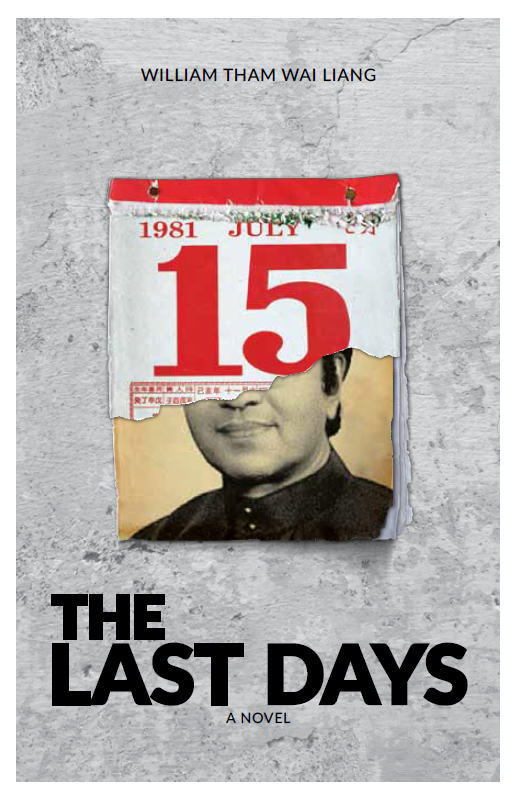

Author William Tham of the “The Last Days”

Juxtaposing Pulp Thriller and Character Introspection

Following up his debut novel, Kings of Petaling Street, former Senior Editor of Ricepaper William Tham’s forthcoming sophomore piece The Last Days moves away from a noir thriller to an introspective political drama.

In a chance meeting, an aging communist revolutionary encounters a mysterious former activist; of who he imparts his exploits. On the onset, a relentless assassin pursues said revolutionary in a final grudge mission. Rounding up the motley crew is a forlorn publication officer who receives a lead on a story from an elusive former lover about the whereabouts of the mysterious activist. State secrets, unrequited affairs, and personal obsessions cross at an explosive tesseract as Kuala Lumpur in 1981 serve as a stage for four disparate forces meeting at the threshold of a new political dynasty coming from a series of tumultuous unrest that besieged the nation.

I corresponded with William on this new project while on his sojourn to Malaysia. This brief interview gives insight to his intriguing web of Malaysian politics, history, and stylistic choices about the world behind his new book.

Vincent Ternida (VT): The Last Days reminds me of a combination of your works I’ve read in the past. Kings of Petaling Street and yet to be published Lost Voices Record come to mind. In a previous conversation, you said you’ve worked on this piece since 2010. How has it evolved with the other long form pieces being created along the way?

William Tham (WT): The journey of The Last Days has been one of fits and starts. It started out as a series of outlines for a very conventional colonial-era novel about the Malayan Communist Party, and how it was eventually forced underground into a strange conflict that took decades to come to a halt. It has very little to do with Kings of Petaling Street, although both manuscripts emerged from the primordial soup of pulp fiction elements that I was interested in between 2013 and 2015.

The Communist Emergency era had been written about endlessly, and it was starting to feel stale. I reimagined my ideas as a short story, following a lone communist agent trapped in Kuala Lumpur instead of standard plots of jungle fighting and political dogma. Later on, I veered away from overtly pulp elements, so The Last Days actually represents a transition between the blood-soaked elements of Kings of Petaling Street and more restrained works such as Lost Voices Record, which in turn was inspired by the 1980s setting of this book.

VT: There’s a level of longing found in your pieces. While the action-packed, the characters find time to slow down and think about their decisions. Ironically, their moments with other characters appear self-centered, losing out on the precious moments spent. Is this how you see a human connection— a series of transient encounters where the best moments are really recollections from a memory once taken for granted?

WT: In many ways, we are the sum of our missed connections. When I come to think of it, a lot of my formative experiences were not really connections at all, rather, they were thoughts of people whom I missed, who had gone on separate tracks, like trains diverted on to spur lines. I would be caught up in the possibilities that could have been and held on to old memories that locked me to our past more tightly then they should have.

In the context of the book, all my main characters are all trapped by their past, in some way or another, lacking the courage to move on. Dain, in particular, is the character that I relate to the most—he can easily uproot himself, switching from one city to another, but all the while he is unable and perhaps unwilling to really let go and move on, thus missing out on his present.

