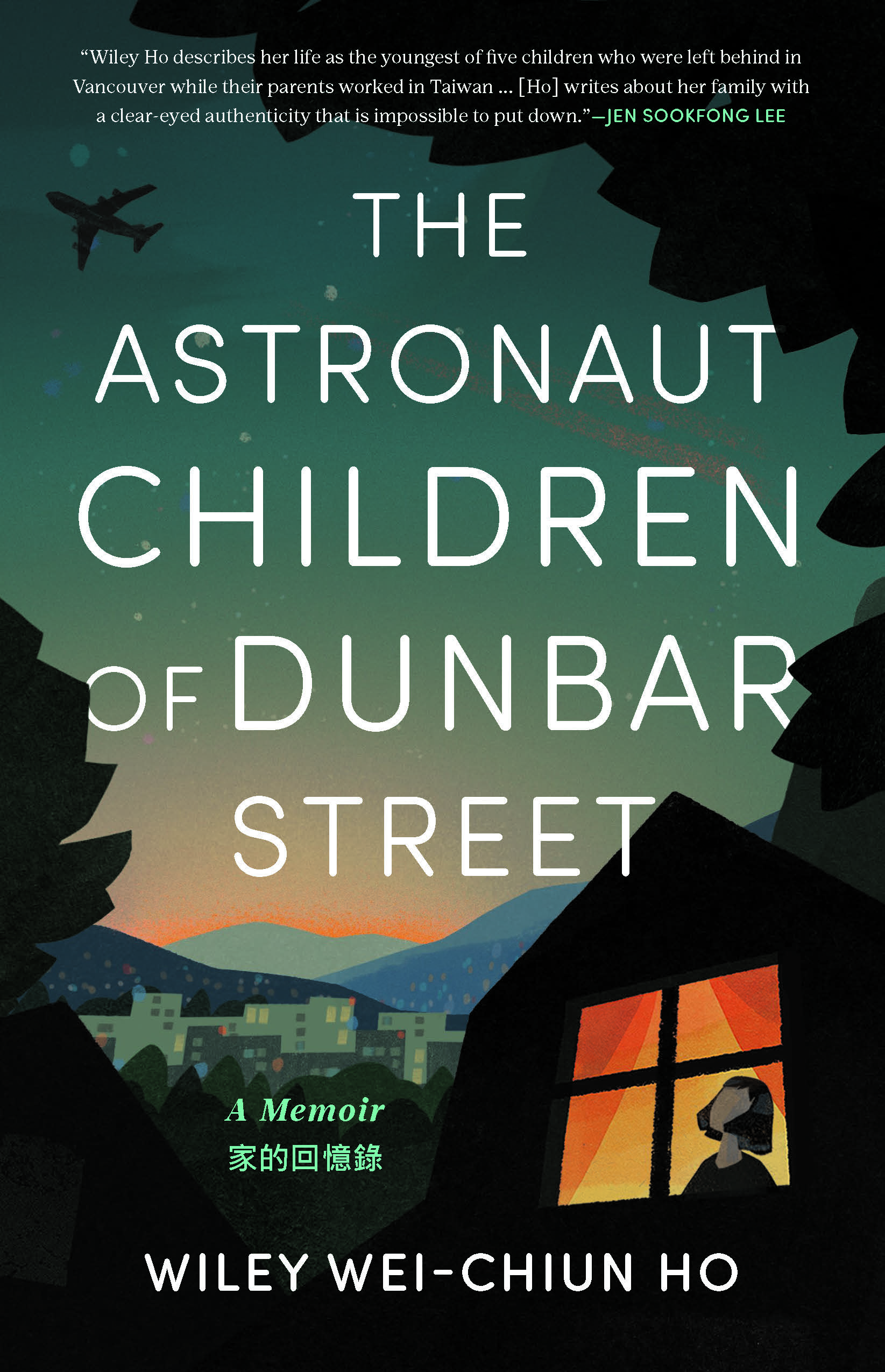

Author of the new book The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street (published by Douglas & McIntyre), set to be released in March 2026, Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho writes with sustained attention to interiority, language, and the subtle pressures of memory and place. In this excerpt, Wiley traces the contours of lived experience with clarity and restraint, allowing the personal to gesture toward broader questions of belonging, intimacy, and inheritance.

Author of the new book The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street (published by Douglas & McIntyre), set to be released in March 2026, Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho writes with sustained attention to interiority, language, and the subtle pressures of memory and place. In this excerpt, Wiley traces the contours of lived experience with clarity and restraint, allowing the personal to gesture toward broader questions of belonging, intimacy, and inheritance.

