Excerpts from Reimagining ChinaTOwn: Speculative Fiction Stories from Toronto’s Chinatown(s) in 2050. (Preface by Linda Zhang)

Reimagining ChinaTOwn: Speculative Fiction Stories from Toronto’s

Chinatown(s) in 2050

What would it look like for Chinatown to thrive instead of just survive? Who holds the right to decide how Chinatown’s future is shaped? “Reimagining ChinaTOwn” is an anthology of short stories which collectively reimagines the world around us. Through speculative fiction set in Toronto’s Chinatowns in 2050, authors envision Chinatown anew, creating radically more generous and expansive worlds than the present. As an anthology, “Reimagining ChinaTOwn” embodies a visionary act of resistance against state-sanctioned narratives by elevating community narratives that exist beyond Toronto’s official heritage definition of its Chinatown neighbourhoods. Each story explores a personal relationship to Chinatown in the aftermath of COVID-19. This anthology began as a writing workshop presented in partnership with Myseum of Toronto in April 2020. Through storytelling, authors speculate on what Chinatown could be like in 2050 and provide new ways of seeing the present and understanding our relationships to the Chinatown neighbourhood and its community in today’s context. Read together (and in the unspoken spaces between each story) the anthology aims to open up the present to new possibilities for the future of Chinatown while finding joy, laughter, and care even in face of adversity.

The story following this preface offer a glimpse into the anthology as well as a virtual reality (VR) companion that brings these fictional Chinatowns to life as inhabitable architectural spaces. But as we reimagine the future of Chinatown together, we also remind readers that Chinatown is as much defined by what is unspoken as what is recorded. As American author, Toni Morrison once stated, “history is made by the definers, not the defined,” and this project seeks to not only find new definers but also challenge what it means to “define” something in the first place. In so doing, this project seeks to embody what marginalized communities have known for some time—namely, that all that is written is not necessarily all that is, and what is remembered extends far beyond what is recorded. In so doing, the reimagined future of Chinatown is found in the anthology not as words or representations, but rather through the silences between the stories, through the relational affects the virtual reality architecture invokes, through the shared lived experiences across divergent stories, and through the labour of memory necessary to experience the depths and meanings of Chinatown that a single monolithic story is not able to tell. To pre-order the Chinatown 205 anthology and for more information please visit www.reimaginingchinatown.com

