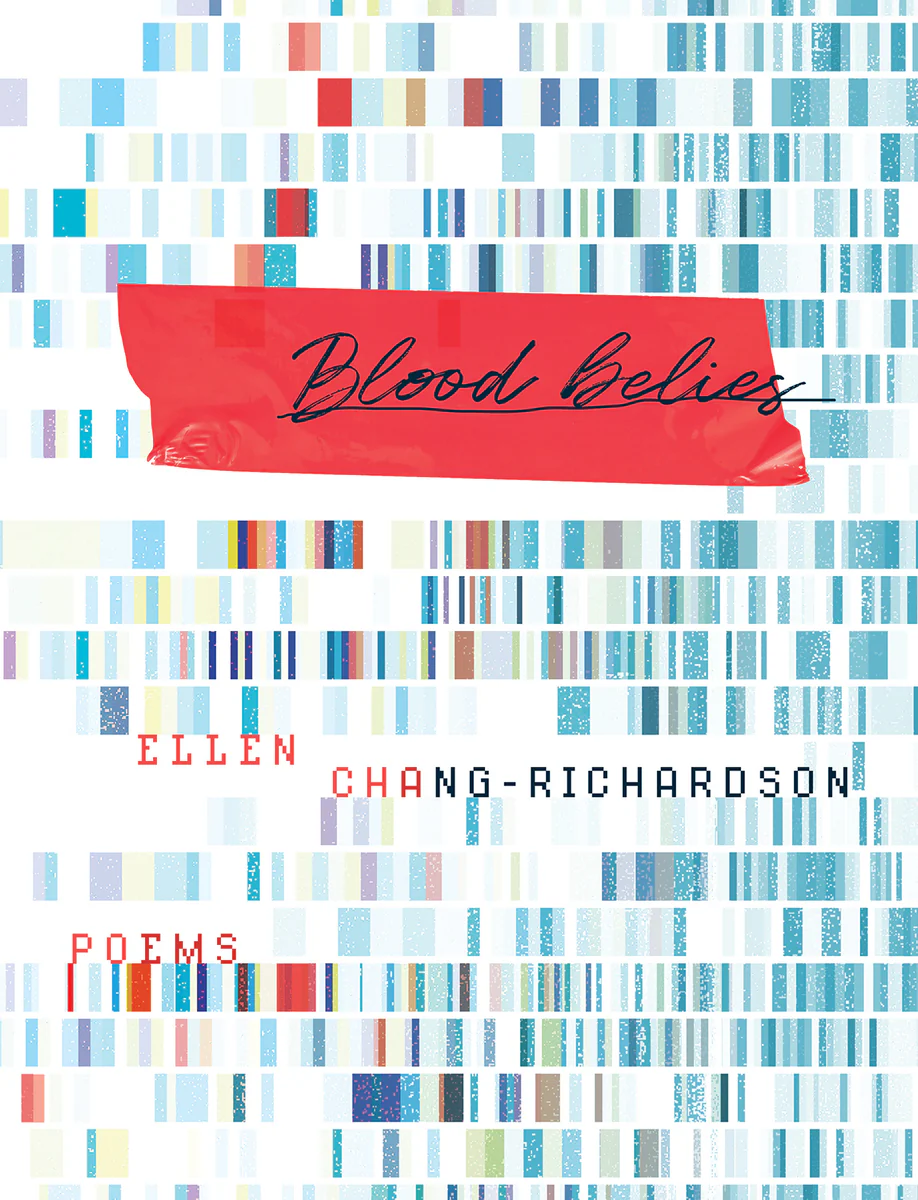

Ellen Chang-Richardson’s debut poetry collection, Blood Belies (Wolsak and Wynn), employs visual art and language to interrogate the nature of history and memory. Through negative space, concrete poetry, and fragmented lines, the book explores the tensions of being Chinese-Canadian—its violence, tenderness, and silence/absence. Chang-Richardson’s speaker is using these silences to “feel the p u l s e of my father’s secrets in my / veins;” they are attempting to recount the history of their father, of themselves, of us—to put language to all of it—through silent pulses. Focusing on the Chinese-Canadian experience, the book mines from news articles, the “Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration” from 1902, and builds off work by other Canadian artists, among other texts, to find language to fill in the absences—if language can even fill in these absences—that the memory leaves: “but memory // has a way // of skewing.”

Ellen Chang-Richardson’s debut poetry collection, Blood Belies (Wolsak and Wynn), employs visual art and language to interrogate the nature of history and memory. Through negative space, concrete poetry, and fragmented lines, the book explores the tensions of being Chinese-Canadian—its violence, tenderness, and silence/absence. Chang-Richardson’s speaker is using these silences to “feel the p u l s e of my father’s secrets in my / veins;” they are attempting to recount the history of their father, of themselves, of us—to put language to all of it—through silent pulses. Focusing on the Chinese-Canadian experience, the book mines from news articles, the “Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration” from 1902, and builds off work by other Canadian artists, among other texts, to find language to fill in the absences—if language can even fill in these absences—that the memory leaves: “but memory // has a way // of skewing.”

The way the book is set up, with entirely blank pages or a wholly blacked out page, the spliced images, and fading text throughout, is all a form of felt silence. This silence isn’t empty; it’s filled with deafening absences: “like // ,… // ,…” where the history of Chinese-Canadians—of the speaker’s father—fills the quietness with dense, tense energy. In a poem called “resonate this,” these silences and absences are pushed to the limit, where a single phrase can take up an entire page. Each flip reveals almost a new poem, from the elliptical “like // … … …” to a concrete poem with fading text, phrases falling like leaves from “two // sugar maples.” The interplay between concrete imagery, fading text, and punctuation-based poems questions whether language can truly capture the story of history and memory.

And to tell these stories, “±,” rather than words, might be necessary. The ± symbol is scattered throughout the book, almost screaming in ambiguity and meaning. According to Wikipedia, it can mean three things: in mathematics, it represents a choice of two values achieved through addition or subtraction respectively; in statistics, it represents a margin of error; in chess, it means there is a clear advantage for the white player. In all these cases, the meaning falls into place pretty quickly. The necessary addition/subtraction is apparent in the fading and resolidifying text of “resonate this”: Honk! / —snow falls on dark heads, defiant (pg. 83) compared to: Honk! / —snow falls on dark heads, defiant (pg. 84). This fading, this addition/subtraction of phrases, questions the voice that Chinese Canadians have, and more so than that, gets to a certain level of absence that a blank page can’t do. The margin of error might be precisely what it is: the margin of error that memory and history reveal. As I mentioned before, one of the significant interrogations of this book is how memory gets “skewed,” if language can reproduce it at all, or if it all comes out as an error:

………....—side

out……. —sider

………….—shift

And, well, the white player having a clear advantage isn’t a formidable metaphor to piece together.

But with all these silences, there is a loud story about the speaker’s father, themselves, and us. Chang-Richardson is asking us to hear the silence of a story left behind by a history of violence and hatred of family and community. Chang-Richardson’s asking us, through silence, to grapple with the weight that Canada has on the community Chang-Richardson’s writing about, about the lack of voice and language to tell the story—the memory and history—of Chinese Canadians.

Alex Deng was born in Guangzhou and raised in Tkaronto (Toronto). Alex has appeared or is forthcoming in the anthology Chickenscratch 2024, Ricepaper Magazine, Canadian Literature, and ROOTed Rhythms. He is working toward his MA in English (Public Texts) at Trent University. He loves eating noodles and reading poetry.