VT: Your chapters represent the waxing and waning of the moon. Is this because the lunar cycle is a common important intersection of the Malaysian Chinese and the Malay Islamic Majority? Are you trying to critique that human notion that a country’s cultures and traditions are quite common but we’re still disparate and fight over the way we interpret philosophical and cultural differences or is it merely a motif?

WT: The waxing and waning of the moon is one of the many cultural motifs (Malay-Islamic and Chinese) underpinning the book, and are very present in Malaysian society to this day. I wish I could have inserted more motifs from the rest of Malaysia’s cultural makeup, but I was unsure how to do so respectfully. I inserted these motifs with the intention of capturing, on a subtle stylistic level, the country’s mixed-up heritage, and how the past continues to influence us today.

While the initial spark of astrological/astronomical motifs came from Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, I noticed, with certain amazement, that Dr. Mahathir first took office during the full moon of July 1981—the moon is a tremendously significant symbol in many ways, more than I am qualified to talk about. Its cycles also represent the cyclic nature of Malaysian society, perhaps hinting at a sense of fatalism, that we are not in any way masters of our fate. Malaysia may look relatively secular (albeit with an increasingly religious bent), but deep down a lot of old cultural motifs are still at work—for example, elements of the wayang kulit—shadow puppet theatre—seem to show up in contemporary political narratives.

Other cultural motifs underpin the entire book, in particular, the number four. A significant number in Malay-Islamic tradition, yet distrusted by the Chinese. The book contains four parts—here I drew inspiration from Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet and Mouly Surya’s Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts. Yet within this construction are eight sub-chapters, with eight of course being significant in Chinese culture. I’ll leave the interpretation up to the reader!

VT: Student protests and activism is a major set-piece in your novel. The timing is eerie that the Hong Kong protests are currently happening defending democracy while there’s a juxtaposition with the communist protests in ‘80s. I’m not sure about the timing of your book’s proofing and publishing, but were you making the juxtaposition or just a coincidence?

WT: It would be useful here, to provide a bit of context regarding Malaysian politics. Any association with communism, ever since the Party went underground in 1948, has always been used as a way to tar opposition to the ruling power. The same logic applies in Indonesia. From the removal of leftist elements within the dominant UMNO ruling party (hence turning it into a vehicle for the feudal-conservative elite) and the strange period with the Islamist party had more in common with the socialists. The narrative kept being deployed up until the late Communist Leader Chin Peng laid down arms in 1989, at the Thai resort town of Had Yai.

The spectre haunting the characters in 1981 is less that of Communism but more of Mahathirism: a focus on heavy industry, rampant capitalism and the shredding and forgetting of the past. I grew up entirely in Mahathir’s shadow, and by then the roots of the past had been so sharply severed that it was difficult to view the past for what it actually was—richer and more remarkable than the staid narratives fed to us in school and through the media.

I did not set out to create an intentional juxtaposition—in fact I actually see more similarities than differences between politics then and now, mostly in terms of the artificial divisions between the political left and right and the presence of authoritarian leaders, or at least leaders with authoritarian tendencies. Returning to the Malaysian context, the world of 1981 looks almost the same as 2020—the same Prime Minister is in power again, and the Prime Minister-in-waiting is still the same chameleonic Anwar Ibrahim.

For all of Mahathir’s faults he did smash the stranglehold of the feudal elite on power when he took over as Prime Minister—although the aristocrats never really relinquished all their power.

VT: You seem to romanticize this time period.

WT: My interest is specifically the transition between the Seventies and the Eighties: that liminal period when idealism gave way to rampant consumerism. The politics of the Seventies eventually became much less charged than the Sixties, plus that was after the fallout of some shattering events in the Nusantara region—the fraught Independence of Singapore, the massacre of the political left and the rise of fascist elements in Suharto-era Indonesia (captured in the film Gie) and the race riots in Kuala Lumpur in 1969.

In a way the end of the Seventies felt like a strange vacuum that was quickly replaced with neoliberalism, and with that comes the excesses and inequality of the world that we have today. I wanted to explore this lost period of idealism further. In terms of fashion and films, music and popular culture…the Seventies were stylish as hell and I could not help but keep referencing those elements.

The Last Days will be released by Clarity Publishing on February 2020. Watch for more of William’s pieces in the future!

Vincent Ternida’s pieces have appeared on Ricepaper Magazine, The Ormsby Review, and Rabble. His short story Elevator Lady was long listed for the CBC Short Fiction Prize. The Seven Muses of Harry Salcedo is Ternida’s first novella. He has a collection of short stories in development. He lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.