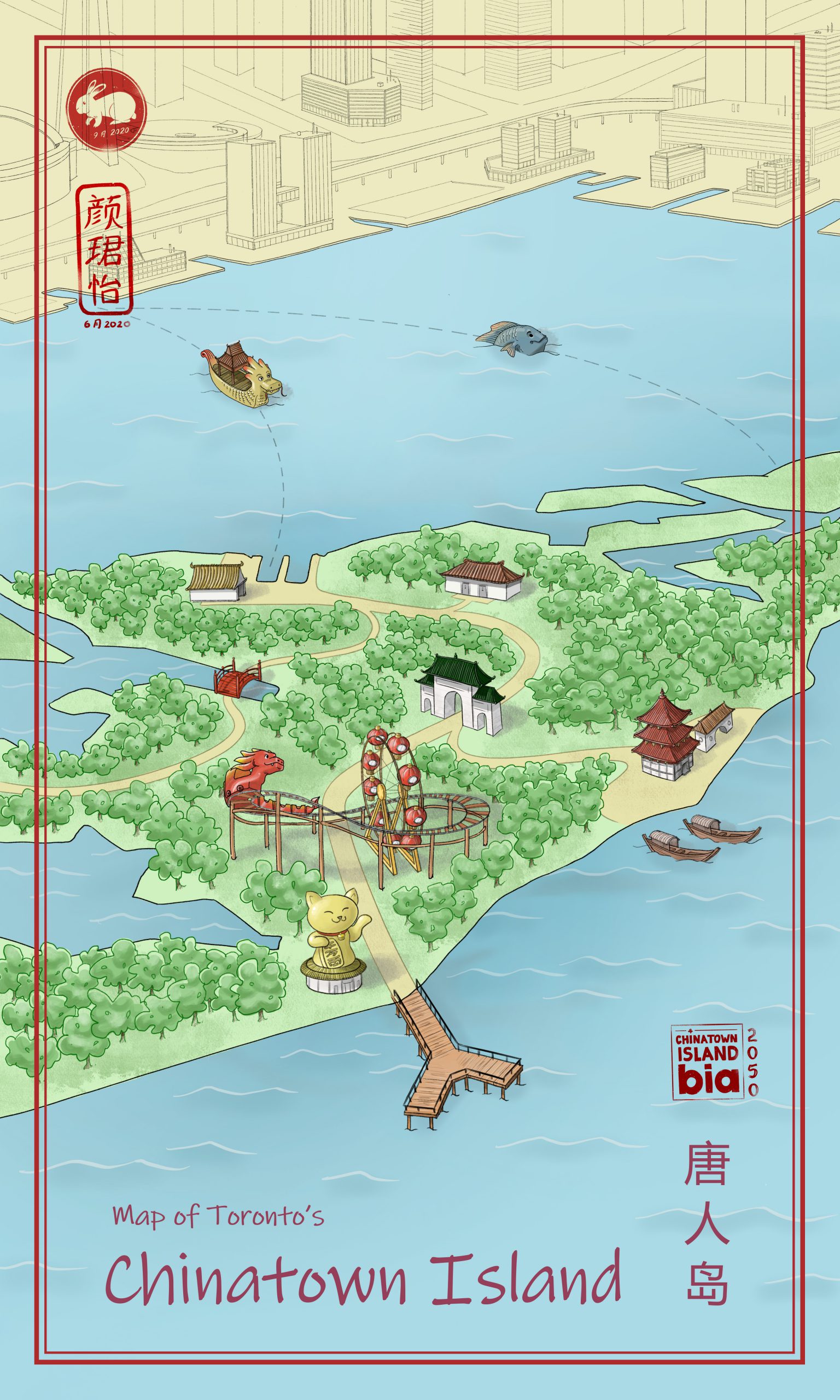

“Chinatown Island” by Amy Yan

Ma Ma says that we used to live in Chinatown. That our house near the corner of Boulton Avenue and Gerrard Street East used to be at the heart of what was the city’s Chinatown East.

“I know that this area used to be Chinatown East, before the pandemic changed everything in 2019,” I say as we cross to the south side of Gerrard and Broadview on our way home from the park. “But really, Ma Ma? This used to be a Chinatown?” I had seen pictures of Chinatowns of the past in my history books from school, but our neighbourhood now looked nothing like those pictures.

“Yes,” replied Ma Ma in Mandarin. She always uses Mandarin even though I only want her to talk to me in English. “The Zhōng Huā Mén Gate used to stand just on the corner of that block right there,” she says, pointing to where an e-bike repair shop now stood. She points south down Broadview. “The Urban Outfitters down there used to be a Chinese herbal medicine store. Wai Po always went there to get her red dates. And that vintage record store on Gerrard used to be an open grocery market. They always sold the best white radishes.”

“What was that store then?” I giggle, pointing to the newly opened VaporLyfe! on the other side of Gerrard Street, knowing that it would set her off. MaMa had been strongly against the opening of the new ‘poison store’ (as she put it in Chinese) in our neighbourhood last year, with its flashy hologram window display and bright neon green lights. Without fail, she would bemoan its presence every time we passed it on our way to the park. “We should have moved a long time ago,” she would mutter under her breath. “We don’t belong here anymore.”

“That used to be Leung’s BBQ Shop,” she said, a hardness coming into her voice. “Mr. Leung actually was one of your Wai Gong’s friends.”

“What was–”

“Mi Mi, another time, I will answer your questions. But right now, we should hurry home.”

Illustration of Chinatown Island by Amy Yan. Image Credit: Linda Zhang and Amy Yan

* * *

“Ma Ma!” I yelled when I got home from school the following day. “I have a field trip form for you to sign!”

Ma Ma emerged from her small home office with a sigh. She looked tired and had her long hair swept up in a tight bun on the top of her head. Whenever she did this, I could not help but notice all the white hairs she had hidden in the layers below. She pushed her large glasses up her nose and looked disappointingly at me. “How many times have I asked you to keep your voice down when I am working?” she asked. “I could have been in a meeting.”

