Photo by Sam Herriot

I never went to the funeral of the first body I saw.

Seven kilometres from China’s Great Wall, my grandpa and I stood under the threatening alabaster silhouette of a temple. The tourists that we stood amidst surrounded the foot of the steps, and a scatter of men wearing sage uniforms and frowns yelled orders that disappeared into the crowd. Their harsh voices cut through the meld of warm bodies and distracted me from the abhorrent twist that prickled the back of my neck with its bristles of dark straw. My grandfather’s guilt was as apparent as the rhythmic blooms of breath that escaped people’s lungs every time he glanced at my hair. Unfortunately, knowing the mechanics behind braiding hair wasn’t required during the Cultural Revolution. I jammed my damp white fingers into my pocket, and I didn’t complain about the cold because I saw the elation painted over my grandfather’s wrinkles. We were ushered behind a series of heavy doors that left us in darkness. I held my grandfather’s hand and prayed I didn’t lose him. The once bustling crowd travelled the long hallway in silence. By the time we reached the end, my fingertips had thawed. My anticipation brimmed as we approached a dimly lit red room to the left of the walk, but the feeling sank as the stale smell of something other than wood crawled into my lungs. Between the beautiful display of flowers was a man. A flood of camera flashes distorted his serene face under the glass. I felt spit collect in my mouth as an itch formed in my mind. Somehow, I knew the man was not sleeping. My stiff neck turned to my grandpa as he crouched, pointing to the man.

“That’s Mao Ze Dong, he taught me how to swim as a kid you know? Other kids too, my brothers and sister… see how perfectly preserved he is?”

I dreamt of the man for two weeks after that, his perfect emptiness just beyond my understanding.

See how perfectly preserved he is?

At eight, I sat on the downstairs living room floor, dust glued to my tear-stricken skin, as I contemplated what most adults drank away. My imagination raced marathons around the room like invisible shadows cast by the sunlight of my childish brain. I mourned the absence of my understanding of life. Dreams of Mao from the previous year had since been replaced by the futuristic visions of my grandparents’ funerals. It taunted my mind during class and weighed against my chest while I slept. Like a weed, the instability that was implanted within me began to spread when I realized not even the adults in my life would be able to answer my questions. My mom eventually found me rotting in my cloudy puddle of confusion. She squatted down next to me.

“Mom, do grandpa and grandma know they are going to die soon?”

Her eyes widened, and for a brief moment, she hesitated.

