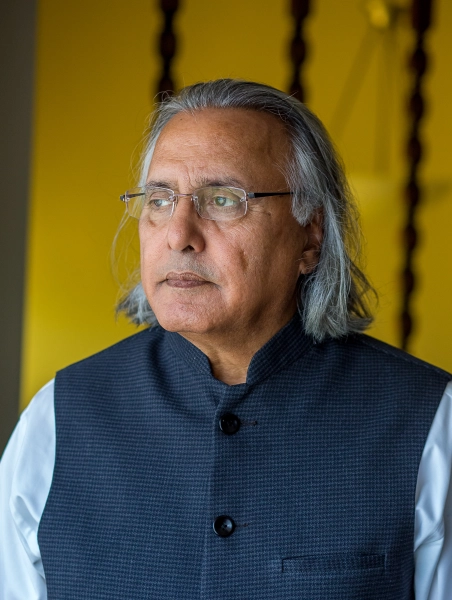

Ujjal Dosanjh was born in a village of India’s rural Punjab in 1946, mere months before the midnight of India’s independence in 1947. Ujjal migrated to Britain in 1964 where he shunted trains in the British Rail goods yard in Derby, made crayons in a Bedford factory, worked in a car parts plant in Letchworth and helped edit a Punjabi weekly in London while immersed in reading and learning to speak English listening to BBC One. A lifelong activist for social and economic justice, Ujjal campaigned for better legal rights for farm and domestic workers, practiced law and jumped into electoral politics becoming a BC MLA, Attorney General and Premier and subsequently a member of parliament and Minister of Health for Canada. Retiring in 2011, he wrote his autobiography Journey After Midnight published in 2016- it made BC’s Bestseller list for several weeks—before turning to fiction to write stories that he had encountered in his life some of which had travelled with him. Living in Vancouver since 1968, all his Canadian life, he enjoys gardening, walking, writing and spending time with his six grandchildren. Ujjal’s debut novel, The Past Is Never Dead, set in Banjhan, Punjab and in Bedford, England in the British Midlands of the mid-20th century, published by Speaking Tiger in India, delves into the life of an untouchable Punjabi lad who immigrates to England and how the stranglehold of the caste system travels and remains with him as he fights for equality in Britain.

Ujjal Dosanjh was born in a village of India’s rural Punjab in 1946, mere months before the midnight of India’s independence in 1947. Ujjal migrated to Britain in 1964 where he shunted trains in the British Rail goods yard in Derby, made crayons in a Bedford factory, worked in a car parts plant in Letchworth and helped edit a Punjabi weekly in London while immersed in reading and learning to speak English listening to BBC One. A lifelong activist for social and economic justice, Ujjal campaigned for better legal rights for farm and domestic workers, practiced law and jumped into electoral politics becoming a BC MLA, Attorney General and Premier and subsequently a member of parliament and Minister of Health for Canada. Retiring in 2011, he wrote his autobiography Journey After Midnight published in 2016- it made BC’s Bestseller list for several weeks—before turning to fiction to write stories that he had encountered in his life some of which had travelled with him. Living in Vancouver since 1968, all his Canadian life, he enjoys gardening, walking, writing and spending time with his six grandchildren. Ujjal’s debut novel, The Past Is Never Dead, set in Banjhan, Punjab and in Bedford, England in the British Midlands of the mid-20th century, published by Speaking Tiger in India, delves into the life of an untouchable Punjabi lad who immigrates to England and how the stranglehold of the caste system travels and remains with him as he fights for equality in Britain.

Journey After Midnight: India, Canada, and the Road Beyond is a deeply personal and political memoir. What inspired you to put your experiences into words? What was the process like?

Many friends, colleagues and often strangers encouraged me to write about my journey from childhood to old age and from India to Canada via Britain. For the longest and several reasons I resisted. I have never been in the habit of talking about me or mine; in fact, I have always found it hard to do so. Eventually came a chance meeting with a gentleman connected with the old Douglas McIntyre on a flight from Ottawa to Vancouver who suggested my life story was an interesting one and offered to connect me with the publisher. The discussions ensued. Potential ghostwriters were interviewed but before the arrangements could be finalized Douglas McIntyre was bought by another publisher.