“Sorry,” I said, as I swiped the screen of my school tablet in her direction, sending her the form. “I wanted to make sure I didn’t forget. We’re going on a field trip tomorrow and I need you to sign it so I can go.”

“To Chinatown Island?” Ma Ma said, pulling the form up on her watch and reading the hologram display that popped up.

“Yea, you’ve never taken me before and Ms. Britton is going to make us write a paragraph on why Chinatown Island is important.”

“I don’t think you’re ready to go tomorrow,” Ma Ma said.

“But why?!”

“Because you don’t know what Chinatown Island is yet.”

“Yes, I do! We learned all about it in history class today.” I took a deep breath, ready to impress Ma Ma with everything I had learned that day. “The 2019 Pandemic caused all of the small shops in the old Chinatowns to go out of business, because people weren’t allowed to go out and buy anything in person. This caused all the old Chinatowns to close down and the Chinatown BIA didn’t know what to do because there was nobody that could stay open after the pandemic ended. So they got together and decided to create a whole new, awesome-er Chinatown on the old Toronto Islands and they put cooler things in it, like a giant lucky cat hotel (that has a moving arm!) and a whole bunch of cool carnival rides so that people could go there whenever they wanted and enjoy the China theme park and drink bubble-tea and eat Chinese food and also see a super big Chinatown Gate replica. So there! I know about all of it. Please can I go tomorrow, Ma Ma?!”

“No,” said Ma Ma.

“Aaargh! Just let me go!”

“No,” repeated Ma Ma. “That is not what Chinatown Island is.”

“But it is! That’s what we learned in class,” I protested.

“Chinatown Island is not a bigger, better Chinatown, Mi Mi. When I was a little girl, Chinatown was a place where I could go and feel like myself. Why do you think Wai Po and Wai Gong decided to live here, where Chinatown East was, when they first came to Canada?”

“But can’t you still feel like yourself while you are having fun?”

“Sure,” said Ma Ma, “but the fun is making you forget why Chinatown Island was built in the first place. It wasn’t built for us, it was built to seem like it was for us. After the pandemic, the city’s Chinatowns couldn’t sustain themselves anymore, but Toronto needed a place that still seemed like Chinatown and still was a place that people wanted to go to. When the BIA backed the project in an attempt to relocate some of their businesses, it made Chinatown Island look even better.”

“But if some original shops moved there, doesn’t it make it the same, just in a different place?”

“Leung’s BBQ was actually one of the shops to move,” responded Ma Ma quietly. “Your WaiGong told me that it was really hard on Mr. Leung, but in the end, he had to go or the business would go under, and he had to support his family. But the shop was never the same after the move, no more roast duck and pig hanging in the windows. They even stopped making it for a while.”

“Why?”

“Because they wanted to avoid anything that would scare away customers who were not Chinese, and everybody was worried about cleanliness at the time,” said Ma Ma. “But Chinatown is not a theme park, no matter how successful Chinatown Island has ended up becoming. Chinatown is a place where we can feel like we belong. And I can’t feel like I belong there.”

I sat for a second, not knowing how to respond.

“Do you understand now, Mi Mi?” Ma Ma asked.

I nodded slowly, knowing that any sign of me not understanding would send Ma Ma into another long explanation.

“If you understand, then I suppose I can let you go tomorrow,” continued Ma Ma, signing the form with her finger and swiping it back to me. “But just remember Mi Mi, Chinatown Island is not what you think it is.”

Virtual reality companion of Interval by Eveline Lam. Image Credit: Linda Zhang, Maxim Gertler-Jaffe, Margarita Yushina, Reese Young and Meimei Yang

* * *

I practically skipped off the ferry as it docked itself on Chinatown Island the following afternoon.

“Where do you think you are going Minnie?” yelled Ms. Britton breathlessly as she struggled to get herself down the ramp, one hand on the handrail and the other gripping her purse and marking bag. She was a large old woman who always seemed to wear the same flower pattern skirt and open-toed sandals year-round. She lumbered off the ferry with the rest of my class trailing behind her. “I want us all to stay as a group until I have done a final headcount and set up our field trip trackers. There are just too many people here and I don’t want anyone to get lost.”

