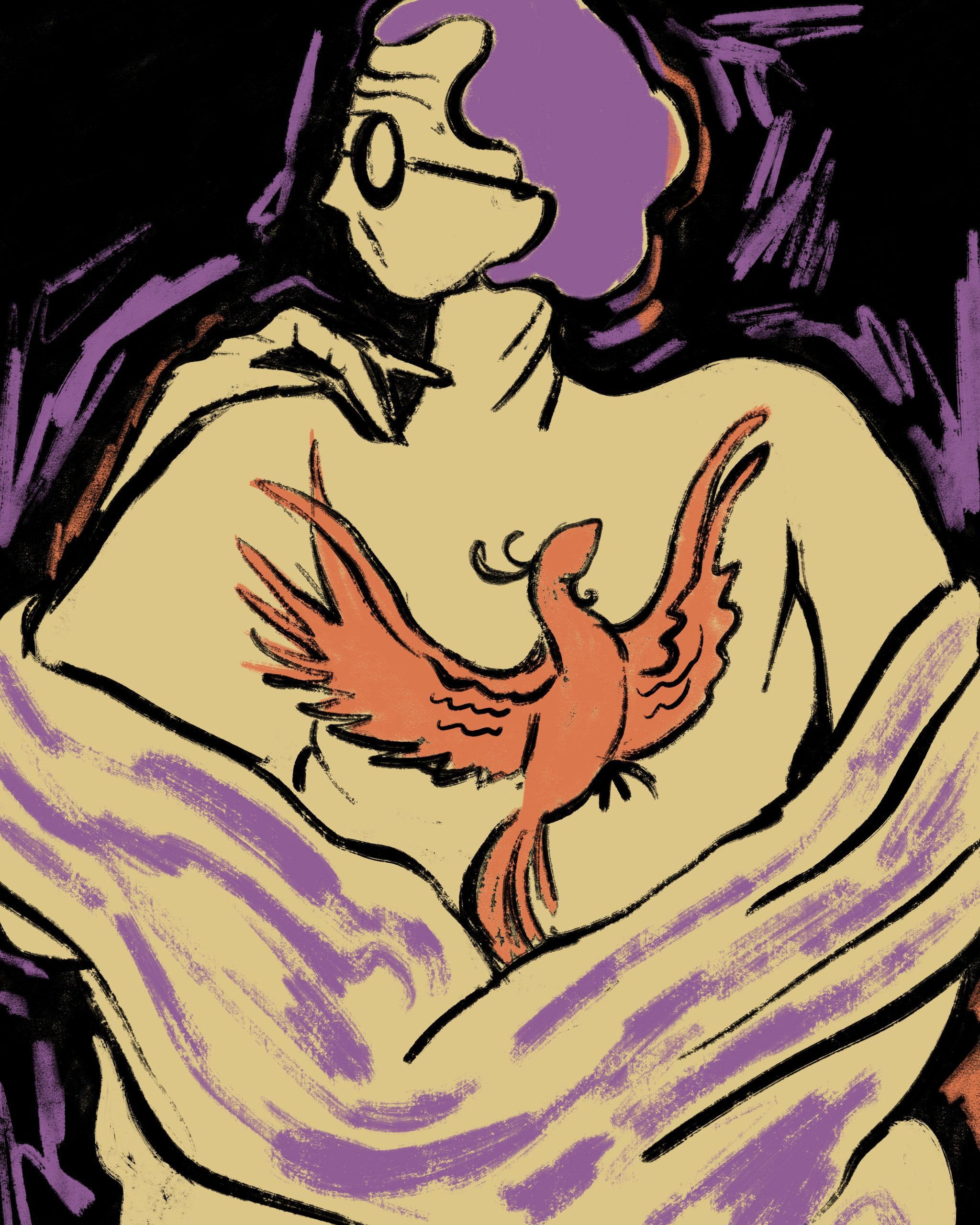

Illustration by Arty Guava

My left earlobe throbs with a familiar pain. A few weeks ago, I removed the infected earring to give the wound some air. After a careful sterilization, I ask my sister to stab it back.

Why can’t you just do it? she complains, even though we both know the answer. Every time the needle brushes my ear, I’m paralyzed by my grandmother’s ghost, whose phantom presence bears the same coarse hands as she did in life.

*

Here’s what I remember:

A translucent, paper-thin earlobe. My grandma, Nai Nai, its bearer, cradling me on her lap, perched on the floral stool at her vanity.

That summer break was claustrophobically wet, so my sister and I resorted to rifling through our cluttered attic as we listened to fat raindrops spite our playground dreams. We found a treasure trove of old jewelry in the attic and rushed it to Nai Nai’s room to stake our claims. The lacquered box consisted primarily of clunky clip-ons and brooches, but a few stood out luminously like stardust among rust.

These accessories carried no explicit significance, although their heavy weight implied an intrinsic value to my naive, ten-year-old self. Given our scattered family tree, I knew these weren’t heirlooms; rather, they were leftover adornments, collectibles too precious to throw out but too vague to have any attached sentiments.

Bouncing me up and down her thigh, Nai Nai turned to the mirror and pinched an emerald earring with its point toward her lobe. With one swift motion, she plunged the needle through that translucent, paper-thin earlobe.

A drop of blood materialized—ruby red staining the gold. She dabbed the wound delicately until the tissue drenched a scarlet hue.

*

These are the contours of my knowledge as it pertains to my grandma:

She fled to Taiwan from communist China after months of eating rice that was undercooked and hard from the lack of water and other natural resources. The weevils that hatched within the sacks provided the protein that promoted her and her family’s survival.

