Laifong Leung in Vancouver, BC

Although Dr. Laifong Laifong retired from academic life just a few years ago, her current work continues a career that has spanned decades that includes an in-depth look into interplay of Chinese Canadian literature. Born in Guangdong, China and raised in Hong Kong, Laifong Leung received her BA from the University of Calgary, MA and Ph.D degrees from the University of British Columbia. Having taught Chinese literature, language, and calligraphy at the University of Alberta from 1985 to 2008, Laifong continued her writing in Vancouver, and continued dedicating herself to the study of contemporary Chinese literature and Chinese Canadian literature. Most recently, the University of British Columbia invited Laifong back to teach the first ever course in Hong Kong literature as part of the new Hong Kong Studies Initiative. Ricepaper magazine interviewed Laifong as part of its profile of scholars who study and teach the literature of the Asian diaspora that both influences and informs Asian Canadian writing. Laifong’s most recent book is Contemporary Chinese Fiction Writers: Biography, Bibliography and Critical Assessment which documents eighty of the most significant Chinese writers in the post-Mao period in 1976.

Can you tell us how long it took you to research and write this book? What inspired you to do this book at this time?

This is a good question. It is not an exaggeration to say that it has taken me decades to prepare for the writing of this book. Let me tell you how I entered this field of study.

In the summer of 1976, I joined a group of 18 students to China for several weeks. (Paul Yee was also in the group.) This was an eye-opening experience. It gave me a rare opportunity to see China first-hand. In those days, going to China was something extraordinary. That’s why after the trip, I was invited to show the slides to people several times. After the trip, I began to follow the news about China. Mao died on September 9, 1976. In August 1978, with the relaxation of government control, Scar Literature (or translated in Chinese as Wound Literature) emerged. The name Scar Literature comes from the tragic story “Scar” (Shanghen) by a university student named Lu Xinhua. Works exposing tragedies inflicted by the Cultural Revolution soon flooded the literary scene. I was shocked and moved by what I read. I subscribed to many literary magazines that came out of China. I did this through the Van-China Bookstore on East Hastings. I read profusely, making bibliography cards and jotting notes. This became my habit for a long time. I still follow the development of Chinese literature, though not as intense and closely as before.

I was among the first academic to teach Post-Mao fiction in Canada. In the mid-1980s, when so many works were pouring out in China every month, few were translated into English. It was frustrating. I thought I should write a book introducing the most important writers so that the students could have some idea of contemporary Chinese literature. I knew it would be a big project and at the time I was too busy to do it. In the summer of 1987, I received a bilateral exchange grant to China. Through the arrangements of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, I interviewed writers I dealt with in my doctoral dissertation The Fictional Image of Post-Mao Youth. Based on the interviews, I wrote the book Morning Sun: Interviews with Chinese Writers of the Lost Generation (M.E.Sharpe, 1994) which deals with twenty-six young writers from the Red Guard generation. This was my first attempt to introduce Chinese writers to the West. But this was just a drop in the bucket, considering the scale of the field. So I decided to take an early retirement to write this book. I had to do it in a single project because it includes a large number of writers and they are still publishing. If I did it slowly, by the time I completed the work, it would be already outdated.

I could have done it the easy way by simply and mechanically including the writer’s year and the place of birth, a selected list of important works, and briefly comment on one or two most well-known pieces. But I didn’t want to. I strongly feel that by so doing I would have oversimplified the complexities and achievements of Chinese writers, and underrated a literary era comparable to a renaissance after the disastrous Cultural Revolution. I wanted to give each writer a detailed write-up, combining biographical information with creative process, identifying major characteristics and giving a critical evaluation. I believe this will be more helpful to readers unfamiliar with Chinese literature.

Your recent work deals with Chinese writers who had connections to Canada. For example, Kang Youwei’s (1857-1927) stay in Vancouver and the Fraser Valley in the early 20th century. How did Canada influence such intellectuals and writers? Does it show in their writings?

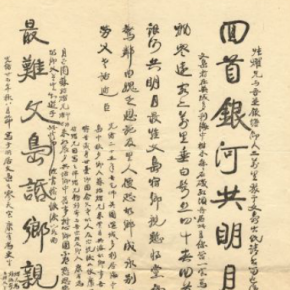

A Poem by Kang Youwei, written on Coal Island, off of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, 19 September 1899 (Courtesy of UCLA Library)

As I was about to begin with the book on contemporary Chinese fiction writers, unexpectedly, I was invited to do a different research project. The project’s overall title is “History of Literary Interactions between China and Foreign Countries”. It consists of 17 volumes. This large project was administered by two comparative literature experts, Professor Qian Linsen of Nanjing University and Professor Zhou Ning of Xiamen University. I was asked to lead the writing and editing of the volume on China and Canada. Professor Qian told me that he had been looking for a literary scholar with an overseas Chinese background. When he learned that I was born in China, grew up in Hong Kong, and from an overseas Chinese background – my grandfather came to Canada in 1918 – he was thrilled and wanted me to do the project. At first, I was reluctant because I had planned to focus my energy on Chinese writers. But hearing that he would delete Canada from the list if I didn’t do it, I was in a dilemma. Finally I agreed. I didn’t want Canada to be absent from this series.