Ms. Britton then proceeded to shepherd all of us to a small grassy area off of the main path to do a roll call of the students who had come on the trip. Once she had done that, she flipped open her marking bag and produced a large electronic tablet and a handful of blinking bracelets. “Now,” she said with a huff, “time to set up your field trip trackers to make sure I can keep an eye on you all as you do your exploring. I’ve never had to set this up before, so you all shall have to bear with me.” She then began fiddling with the buttons on the display. “These darn things,” I heard her mutter under her breath, as all of the bracelets suddenly stopped blinking and the display began playing an alarm sound. “We never had to use these back in my day.”

I sighed, knowing that Ms. Britton always struggled with the technology we had at school and it could be a long time before she figured out how to use the trackers. So I took the time to look around. We were still on the edge of the island, in the tree-dotted belt of grass that ran all the way around its perimeter. l knew that the main attractions were further down the path that started from the ferry docks and bisected the island vertically.

Even though it was already the afternoon, there were still many tourists coming off the ferry. They were all heading along the path to the centre of the island, with cameras and maps of the island pulled up on their hologram watches. I vibrated with excitement when I realized I could see the top of the Lucky Cat hotel peeping above the trees from where we stood. I could almost smell the xiao chi that I knew vendors sold further down along the path–

“Minnie are you listening to me?” Ms. Britton’s annoyed voice reached my ears. I turned to see her standing in front of me with a tracking bracelet in one hand and the other hand on her hip. “This is important Minnie, I need you to listen to me

and I won’t repeat myself again. This bracelet is the only way I can monitor you while you are exploring the island. We’re only here for a couple of hours and when it is time for you all to return to the dock to go home, the bracelet will buzz. You must come back to this spot, do you understand?”

“Yes, Ms. Britton,” I said, as she slipped the bracelet over my hand and tightened it on my wrist.

“Ok students!” said Ms. Britton, turning back to the rest of the class. “You all may go explore now. Remember to think about why Chinatown Island is important for your essay tomorrow!” But by this time we had already deserted her, running down the path to the heart of the island.

Virtual reality companion of Interval by Eveline Lam. Image Credit: Linda Zhang, Maxim Gertler-Jaffe, Margarita Yushina, Reese Young and Meimei Yang

* * *

At first, Chinatown Island was everything I thought it would be. Ma Ma’s words of caution did not even cross my mind as I rounded a bend in the path and the heart of Chinatown Island lay before me.

On either side of the path, extending a full city street block in length, were small storefronts, in front of which vendors had their goods spread out for all to see. There was a store for jiǎn zhǐ, outside of which an elderly ā yi was demonstrating an intricate paper cutting pattern to a rapt crowd of tourists. There was a store for Chinese ceramics: blue and white vases, sets of colourful rice bowls and soup spoons, all on display and glinting behind the glass storefront window. There was a souvenir shop selling every conceivable red item, from collapsible paper lanterns to fridge magnets to calendars. There were too many to take in all at once. And of course, there were the stores for the food! Despite the large groups of tourists that were on this stretch of the path, as I walked along, different aromas wafted through the crowd and towards me on the path: the milky aroma of bubble tea, the eggy goodness of freshly baked egg tarts and buns, the comforting aroma of fried rice.

But my eyes were fixed upon the carnival area further down. At its entrance stood the Chinatown Island Gate. It was an exact replica of the Zhōng Huā Mén that had once stood at the intersection of Gerrard and Broadview in our neighbourhood. Its green pagoda roof stood out above the leaves of the trees around it and two stately guardian lion statues stood in front of the three arches of the gate. A dragon-shaped roller coaster cart, complete with flowing whiskers and moulded scales, suddenly soared into view behind the gate, riding on flaming red rails through the air. Just next to it, a large carnival wheel with golden spokes and lantern-shaped seats rotated rhythmically around a flashing five-pointed star. I watched as the wheel slowed down, the ride coming to an end. All the passengers were let off, seat by seat.

