go out to the field to thin, weed, hoe, and finally top beet plants.

The beets were planted in thick rows about three feet apart and when the seedlings were about an inch high, they thinned them out to single plants about a foot apart, all the way down the rows. They worked until dusk when they could no longer see what they were doing. When they returned home, they did all of their chores—cooking, washing, preparing food for the next day, and putting the children to bed. All they did was work.

A few weeks after the thinning was finished, the farmer cultivated the ground with his horses, and they would go over the whole field, hoeing and pulling out the weeds. If there was a drought, the farmer irrigated the field with water diverted from a canal.

Topping started around the end of September. The farmer used his horses again to pull a plough to loosen the soil around the beets. It was the family’s job to pull the beets out of the ground. They took two beets, one in each hand, and banged them together to shake off the soil. Then they cut the tops off and threw the beets into piles as they worked along.

Sometimes the soil was wet and it was very heavy lifting the beets up. Since it was very sticky gumbo soil, and each beet weighed about fifteen pounds when caked with mud. The work was daunting. Even when the weather was awful, they had to keep on working until they had finished the whole twenty acres before winter set in. There were times when the beets that they pulled out of the ground were frozen solid.

They worked alongside German prisoners of war, who were very pleasant young men. The girls found out that the Germans could understand French, so they laughed together and had the best time they could. However, the soldiers guarding them with rifles reported the Germans, and as a result they were not allowed out for several days. There was a barbed wire fence around the field. Were they to keep the cows out or to keep Maki’s family and the Germans in?

The girls found out that the Germans could understand French, so they laughed together and had the best time they could.

When the war finally ended, our family was split apart. Eunice’s husband was not a naturalized Canadian so he was deported in 1946. He was just about to become a citizen when war with Japan broke out and the government prevented any more Japanese from gaining citizenship. Eunice and her children went with him.

They were herded like cattle onto the American transport ship Marine Angel, which took them to Japan, where they were stranded for twelve years before they could return to the country where they were born. There were none of the comforts of a passenger liner. All of the deported Japanese Canadians slept on the cold metal floor of a huge space, along with the tanks, jeeps and other military vehicles.

For Eunice and her children, being sent to a war-torn and defeated foreign land, was a dreadful experience as the Japanese treated them as though they were “the enemy.” Eunice’s children were taunted by Japanese children through angry outbursts.

Why aren’t your eyes blue? Go back to America! We don’t want you here.

Eunice got a job as interpreter for the American army stationed in Japan. The GIs were good to her, giving her children chocolate bars and special treats, but that just made the Japanese children even more unable to accept them as friends. Japan was devastated after the war and the people were starving. The Japanese felt that Eunice and her family were traitors.

In 1947, Nitaro, Maki, and Rose returned to Japan as well, their dreams shattered. Their daughter, Lillie remained in Canada with her husband. Nitaro never saw her again, for he died in Japan. Maki, Eunice and her four children were finally allowed to return to Canada in 1962 to get better medical care for Rose, who had contracted Tuberculosis. But it was too late and Rose died at the young age of 39. They brought Nitaro’s ashes, which were buried on Canadian soil with his daughter Rose.

For Maki, it was still home.

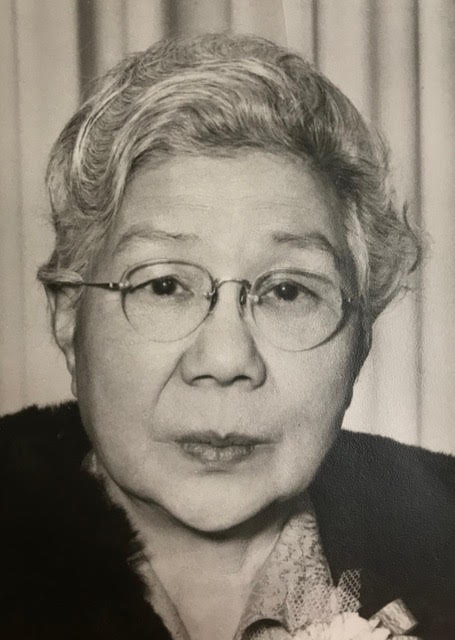

Maki: 1968, upon her return to Vancouver from Japan

Lillian Michiko Blakey is a third generation Japanese Canadian. She had many works published in her career in education. The largest publication was a language series K–3, Our Wonderful World with Pearson International publishing Inc., the first to offer an anti-bias, inclusive approach to teaching literacy. In 2016, she won the Nikkei Voice Short Story Competition, with Konnichiwa. She is also a professional artist with works in the permanent collections of the Government of Ontario Art Collection and the Nikkei National Museum, B.C. In 2019, her work will be included in an exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum, Being Japanese Canadian.