Reminder, my spouse, got on my case and insisted I pen my biography; obviously, she thought nothing of my inhibitions and had more confidence in my ability than did I. It worked and I penned Journey After Midnight and Scott McIntyre, by then my friend, formerly of Douglas McIntyre helped me find Figure1 who eventually published the Journey.

The thought that others might put a different spin on the historical events I had been a part of helped make up my mind to pen the book and document the facts as they presented themselves to me. As well I wanted to make sure my grandchildren knew their elder’s stories—or stories—from the horse’s mouth, so to speak.

One more thing even though telling it might sound vain. Although it was once reported on the front pages of the newspapers, not many people probably remember that for many reasons I was not inclined to run for the leadership of the NDP in 1999. My friends persuaded me that if I ran and won, it would be a historic win, for minorities in particular. Hence I ran. Similarly many believed it was important to document in first person at least the public and political parts of my life. Hence the Journey.

As to the process, I have never kept a journal. I had to rely on my own memory as well as that of my friends, associates, political actors and activists. The stash of clippings organized by my friends and volunteers over the years helped too. The first couple of pages took an inordinate amount of time to compose; thereafter it took me over a year and a half to write 300000 words which I had to reduce to 200000 before my extremely experienced editor slashed another 50000 and whipped the whole thing into shape.

After the initial hesitation had been humbled, I wrote almost every day and thoroughly enjoyed the process.

The Past is Never Dead explores how casteism continues to dictate Kalu and his family’s position within the social hierarchy. What do you foresee in the future regarding attempts to mitigate caste-based discrimination?

I wrote The Past Is Never Dead to document the life of Indian immigrants in mid-20th century Britain and the role caste played in it. From January 1965 to May 1968 I lived in Britain and some of the events recreated and fictionalized in The Past happened to my friends and left a deep impression on me, so deep that I still carry the memory and long wanted to write their story. It is a tribute to their resilience and determination in the struggle for equality which continues today.

Our governments, provincial and federal, have shown little inclination to include caste as grounds of prohibited discrimination. In the case of BC and Ontario, the government’s feeble response has been to argue that they have sufficient tools within the framework of the existing Human Rights legislation to obviate the need for a specific head of protection within it. Such claims by governments are absolutely fallacious and thoroughly misleading. If a specific ground of prohibition isn’t required for caste, why is it required for any other differences for which people are discriminated against?

The government’s response is hogwash.

If the governments believe the passage of time for immigrants away from India will erase caste, history provides ample proof to the contrary. Furthermore, more immigrants from India coming to Canada regularly will inject and invigorate caste distinctions in Canada that may or may not have been on the decline.

I sincerely hope I am wrong in believing that caste in all its perniciousness will be a Canadian reality for a long time to come.

You have had extensive political experience, as a BC MLA, Attorney General and Premier and subsequently a member of parliament and Minister of Health for Canada. What are the most important lessons you have learned throughout your career?

I have been a lifelong activist for social justice and equality; it was that passion for equality, fairness and social justice that eventually thrust me into electoral politics.

Electoral politics was never a career for me as it mustn’t be for anyone. My career happened to be law which I used to earn a living and to fuel my activism.

Contrary to popular belief that one is in politics only when one runs for elections, all of us are in politics regardless of whether we are actively politicking since politics affects us all.

I feel very deeply that one must never go into electoral politics for power, glory or the status that some assume goes with the elected office; to run for any office one must be passionate about ideas and policies that one wants to pursue. I see a lot of people running for offices for which they are ill-suited because they are in the race for the wrong reasons.

We badly need risk-takers in politics.

Late Prime Ministers Pierre Trudeau and Brian Mulroney are cases in point as politicians who took risks and made Canada a greater country e.g., Trudeau for the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and repatriating our Constitution among other things and Mulroney for the Free Trade Agreement, GST and leading the Commonwealth against Apartheid in South Africa, to name a few of their accomplishments.

Ujjal Dosanjh will be featured at LiterASIAN Festival 2024. Please check out the lineup of the festival at https://literasian.com/

1 comment

Looking forward to reading Mr Dosanj’s autobiography.

Left awful Harris Ontario for BC around 2005. Various motivations. Concern about attacks on Universal, Publicly Funded Healthcare . Further research,making use of world-class VPL about George W Bush personally and his admin as war criminals. Regards.