It all was so colourful and bright, that for the first few minutes I just stood there and watched. Another group of people got on the Ferris wheel and the lanterns started to make their way around again. The dragon coaster looped around itself and the passengers screamed loudly, lifting their arms up in the air. The Lucky Cat Hotel, visible in the distance, had its large face pointed east and its giant arm waving slowly like an inverted pendulum. A pattern soon started to form: the Ferris wheel would come to a stop as the dragon coaster would launch itself into the air, excited tourists would get on and off the rides and wander back down the path, while all the time the Lucky Cat would wave its paw back and forth unceasingly.

Maybe it was because I was slowly getting used to seeing it all in person, but as this pattern formed, my excitement started to disappear. Oddly, I started to feel that the whole scene was somehow unfamiliar. All the elements—the lanterns, the dragons, the Lucky Cat—were things that I had seen or heard about from Ma Ma growing up. They were not unfamiliar to me. But seeing them all come together in the form of a carnival made them feel foreign and somehow unrecognizable.

I tried to shrug it off, remembering how much I had wanted to come here. It probably was just that I had been staring at the same thing for too long.

Virtual reality companion of Chinatown Island by Amy Yan. Image Credit: Linda Zhang, Maxim Gertler-Jaffe, Reese Young and Meimei Yang

* * *

Leaving the carnival area, I decided to head back and get something to eat. I remembered smelling freshly baked egg tarts on my way over to the Ferris wheel and my mouth watered. As I went about searching for the bakery I passed earlier, I saw two of my classmates standing in front of a storefront window, interested by something going on inside. I walked towards them and saw that they were looking into the window of a BBQ shop. Just inside the window hung eight perfectly roasted ducks, their crispy, golden brown skin shiny with grease. Below them hung several strips of chā shaō, from which excess fat was still dripping into a steel pan below. But both of these paled in comparison to the whole roast pig that was dangling on a large hook by its hind legs, the crackly, crisp skin on its back facing out towards the street.

I had only ever seen windows like this in history books from school and in pictures that Ma Ma had shown me from her childhood growing up in Chinatown East. There were so few people that knew how to make Chinese BBQ now in the city— the tradition pretty much stopped being passed along after the pandemic—that MaMa only went through the trouble of getting roast duck or pork when there was a special occasion in the family. This was because she had to drive all the way out to Scarborough (where one small shop still operated) in order to get it. But the store never had their products hung up in the windows.

As I was admiring the hanging meats, I could hear my classmates chatting between themselves.

“It’s so weird…” I heard one of them say.

“You can still see the eyes and ears!” shuddered the other.

I turned to them, my face flushing. I wanted to tell them that it wasn’t weird and that it tasted really good. I had always looked forward to the occasions on which Ma Ma would make the trip to Scarborough, knowing that she would return with takeout boxes full of the delicious meats. But before I could say anything they turned to me.

“Do you eat that?” one of them asked pointedly.

What she had said not particularly unkind, but they were standing together and I was on my own. I could feel a hot embarrassment rising up from my cheeks to my ears, although I tried my best to fight it. I wondered if they could see my face turning as red as it felt.

“Y-yea, I have,” I stammered a bit, trying to hide my feelings. “I’ve tried it before.”

“Ewww,” said the other. She jammed her finger into the window, pointing at the pig. “Have you tried to eat the head?”

“I mean, we don’t usually–” I began. Ma Ma’s words from yesterday suddenly came back into my mind. “I can’t feel like I belong there,” she had said. I glanced towards them again and suddenly felt as though I was on display. That all the things that I had grown up with were putting on an overproduced show for tourists to gawk at, and that somehow, I was a part of the attraction. Was this the same feeling I had had over by the carnival rides?

“Can I help you?” A deep voice sounded suddenly from behind me. I whipped around to see a tall Chinese man standing in the doorway of the shop. He looked to be about my Ma Ma’s age and evidently worked in the shop as he wore a chef’s outfit and hat, and had a grease-stained white apron around his waist. He looked towards my two classmates.

They froze.

“Um, no sir!” they said in unison. They quickly backed away from the window and disappeared among the other tourists.

The man turned to me.

