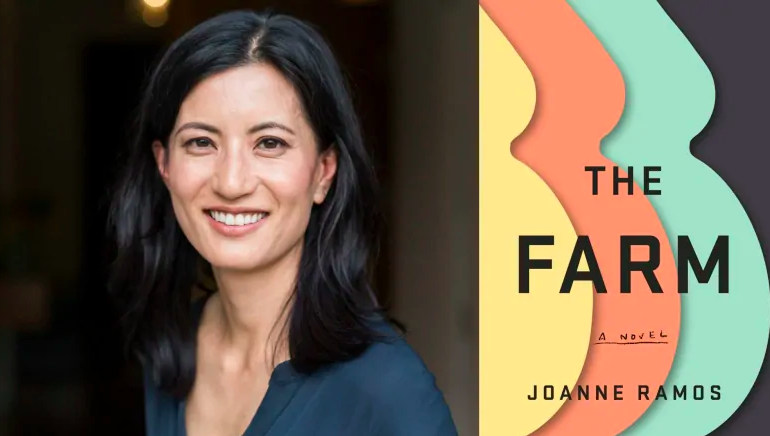

Joanne Ramos is a mother, The Economist staff writer, and now the author of The Farm. She is one of the featured authors in Vancouver Writers Fest this October 21st to 27th.

The Farm tackles with a vision of the near-near future where pregnancies are outsourced into willing surrogates who carry the offspring of the 1% for a fee, but what is sought after are the hefty bonuses upon successful delivery. The central character, Jane, a single mother just out of a job reluctantly accepts the role for the lucrative reward to give her child a brighter future.

However, as it is revealed that the baby Jane carries holds a lot of stakes for the owners and higher-ups that run the surrogacy company, Jane’s body progressively becomes the ante for a harrowing late capitalist game where the facilitators reap all the rewards, and the surrogates take all the risks.

Vincent Ternida (VT): Do you consider yourself a diasporic author with a thriller flavor or a thriller novelist with a diasporic flavor?

Joanne Ramos (JR): I don’t consider myself either, honestly. I’ve loved writing stories since I was a child—but I always saw writing as something I did on the side, to sate a compulsion. As a young adult—in college and afterwards—I was focused on paying down my substantial college debts and being “practical”. I kept writing, because writing is how I digest the world—journals, long emails-cum-essays to friends—but I stopped writing fiction.

It wasn’t until my forties that I committed to writing the novel I’d always hoped to write. I definitely did not set out to write a thriller, nor even a dystopian novel. I was interested in exploring the ideas that had consumed me for most of my adult life. These ideas were rooted in the people I’d come to know, and my own experiences, as a Filipina immigrant to Wisconsin, a financial-aid student at Princeton University, a woman in the male-dominated world of high finance, and a mother of three in an era when parents believe their job is to give their kids “the best” of everything—and when enormous wealth inequality means some children enjoy a vast head start in life from birth.

Of course, ideas don’t make a novel. In fact, they can make a very bad novel if they don’t have the right story to bring them to life. This was the challenge: to find a compelling, engaging narrative that would draw readers, maybe even unwittingly, into the dialogue I’d been having with myself for so long.

About a year and a half into writing daily in the dark, I read a short article in the Wall Street Journal about a surrogacy facility in India. This was all I needed: the what ifs started bubbling, and The Farm began to take shape. There was no outline, no goal of writing a certain genre of book, whether thriller or dystopian or diasporic. I wrote my way into the characters and the story.

VT: What pushed you towards the direction of literary writing from a journalistic background? When was the point where you said — “now is the time to make the jump from journalism to fiction”?

JR: As I mentioned before, I’ve loved writing since I was a child. I remember getting my first diary for my First Communion when I was six, and I’ve kept one, off and on, ever since. Breaking into journalism after a career in finance wasn’t easy. I had no press clippings to prove my worth. What I had was knowledge, gleaned from my years working in banking and investing, about business and money, and I used this to get an internship and then a staff position at The Economist (this process, by the way, took years).

I learned a lot during my time at The Economist: how to write clearly and sparely; about markets—when they work and when they fail—and that there is no simple way to create a productive and just economy. And yet, my love remained writing stories.

I hadn’t worked on the writing staff of The Economist for years when I decided I was going to write a book. I’d taken a break from the workforce with my third child, and I was thinking a lot about the nannies and baby nurses and housekeepers I’d befriended during my days at the park and on playdates. Many of these women—and they were all women—were Filipinas, like me. Most of them were mothers. Some of them had left their children back home in Manila or elsewhere and supported them by helping to raise other people’s (much more privileged) kids in New York. Often, my new Filipina friends would praise me—for being the Filipina who “made it”, for showing them that the “American Dream” is real. And yet, so much of my “success” relative to theirs was due not to merit but to luck and happenstance.