They wound up in Kaohsiung, where my great-grandfather worked at a stylish factory that paid well; a job that safeguarded a favorable social status about town. She lived with her father, mother, and three siblings until she was sixteen years old, at which point she married my Ye Ye, who was twenty-eight.

They endured a happy marriage, for the most part.

My father was born when she was sixteen and a half. The agony she underwent to produce this heir was so intense it was only overshadowed by the joy at his gender: his boyhood ensured she would never have to suffer through childbirth again.

Her life-creating, near-death experience was one of the only stories in our family lore.

As my father withdrew from her womb, all she saw was white. She was plucked by a visionary phoenix upon approaching the alabaster abyss. The bird erupted, with my Nai Nai still clutched in its talons, and dissipated in the fluorescence like volcanic ash. Only when she heard my father’s cries did she open her eyes and rise from the flames.

Pain begot beauty. She never forgot that lesson.

*

After she affixed the backing to the emerald, I whispered, Does it hurt?, as if her eardrums had also been afflicted. Not as much as you think, she comforted in Mandarin. Her forlorn eyes betrayed the secrets hidden behind her smile.

On her lap that day, as she patted my cheek with her calloused palm, I tried my best to decipher the message she was trying to signal. Although the volumes were too heavy to translate, one thing was clear: we spoke the same language of pain.

Re-piercing her own ear became her gateway to more intense forms of body modification.

When I started high school, I pierced her tongue and dragged it down the ridge until it split.

During my first break home from college, I ran my fingers over the swirls I cut in her wrinkles, which healed beautifully into embossed scars. After my college graduation ceremony, I branded my Ye Ye’s name in traditional Chinese on her right thigh.

We snipped, cut, pierced, dyed, burned until she didn’t look like my grandma anymore. Or any grandmother, for that matter. My parents, placated by the tradition of respecting their elders, couldn’t object.

Through online videos, I learned how to make a tattoo gun out of a mechanical pencil and guitar string. My bedroom became a dark and inky lair, littered with grapefruits tattooed with smiley faces, bananas enhanced with intricate lettering, lemons adorned with roses. Honeydew was my favorite to practice on, for its large surface area, ability to hold ink, ease with which the needle dragged, and uncanny resemblance to human flesh. I took particular pride in a melon I covered with a nine-tailed fox resting on the branch of a Chinese pistache tree and admired it on my desk until its gradual and inevitable decay.

*

In Chinese, bitterness is eaten like unripe fruit. To eat bitterness means you persevered through a hard life, rife with struggle and survival. My parents did everything in their power so my sister and I would never know its taste. To them, it deformed and decayed.

My Nai Nai’s skin wore down with the marks of time and suffering. Of bitterness.

Thinking back, it’s hard to tell whether she wanted to hide or highlight—to decorate or mutilate.

The line is blurry: so much of beauty entails suffering. We do it every day through shaving, plucking, lasering, squeezing, bleaching, waxing. Skinny waists in corsets in Victorian England, lotus feet achieved through foot binding during the Qing dynasty, youth-giving paleness by way of leeches in the Middle Ages.

Whatever her reason, I acquiesced. Although I was born in a Western world, I am still the daughter of my ancestors: I respect my elders. I never said no.

*

We always did her transformations in her bedroom, which had the best natural light in the house. Even though she moved in years ago, the room was sparse with few personal effects. Her prized possession was a collection of classical CDs held in a circular container that resembled a jello mold.

Nai Nai spent hours sitting upright on her bed, with hands folded across her lap, eyes closed, and head bobbing lightly—lifting for crescendos, bowing at codas.

But whenever we worked together, she would keep her eyes closed to silence, never flinching or reacting to the blade, needle, brand, fire. I always wondered what she was thinking. Even if she had told me, I’m not sure I would have understood.

*

On her eighty-eigth birthday (an auspicious year in Taiwanese culture), I gave my grandma her first tattoo (her second, if you count her microbladed permanent eyebrows). It was a magnificent piece, covering her back with a powerful phoenix borne of a bloody fire. Afterwards, we went out to eat at the fanciest restaurant in our small town: Red Lobster. Nai Nai liked their cheddar biscuits.

In keeping with birthday tradition, we ordered long, unbroken noodles — linguine that could be twirled, spaghetti that could be slurped — and fed them to Nai Nai so her longevity could be preserved.

We caused quite a scene: me, my mom, my dad, my sister, and my grandma, with her electric purple hair. When Nai Nai ordered, an audible gasp escaped the teenage waitress when she saw her serpentine tongue.

As we feasted, we ridiculed the large, American portions and relished in the reactions of the other patrons. Their whispers were our ammunition so we loaded up our weapons in the face of their shock and fired back with our defiant joy.

*

Three, two, one…

My sister counts down as a warning before shoving the blunt needle through my earlobe. I brace for the pain, which will be acute, then gone—leaving a beautiful emerald in its place.

Jun Chou is an Asian-Canadian writer from Richmond, B.C. and currently based in Brooklyn. During the day, she works on the NYT Cooking App. At night, she’s writing her debut novel. You can find her online @junnotjune.

Lay Hoon aka Arty Guava is an Illustrator and Graphic Designer based in Vancouver. She grew up in Malaysia and spent most of her adult life in Singapore before moving to Canada. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Bioengineering but chose to make a career switch after about 1 year of working in the field. Art and Design have always been her calling. She is passionate about culture, people and nature and how these themes interact with each other. Her work is available at artyguava.com/illustration

1 comment

I loved reading this piece. I especially connected to the notion of pain, freedom, and rebellion across generations.