“Oh,” I said, “I was just admiring your window display. I’ve only seen a BBQ window display like yours in books.”

“Yep,” he replied proudly, “I decided to start setting up the window display only a little while ago. My father never did it after the pandemic, but I thought that it was time. Before then, I had only seen them in books too.”

I nodded. It certainly was an impressive display. I then noticed the monogram on his shirt: Leung’s BBQ. “Wait,” I asked, “is this Leung’s BBQ from the old Chinatown East?”

“Yes, it is!” the man replied, surprised. “How do you know about that?”

“My mom told me that you used to be located right by Broadview and Gerrard,” I said, “and she said that my Wai Gong used to be friends with Mr. Leung.”

“Really! How fortunate you’ve dropped by. No one your age has ever brought up Chinatown East to me before.” He was clearly impressed. “I am Charlie Leung, Mr. Leung was my dad. He was the one who moved us here after the 2019 Pandemic shut down Chinatown East. Why don’t you come in and take a look?”

He opened the door wider and the rich aromas of Chinese BBQ welcomed me inside.

* * *

I can’t quite remember how long I spent in the store. Once I was inside, Mr. Leung offered me some duck and pork from the window and, while I ate (and complimented him on how good it all tasted), he started explaining some parts of the store to me. He then started to prep slabs of raw pork with his family’s secret mix of ingredients for the following day, all the while talking to me about some of his experiences growing up and working on the island. He was so friendly and open that after I finished eating (and tried to pay him for the food unsuccessfully), I found myself asking if I could help with the cooking. “Oh, really you don’t have to,” he said. Then seeing my insistence, he continued, “but if you really want you can help me wash and prep the vegetables. We have our monthly vendor gathering today and I could use some help with the side dishes.”

“What’s the monthly gathering?” I asked, as I took off my tracking bracelet and placed it next to me on the counter so it wouldn’t get wet as I washed the vegetables.

“My dad liked to host a small get together for all the other vendors each month,” he replied. “It was his way of saying thanks to the community and so I continue it now that I’ve taken over. Leung’s BBQ would have gone under a long time ago if it wasn’t for the support of the other vendors on the island. I guess porcelain bowls and jian zi are just more palatable to the tourists than what I’ve got to offer.”

I nodded silently. I got started on washing the lotus roots, the white radishes, green onions, and myriad other vegetables he had laid out like I had so often helped my Ma Ma do at home, and when she was still alive, my Wai Po. It was something that I had always loved to do. Back then, I would have to stand on a stool so that I could reach the sink to scrub at the vegetables before handing them one by one to Wai Po for her to chop up. It was a ritual that I always thought of as private, something belonging to us that my family had just kept on doing after the pandemic wiped out so much of our space from the city.

Even though I was born long after the pandemic, throughout the years, Mama had managed to convey to me how much loss she saw and felt, and so to some extent I had felt it too, although I’d never let myself get too bothered by it. In school and with my classmates, it was easy to ignore the fact that I was Chinese. Diversity and inclusion were ideas that were constantly preached in class, but I would also just never bring up anything that I knew they didn’t know. It was just easier that way; they wouldn’t feel awkward and I wouldn’t feel different. Which was why I was so confused that I was finding myself feeling so at home in the very same place where, earlier, I had some of my first feelings of being pointed out as different in a way I had no control over.

It wasn’t until Mr. Leung had started cooking the vegetables on the stove and asked me if my parents knew where I was that I remembered the time and my tracking bracelet. I ran over to where it lay on the counter. It must have been buzzing and buzzing for a long time because it now was completely out of battery. “I was here with my class. I should have gone back when my bracelet buzzed but I forgot!” I said hurriedly. I looked out the window and panicked when I saw that the crowds of tourists had thinned significantly and that long shadows were already starting to stretch along the path. “They must have gone! What time is it now?”

“It’s 6:34.” Mr. Leung replied, quickly turning off the stove and walking with me to the door. “The Island is closing pretty soon, at 7pm. I really am sorry that I kept you so long, I should have asked you way earlier but I got caught up in my stories.”