Excerpt from The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street, Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho, 2026, Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

THE ASTRONAUT CHILDREN OF DUNBAR STREET

At the airport, my family huddled awkwardly together. We were on the International Departures level, where people were coming and going in every direction. All around us were moving bodies and suitcases. My brother grabbed a cart and heaved our parents’ bags onto it, the blue-and-tan bags slumping against one another like sleeping children. Five years ago, I had watched Ma stuff our entire lives into these suitcases, fretting over what we could sacrifice for a better life in Canada. Now, my parents were crossing the Pacific again but in the opposite direction, and without us.

Baba stared at a TV screen above our heads, his hands clutching stiff new passports and Canadian Airlines tickets. The tickets were issued on carbon paper, in triplicate. Each sheet would be torn off for each leg of their trip, to Los Angeles, to Tokyo, and finally to Taipei.

Brother abruptly pushed the luggage cart toward a counter. Baba called him back, his voice uncharacteristically loud and jumpy. Ma’s eyes swam between my father and my brother, who picked up some tags at the counter and turned back with the cart. My sisters, who wouldn’t shut up in the car, were now crying softly even though they had promised they wouldn’t. I took my mother’s cue and bit my lip.

There had already been a lot of tears in the days leading up to my parents’ departure, Ma breaking down every time she gave instructions on how to prepare a meal, or that we must be sure to check the stove was turned off, to check each lock before bed, and to never, ever let strangers into the house.

“We’ll be back at Lunar New Year,” Baba said. “It’s just five months away.” I asked why not at Christmas, when school would be out, but Baba said they couldn’t leave the hospital then.

“What if Taiwan is invaded?” asked one of my smart sisters. Baba said things had calmed down a lot under the new president, Chiang Ching-kuo. Unlike his authoritarian father, who’d hated the Communists, the new president didn’t plan to fight the CCP to retake the Mainland. In fact, the reunification rhetoric had died down on both sides.

“But, if there is trouble,” Baba said, tapping their Canadian passports, “your mom and I have our safety papers.”

Brother put little tags on the luggage that showed a wineglass with the word “Fragile” on them, even though the bags held only our parents’ clothes. Baba kept leafing through the stack of air tickets, scrutinizing them like the details might suddenly decide to change on him. Ma’s face tightened and crumpled and tightened again as she gave last-minute reminders to us. I stopped listening and watched the people walking by—men in suits, a couple holding hands, a family with a shrieking baby—and wondered where they were all going. When I turned back, Ma had stopped talking and was looking directly at me. She smiled, her eyes trained on my face like she was trying to memorize it.

*

When we got back to the house, nobody rock-paper-scissored for our parents’ room like we did for the TV remote, even though we had permission to occupy it. It was a sunny room with a bright bay window that faced the big maple trees in the front yard, which were just starting to change colours. Someone pulled the curtains closed and the trees disappeared from view. After a while, we walked out of the room and closed the door, the five of us wordlessly preserving it like a shrine. Later, from the end of the hall, I could almost pretend the room didn’t exist at all.

*

Our neighbours had last names like Fraser, Macdonald, and Stong. We were now surrounded by young families and clean-cut dads who went to work in the morning and returned home before dark. On the other side of the laurel hedge were the Woodhouses, a mom, dad, two little kids, and a shaggy dog that barked when I passed their house. At the Safeway, Mrs. Woodhouse always took special interest in the contents of my basket, her eyebrows lifting in polite surprise at the cans of soup and bags of chips. She was nice, except for when she got nosy. “How is your family?” she’d ask. I’d smile the way Ma taught me. “We’re fine, thank you.”

On a weeknight, without having to check my watch, I would know it was five thirty by the sound of Mr. Woodhouse’s Volvo crunching to a stop on the gravel drive next door. Soon, smells of cooking would drift up to my second-floor bedroom window. Sometimes Mrs. Woodhouse sautéed garlic, which made my mouth water. From the other side of the high laurel hedge separating our two houses, I could hear the Woodhouse children bounce on their trampoline. When Mrs. Woodhouse called, “Kids—supper!” bare feet would thud on grass and scamper across a wooden deck. Then, the scrape of chairs being pulled back amid shrieks of juvenile energy. The tinkle of cutlery on plates. All would go quiet for a few minutes as the Woodhouses descended on their meal. This was my cue to go downstairs and rummage in the fridge for leftovers, which I’d bring back up to my room and eat on the bed so that I could eavesdrop on my neighbours.

It was the sounds of a family eating a meal together that made me the most homesick. In Mandarin, 家jiā means home and family interchangeably, the two meanings intertwined and inseparable. But in Canada, I discovered that they could be separated.