Author CE Gatchalian

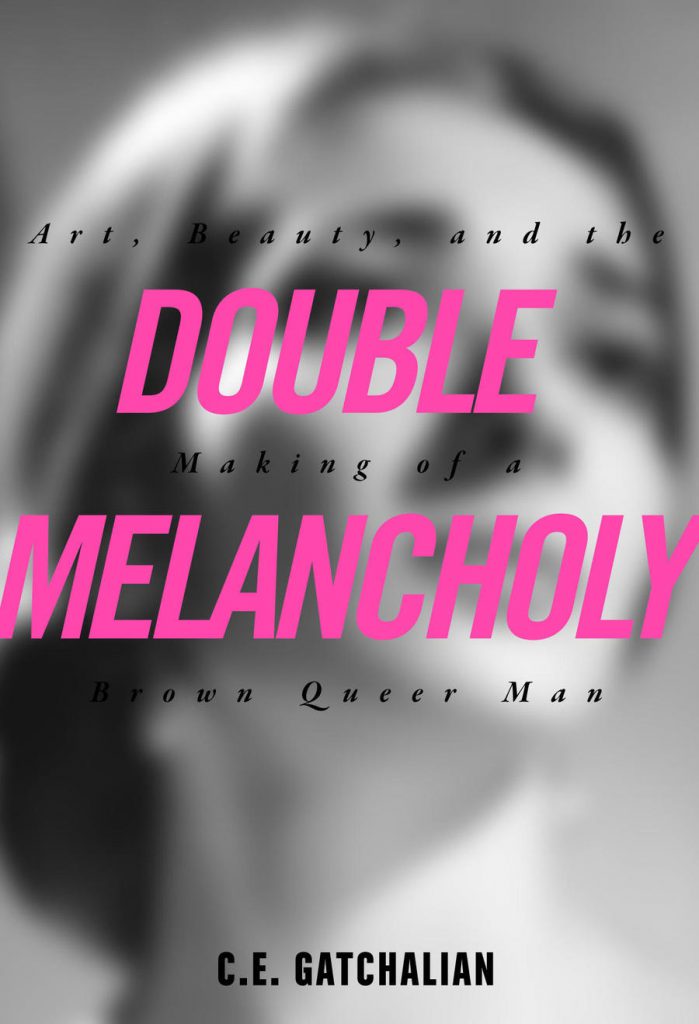

The rain continued in Vancouver, crescendoing into a mini-tempest and I was glad that my next interview would be in a warm, solid venue, with cool refreshments and upbeat piped-in music. C. E. Gatchalian is currently in the middle of promoting his memoir and essay collection Double Melancholy: Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man throughout North America. Featured in Literasian back in September, I had the opportunity to introduce Chris in his discussion of writing life into art.

Chris was able to spare some moments from his busy schedule of being in academia, an author, and an artist to discuss Double Melancholy and the themes surrounding the book in the next couple of hours. As a cisgender straight Filipinx man, we intersected in what he called The Melancholy of Being Brown and we discussed topics centered on publishing, decolonization, and the topic of being Filipinx in a dominantly white landscape.

The Melancholy of Being Brown

Vincent Ternida (VT): To start things off, I’m straight so I have a single melancholy. (laughs) I gravitated towards the themes of unbelonging and the in-between. Could you comment on the concept of the melancholy of being brown?

Chris Gatchalian (CG): As a second generation Filipinx-Canadian, I speak English like a local, and culturally and in the way I move in the world, I’m more Canadian than Filipinx. Still, for obvious reasons, I don’t exactly belong with the white majority. Being in theatre and literature, the majority of people I’ve worked with, and the people in charge, are white. Up until pretty recently, when the climate shifted and it became more acceptable to talk openly about issues of race, my Filipinxness was never discussed. I’m sure the intention behind that strategy was good: in talking to white people, most are conditioned to believe that to talk about or even mention race is itself racist. But by not talking about race and taking a “colour-blind” approach, it turns race into something unmentionable, like a disease. Why should one be blind to my ethnicity the colour of my skin? Why erase an obvious part of my reality and identity? Why not embrace complexity, texture and diversity instead of whitewashing everything under the rubric of “color-blindedness”?

As a second generation Filipinx-Canadian, I acknowledge my privilege. There are circles that I can access that a non-local brown person who speaks with an “accent” may not be able to access. There’s a certain security and safety white people may feel working with me. I’m less threatening, less “Other.”

I initially identified more strongly as a queer person than a racialized person. Growing up in super-diverse Vancouver, most of the schools I went to were mostly racialized people. I never felt necessarily bullied, or marginalized, or “otherized” because of the color of my skin. But I was always marginalized because of my sexuality. It wasn’t until I came out, it wasn’t until I was working professionally in theater, that I actually started feeling marginalized as a result of my race. Because the queer circles I travelled in, and also the professional circles I travelled in, were made up mostly of white people. While no one ever said anything overtly racist, I would get these questions like, “Oh where are you from? No, where are you really from?”