I had three collaborators: Dr. Ma Jia from York University, Professor Zhang Yuhe from Montreal, and Ms. Pu Yazhu from Sichuan, China. The book contains four parts. Dr. Ma Jia did the part on writings in English by Chinese Canadians; Dr. Zhang dealt with Sinologists in Quebec and writing in French by Chinese Canadians; and Ms. Pu dealt with the reception of Canadian literature in China. I did the part on Sinology in Canada, and literature in Chinese and cultural activities in the Chinese community. In retrospect, I have reconstructed two histories: the history of Canadian Sinology (in English), and the history of literature and cultural activities of the Chinese community from the late 19th century to the present.

Since this was a new field of study, I had to begin with first hand material such as old newspapers, archival material, family letters, reports of clan associations, and interviews with people such as the last editor and manager of Chinese Times (Da han gong bao). As I dug into the material, I was so excited to discover things beyond my imagination. Through the material, I was convinced that the early Chinese community was actually a cultural community, not just a community of uneducated laborers, as generally assumed. From the newspaper Chinese Times, I found the names and activities of more than eleven book clubs. There were regular poetry and couplets competitions which attracted hundreds of participants. There were regular Cantonese opera performances. To my surprise, there were at least five active drama troupes throughout the first half of the 20th century!

I also found famous Chinese historical figures coming to Canada. I was thrilled to find that Kang Youwei had written more than thirty poems set in Canada. There were poems about his several visits to Harrison Hot Spring, and his recuperation from illness in Victoria. He also had a long essay commemorating the “Six gentlemen” (liu junzi) who were executed after the failure of the 100 Days Reform in 1899. Another exciting material I found was his travelogue “A Journey across Canada” (You Jianada ji). When he was invited by Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier to Ottawa, Kang took the train from Vancouver to Ottawa, describing the scenes along the way. While in Ottawa, he was warmly received and was impressed by the National Library where he came across some Chinese books. He was pleased that a young woman painter did a portrait for him. This was a valuable record of cultural interaction between a Chinese scholar/politician and the Prime Minister of Canada.

The second important Chinese intellectual was Liang Qichao (1873-1929), who visited Canada in 1903. He was Kang Youwei’s student and supporter. Liang was a Cantonese like Kang, and a native of Xinhui County, one of the Four Counties (the other three being Taishan, Enping, and Kaiping). When he arrived in Vancouver on February 6, 1903, he was received by a hundred Chinese people at the pier. He spent two months in Vancouver, giving talks and observing the life of his countrymen. As a keen social observer, he was very impressed by the use of elections by the clan associations. He also pointed out the narrow range of businesses run by the Chinese which limited their economic development. Seven sections of his book Travelogues of the New Continent (Xin dalu youji, 1903) are devoted to Chinese in British Columbia. Liang Qichao’s big contribution to the Chinese community in Canada was that he founded the first Chinese newspaper Daily News (Rixin bao) in Canada.

Your recent Chinese publication History of Literary Interactions between China and Foreign Countries: The China-Canada Volume is published in Chinese. Can you tell us more about this title? Is there any plan for an English language translation?

I do have a plan for an English translation. In fact, we were encouraged to do so by the Chinese publisher. I plan to expand the content and update the material. However, I had published an article on the early Chinese cultural activities in British Columbia Literary Interactions between China and Canada: Literary Activities in the Chinese Community from the Late Qing to the Present in the Journal of American East Asian Relations in 2013.

Your most recent book Contemporary Chinese Fiction Writers: Biography, Bibliography and Critical Assessment documents eighty of the most significant writers of the post-Mao period. this generation. Can you tell us why the number eighty?

After Mao’s death in 1976, a large number of exiled writers returned to the literary scene. The most notable were the “rightist” writers condemned in the 1957 Anti-Rightist Campaign who were sent “down under” for twenty years. A larger group entering the literary scene were former sent-down youths by the Rustication Movement from 1968 to the late 1970s. Now back to their city homes, they wrote about their disillusionment and their horrible experiences. In addition, there were writers from the army, factory, and other sectors of society. Because the backgrounds of Chinese writers are so diverse, so are the topics of their writing. A partial list will include Scar literature, Reform literature, Root-seeking literature, Feminist literature, New realist literature, Science fiction, Avant-garde literature, Historical fiction, Spy literature, and many more.