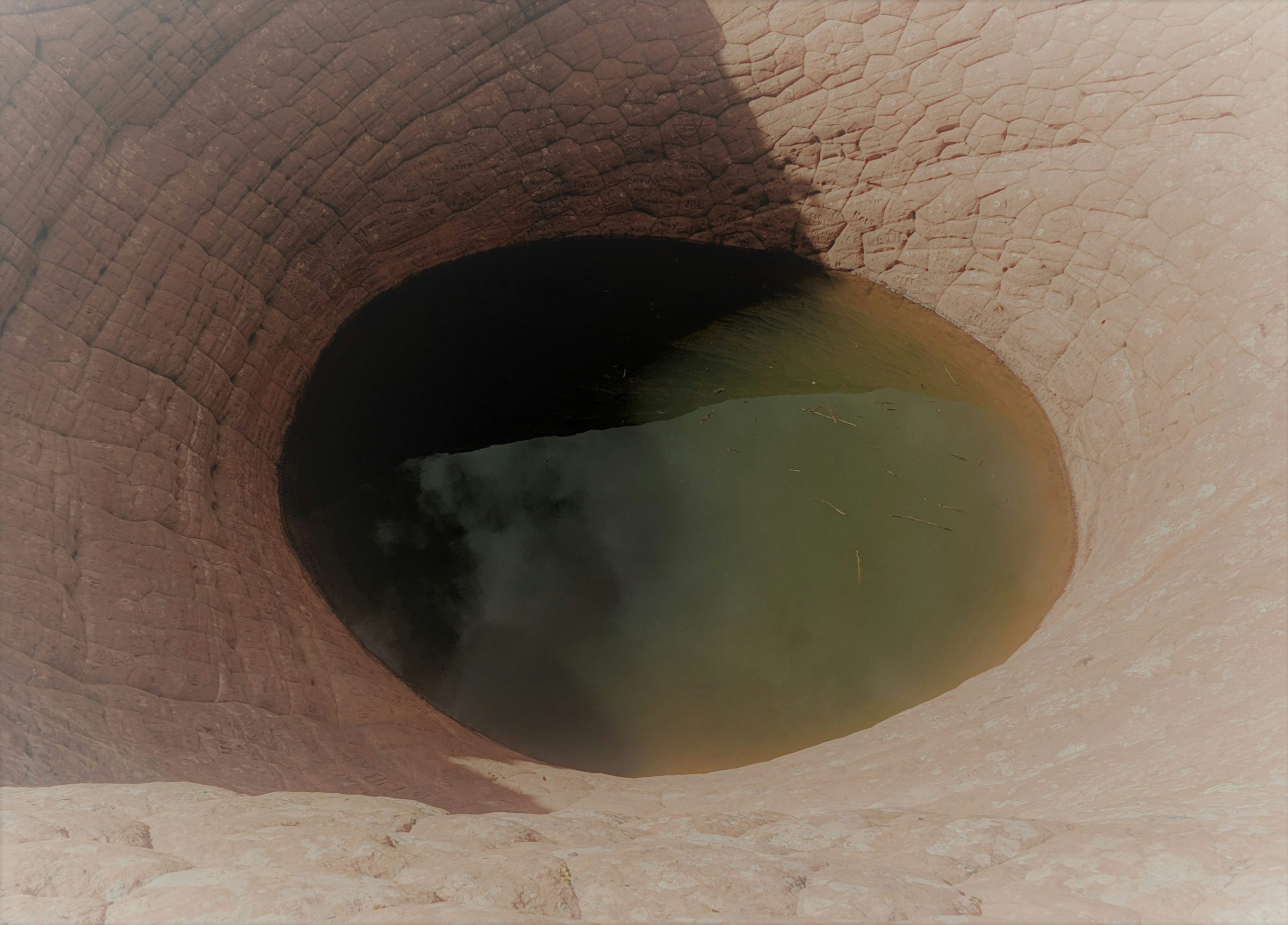

“Think of death like the abyss of a dry well. The water supply crawls further down the neck of the well with each bucket draw. Though each well-owner realizes the mortality of their reserve and that it will be depleted, we continue to draw until the water is no longer visible from the surface. Then, one day, the owner will reach so far that they will fall. The well is so dark that no one from above can see how far they will fall. But the darkness is a blessing, too, because the victims are rendered blind within the wall, so they can peacefully watch the passing of stones that mark where their water supply once reached. Your grandpa and grandma know they have a limit similar to yours. It won’t be your turn for a long, long time, though; you are still young, baby.”

I didn’t dream that night.

What if I fall in before my well dries?

In the ladies change room, my fixation on death was consumed entirely by the two-piece bathing suits from Justice my friends flaunted in front of me. There were four of us at the wave pool that day, three of us in two pieces. We each took turns drenching ourselves in the pre-pool shower as we watched parents wrestle their toddlers into impatient lineups in the pool and older kids wrestle each other over a pool noodle.

“Guys! I found rings, wanna play toss?”

Adrenaline pulsed against my forehead as I watched a ring land behind me. I followed its yellow donut shape, kicking to sink myself and scratching blindly at the tile floor until my fingers found the familiar rubber object. I grasped it and pushed off, but while my mind thought I’d broken the surface, my head remained underwater. A platform boat rested heavily on the water’s surface, just above my head. My breath lodged, and I placed my available palm against the foam platform, searching desperately for an edge. My stomach weighed me down as I realized I couldn’t find one. The muffled laughter of children above me taunted my ears, and I felt the water grow warmer around me. For a minute, I saw the well.

What if I fall?

If one drove two exits down the highway from the wave pool, they would reach Lionsgate Hospital, an institution isolated by overpriced food markets and neighbourhoods with winding entrances. I was just three when my first sister was born in that hospital. “On November fifth”, my father would tease, “all of Lionsgate would wake to the wrathful cries of three women”. Yet, each cry was hardly wrathful; they could not have been more unlike. While my mother cried of relief and I cried of envy, my sister cried of death. She cried for every strained breath she took when she wasn’t sure there was going to be a second; she cried for the venture into uncertainty. We all cried as she did once, and we’d all cry like her again, afraid of what we think is unexplored until we took our last breath. I wonder if Mao cried as she did. And as she was held, fed and pacified, I couldn’t help but think how intimate we truly were with death, with the unknown.

I woke up on the shore, flashes of a white cross upon a red background glazed over my eyes, the echoes of death still resonating within my brimming well.

Tianyue Liu is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto pursuing a specialization in chemistry and a minor in creative writing. She was born in Shanghai, China and moved to Vancouver so her parents could outrun the “one-child policy” and get busy without consequence. Ten years later, she is now the eldest of four children, so at least she can say her parents did not waste the opportunity. If not drowning in physics or the bathtub, she can be found complaining about the permanent Buddhist incense smell in her household.