Narrative Voice and Decolonization

VT: Did that concept of Otherness inspire the three distinct narrative voices in your work?

CG: In Double Melancholy, the fragmentation of the narrative voice embodies the process of decolonization. I have a very divided self as you can see, being brown and queer, and these multiple voices are always in debate. I felt that to write a book with one narrative voice would not be faithful to my reality.

When I initially decided to write this book of interconnected essays, the conception of three voices was there from the beginning. I didn’t want to write it in a conventional manner. It was going to be about decolonization, to show them fragmentation, and it was present from the start. I had to rework my oldest essay about Maria Callas to embody the fragmentation as I had described. I wrote that essay way back in 2010. Back then I wasn’t in that headspace.

My process of decolonization has intensified in the last four to five years. A lot of this learning happened while I was running The Frank Theatre Company, Vancouver’s professional LGBTQI+ theatre company. The queer community is so diverse. It’s not a monolithic community, we all have very different interests and as such we don’t often agree with one another on a lot of things.

I was constantly confronted with Otherness. I was confronted with the reality that there is no one true definitive narrative. While working at The Frank, there were many attitudes and assumptions that I took for granted and didn’t bother to question. It was in working with trans people, queer women, queers with disabilities, and the diverse folk in the LGBTQI+ community– in having these difficult conversations, I began to question things I took for granted. For example: I noticed that, in a professional context, I was sometimes inexplicably excluded from certain events I would have liked to have been included in. It’s like, I’m an artist with some standing in the community, why wasn’t I invited to x, y and z? Looking back, it dawned on me that those who were invited and included were virtually all white. Ironically, if I didn’t have conversations with people who didn’t have the same power and influence and privilege as myself, I wouldn’t have realized my own lack of power and privilege on certain grounds.

There’s this illusion in the queer community that everyone is so accepted and nobody discriminates, but that’s simply not true. Even within the queer community, there’s white supremacy.

In my book I spoke about an artist who I really admire and fought for to do a reading of my play. When I met them, the first thing they said to me was, “I was expecting a white person.” I was so hungry for approval from the people who have power, and the people who had power were almost always white. In the moment – and this is an indicator of just how colonized I was — I wasn’t offended. I was just so glad to have this artists’ backing and the fact that they actually were interested enough in my work to do the reading. That’s all I cared about. It wasn’t until later that it landed with me just how offensive their question was. I’m not interested in shaming individuals. I’m not that interested in calling out individual people out for particular racist incidents they may have unwittingly taken part in. It’s more about critically scrutinizing the system. I don’t think that the artist I just mentioned is a bad person. I don’t think they did what they did from a place of malice. Rather, I would say they did it from a place of privilege. The truth is, if you’re in a position of privilege, you’re often not mindful. I’m in that position as well as a cisgender, able-bodied man. There are many things that I don’t have to worry about that women and trans folks and people with disabilities worry about all the time.

The Future of Double Melancholy

The Future of Double Melancholy

VT: On a lighter note, so much of Double Melancholy is about the art and artists that have impacted you and your life. Are there any artists that you wanted to write about that didn’t make the cut?

CG: I was going to write a chapter about Billie Holiday, but I didn’t. There’s already a chapter about one singer, Maria Callas, and there’s a chapter about African-American writers and thinkers that have influenced my art and life. I’ll probably write about Billie eventually, in a future book. Had I had a bit more time to write Double Melancholy, I would probably have included a whole chapter on Jose Rizal, although I do mention him in the book’s final chapter. My journey with my Filipinx identity is a huge, ongoing project. I feel this will occupy a big part of my work as an artist going forward. And not just as an artist, but as a human being as well.

Here’s an interesting observation, and this is just my experience: queer Filipinx men that I’ve met and been involved with intimately — queer Filipinx men who were born and raised in the Philippines, and came to Canada as adults – I have noticed that they carry themselves with a level of confidence and self-assurance that I don’t necessarily see as readily in queer Filipinx men who were born and raised here – including myself, especially when I was younger! It’s not that queer Filipinx men from the Philippines don’t struggle with colonization – of course they do – but at least in the Philippines, they’re confronted daily with role models who physically look like them, have the same colour skin – role models outside of their immediate families, people in positions of power. That’s my rationale for the difference.

VT: I feel like the last chapter of the book is a collection of thoughts. You wanted to explore them but you didn’t have time. A prelude to an afterword.

CG: Again, I didn’t want to end the book with an ending ending – that would have been too colonial. (laughs.) It may have been the end of the book, but not of my journey. That journey has just begun.

Double Melancholy: Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man is out now at your local and independent book sellers. For more of C.E. Gatchalian’s book tour, catch him in Ottawa November 21st and at the Naked Heart Festival November 22-24 in Toronto.

Vincent Ternida’s works have appeared on Ricepaper Magazine, Dark Helix Press, and was long listed for the CBC Short Fiction Prize. The Seven Muses of Harry Salcedo is Ternida’s first novella. He has a collection of short stories in development, adapting his novella into a screenplay, and interviews other writers for fun and profit. He lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.