I could have written a non-fiction book about domestic workers or the Filipina diaspora. It honestly never occurred to me to do so. I wanted to write a story. I believe that in an era when most of us approach conversations/debates armed with our opinions and certitudes, fiction is uniquely “disarming”. Because it is “made up”, a reader approaches fiction with an openness she might not bring to a non-fiction book or even a memoir. Maybe this openness is because, as children, many of us were told stories at bedtime and in school. Whatever the reason, I think the openness with which we open a novel is an opportunity: to shine a light. To bring in a new perspective.

VT: Regarding the point of view characters in The Farm, they’re written with so much humanity that even the most deplorable antagonists still feel fully realized and I find myself rooting and agreeing with them in the end. How much of the character creation are based from personal relationships/amalgamations of real humans?

JR: The characters in The Farm are fictional, and they were made-up in my head. That said, we are all products of our environments, and so my characters are inevitably rooted in my experiences, observations, and the stories I’ve heard about or read.

I can relate to all four of my narrators in one way or another. I felt lost in my life, like Reagan. I was ambitious like Mae in my young adulthood, and I know many people who are like her: people who are wrapped up in their bubble, so focused on their own well-being, and that of their family and friends, that they don’t really see people outside of their orbit. That doesn’t make them evil. But I do think our system, any system, is propagated in large part because of those who don’t notice, don’t take time to notice.

As for Jane and Ate, well, I’m a Filipina and a mother, too. And I’ve gotten to know Filipinas of all stripes—domestic workers, doctors, mothers, illegal and legal immigrants—both in my childhood, because our town was near my father’s family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where there was a small but tight Filipino community, and later in New York.

I do feel like I’ve straddled a lot of worlds in my life, which has allowed me to get to know different kinds of people. I see blindness on both sides of so many divides. This isn’t a matter of villains or saints, but humans who are blinkered and flawed, and a failure on the part of many of us to truly see the “other”. I suppose this is the reason I worked so hard to make each of my narrators real and complex rather than boxing them up in easy labels: “bad” or “good”, “rich and selfish” or “poor and soulful”. I think the world, and we humans, are more complicated than this.

VT: The Farm is compared to A Handmaid’s Tale and personally I felt it reads like an extended Black Mirror episode. With regard to world building, what made you choose the time in the near-near-future instead of further in the time or completely set right now in 2019?

JR: The world of The Farm is meant to be our world pushed forward just a few inches. Plausibility was crucial. I didn’t want to create a world so far ahead of ours that the reader could dismiss it as “sci fi” or highly improbable. I wanted the world to be our world, heightened. I hoped that in doing this, the reader would get some distance from our current state—because with distance, and the perspective that distance affords, we’re often able to see even commonplace things in a new light.

VT: You mentioned in an interview with The Guardian that instead of “writing what you know”, you’re writing “what you’re obsessed about”. What were the challenges in writing a mainstream thriller as your debut novel? You mentioned writing short stories about the main characters in The Farm as well. Did writing those short stories build up to your novel?

JR: The biggest challenge for me in writing The Farm was believing I could do it. I’d dreamt of writing a book for so long. Taking the plunge in my forties—truly committing to the day-in, day-out process and discipline and craft of writing—was pretty scary. You don’t sell a proposal at the outset, as you do with a non-fiction proposal. You write the entire book—years of your life!—in the hope that someone, someday, might want to read it. What got me through the first year and a half, those many months before I had the idea for The Farm and was writing blindly, persistence, and faith—and a husband and kids who believed in the book even before there was a good idea for the book.

As for the short stories and “first chapters” I wrote during the many months before The Farm truly began to take shape, almost none of them ended up in the book directly. But they helped. Those stories made me think hard on my ideas, and they made me “stack up the pages”, as Ann Patchett says. Writing is a craft before it can be an art, and I was learning by doing. There was one flash fiction piece I wrote about a young, single mother who leaves her newborn baby at home to take a baby-nurse job. The character in that piece was the forerunner for Jane.

Vincent Ternida is a screenwriter, filmmaker and author. He was a finalist for Writer’s Guild Canada’s Diverse Screenwriters West and a second rounder for Austin Film Festival’s screenplay competition in 2013. Ternida’s first novel, The Seven Muses of Harry Salcedo, was published by Asian Canadian Writer’s Workshop. His short story Not All Bears Drink Mead will appear in Immersions: A Speculative Fiction Anthology, which will be released later this year.