I dashed outside with Mr. Leung following. I was hoping to see the outline of Ms. Britton in her flower print skirt somewhere along the path, but also knew all too well that she had probably left with the rest of the class hours ago. As I stepped outside, I heard a voice calling my name and suddenly, out of nowhere, hands grabbed me by the shoulders and spun me around. I looked up and was surprised to see Ma Ma, her face lined with worry and her eyes scanning me up and down to make sure I was alright. She hugged me close to her and then quickly pulled away. “Mi Mi,” she began angrily in Mandarin, “what were you thinking? You had me so worried! Why didn’t you listen to Ms. Britton and go back when you were supposed to?”

“But Ma Ma–” I began.

“No,” interrupted Ma Ma, “I knew I should not have let you come here in the first place. Where were you this whole time? Your school had to be alerted and we’ve been looking all over for you!”

“She was with me,” said Mr. Leung, cutting in from behind me. “I’m so sorry, but I was showing your daughter my store and lost track of time. It’s my fault that she missed going back to her class.”

Ma Ma looked towards him, a mingling of anger and confusion on her face. But her eyes landed on the monogram on his shirt and her expression shifted suddenly. “Charlie Leung?” she said, surprised.

“That’s me,” Mr. Leung said a bit sheepishly, a look of surprise also flashing across his face. “I recognize you now. You must be Annie. Your dad used to bring you all the time to my Ba’s store in Chinatown East.”

“That’s right. I can’t believe you’re still here. I mean, I knew that your dad moved the business here after the pandemic. But–” Ma Ma’s eyes drifted behind Mr. Leung to the display of Chinese BBQ that I had marvelled over earlier. “How is this here?” she gasped in surprise. “After the businesses moved my Ba said that it was all gone, and the whole store had changed. I’ve never seen a window display like this since I was a little girl.”

“Yes, it was very different after we moved here,” Mr. Leung replied quietly. “My Ba had the hardest time with all the new rules that were set out for Chinatown Island. He had to change everything about the way he ran his business in order to stay operational. And, he couldn’t bear the sight of those rides as they were being built.” He gestured towards the Chinatown gate and the carnival area. “They have never belonged to us. They were always for the tourists.”

“They’re superficial,” agreed Ma Ma. “I’ve never wanted to visit Chinatown Island because of that. I wouldn’t have let Mi Mi come if it wasn’t for her field trip.”

“But, you know, my Ba was never superficial,” said Mr. Leung softly. “Yes, he had to do things to stay in business, but he never forgot who he was and neither did any of the other vendors. They all remembered what Chinatown is supposed to be, and as long as that stays the same we can still find a sense of belonging with each other. That’s something that the pandemic couldn’t take away.”

I looked around me on the path of Chinatown Island. The lights in the carnival area had been turned off and, with the rides now shrouded in shadow, the shops stood out against the fading light. The vendors and their families were all busily taking down their displays for the evening. Warm lights shone from inside the shops as they chatted in Chinese to their neighbours about their day and helped each other pack up. An elderly couple walked down the center of the path and waved at Mr. Leung. “We’re coming over for the meeting soon!” they called and Mr. Leung smiled and waved back. I recognized the elderly woman as the ā yi who I had seen earlier in the day at the jian zi store.

I looked at Ma Ma and saw her gazing around her as well. There was a look in her eyes that I hadn’t seen before. A sense of belonging that was never there when she looked at any other place in the city.

“Well,” she said after a long pause, “I think it’s time to go, Mi Mi. It’s late.”

“Will we come back, Ma Ma?”

“Yes, Mi Mi. Very soon.”

Amy Yan is a fourth-year student at the Ryerson School of Interior Design. She is interested in exploring the intersections between design and storytelling with her work, and in finding new ways to be able to convey a narrative, both visually and spatially. Her passions include illustration, 3D prototyping and longboarding. IG: @aypproductions

Linda Zhang is a registered architect, licensed advanced drone pilot, and artist. She is a principal and co-founder at Studio Pararaum and assistant professor at Ryerson SID. Her project Reimagining Chinatown 2050 explores memory, cultural heritage, and identity as they are indexically embodied through emergent technologies (including 3D scanning and virtual reality) as a means of community engagement and collection envisioning.