The number eighty did not have a special significance. I had planned to write a few more when, at the last stage, I read in the newspaper in August 2015 that Liu Cixin became the first Asian writer to win the Hugo Award for Best Novel in the United States with The Three-body Problem (in Chinese called Santi). I knew I had to include him. To include him, I would have to read Chinese science fiction and update myself in the genre. This took up the remaining time given to me by the publisher. If I had been given a few more months, I would have included those few more I had planned and wanted to include.

While a handful of writers are well known in the West, such as Ha Jin or even Mo Yan, the majority of Chinese writers are relatively unknown outside of China. Why is that? Who are some writers that we should learn more about in the West?

To be honest, very few Chinese writers from China are known in the West. If you ask a professor of literature in any university in Canada to say the names of Chinese writers, I dare say, only a handful, maybe even fewer, could list a few names. But if you ask any professor of literature in any university in China to mention writers from the West, they could list a dozen or more without hesitation. There is a clear imbalance here. Why? There are complex reasons, historical, political, and economic. One aim of my book is to introduce significant writers to western readers, get people know about them and their writings, and hopefully, this will guide potential translators. To understand the culture of a country, the most affordable and direct way is to read the literature of that country. Fiction is a genre that can provide the most information about a people. Readers can gain a lot by reading the writers’ lives, their stories and how they come to write their stories.

You are going to be teaching a course at UBC about Hong Kong literature. Can you tell us more about this course? What are some authors and course readings that you will have as part of the course?

I am honored to have the opportunity to teach this course. As far as I know, this is the first time that Hong Kong literature is being offered in any Canadian university. I am still in the middle of preparing for this course. All I can tell you at this stage is that I will cover the historical development of Hong Kong literature, and discuss its connection with the literatures of Mainland China, Taiwan, and overseas Chinese communities. I will deal with both the “highbrow” and “popular” literature. Writers such as Liu Yichang, Xixi, Li Bihua, Ye Si, and Jin Yong, will be in the course. If time allows, I will include works in English too.

Recently, with the Umbrella Movement and the removal of Hong Kong’s city councillors due to controversies over their backgrounds, there is a lot of tension in the city. Can you tell us more about the situation in Hong Kong in relations to literature and culture?

The Umbrella Movement really was an unprecedented event in Hong Kong. It involves far more people than the riot in 1967. Moreover, most were young people. Their participation was, I think, a sign of social discontent, not just an expression of political protest. As a distant observer, I think the movement may have a positive impact on the social consciousness of the young people. They may become more attentive to issues that affect their future, and Hong Kong’s future. As for the “sworn in” issue of those few elected councillors, I am afraid I don’t agree with their way of expression.

There are enough worries for cultural people especially after the Causeway Bay Bookstore incident. I am worried more about self-censorship than actual orders from above. This is harmful to artistic creation.

There has been a strong connection of literary writers who lived between Vancouver and Hong Kong. For example, Chinese language writers such as Yi Shu (Isabel Nee, 亦舒) lived in Vancouver and had based some of her stories in this city and the West. How can we see these writers as part of the diaspora, rather that just part of the city?

Since the early 1980s, more and more Hong Kong people had chosen to emigrate, and Vancouver, a city on the Pacific Coast, naturally became their favorite destination. Yishu was already a famous writer in Hong Kong before she came to Vancouver in 1991. I found at least two of her novels, namely Not Easy to Live Here (Buyiju, 1996) and Roaming the Four Seas (Songheng sihai, 2009) are about overseas Chinese. The former is about two young women from Shanghai living in Vancouver: one becomes a strip dancer and is killed by gangsters, and the other resists temptation, works as a tutor for three children, and focuses on her study. The latter, set in the early twentieth century, involves two lovers, and the hero’s two encounters with Sun Yat-Sen. Both novels depart from the author’s numerous popular works. Like most ethnic Chinese writers writing in Chinese, their readership is mainly in the Chinese-speaking Mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong and elsewhere. Still, no matter how famous they are in the Chinese speaking world, without translation, they remain an unknown entity in English and French-speaking Canada.

Are there any Chinese authors based in Vancouver who write for Chinese audiences back in China, Taiwan, or Hong Kong? Are there any you would particularly recommend?

Yes, there are a large number of Chinese authors writing in Chinese and publishing their works in the Mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. They also publish on the web. In the Chinese Canadian Writers Association, which I was initiator and co-founder in 1987, there are quite a few writers who publish novels, short stories, poetry and essays regularly. I would like to mention a few. For instance, those who write poetry include Qing Yang and Yu Xiu from Shanghai, and Han Mu from Macau; those who write novels include William Chan from Hong Kong, and Yuping Li from Foshan, Guangdong province; and those who write essays include Ji Yu from Taiwan, and Ruo Zhi from Hong Kong; those who write children’s literature include Ah Nong and Wahying Chan, both from Hong Kong.