In Sundry Languages

The experimental “In Sundry Languages” proudly proclaims itself as a multilingual drama that requires no translation. The director, Art Babayants, trusts his audience to be able to appreciate the show without fully understanding it. The show’s characters often embody attempts at communication and learning so genuinely that language might be rendered unnecessary. The play features a diverse group of performers whose linguistic and cultural backgrounds range from Chinese, Arabic, Portuguese, English, Russian, to Spanish. It combines vignettes written by the performers, who draw on their personal experiences as immigrants, residents or refugees in Canada for inspiration.

For example, the story of a clash between an Anglophone driver and a francophone customer points sharply to the indispensable role of multilingualism or that of translation, without which two people from different backgrounds would fail to communicate. The story of a Chinese immigrant girl (performed by Angela Sun) who has to apologize for her mother tongue alludes to a popular cultural phenomenon within Chinese immigrant communities – losing the ability to converse in Mandarin Chinese also means losing touch with Chinese tradition, identity, and cultural memory.

However, the scenes themed around “Where are you really from?” were the ones that further explored the waning identity of the immigrants in Canada by prompting the audience to ask the question repeatedly. Each scene sparks four exchanges between two hypothetical neighbors living in Canada. The dialogue begins with one neighbor asking the other, “Where are you from?” The answer is “here”. The first neighbor asks: “No, I mean where are you from?” The other replies: “North York.” That is hardly what he wants to hear, prompting him to pursue the inquiry further: “I mean where are you really from?” Eventually, one (Angela Sun’s character) spells out the answer: “China…town….” Then the light fades out.

Where are you really from? -China…town…

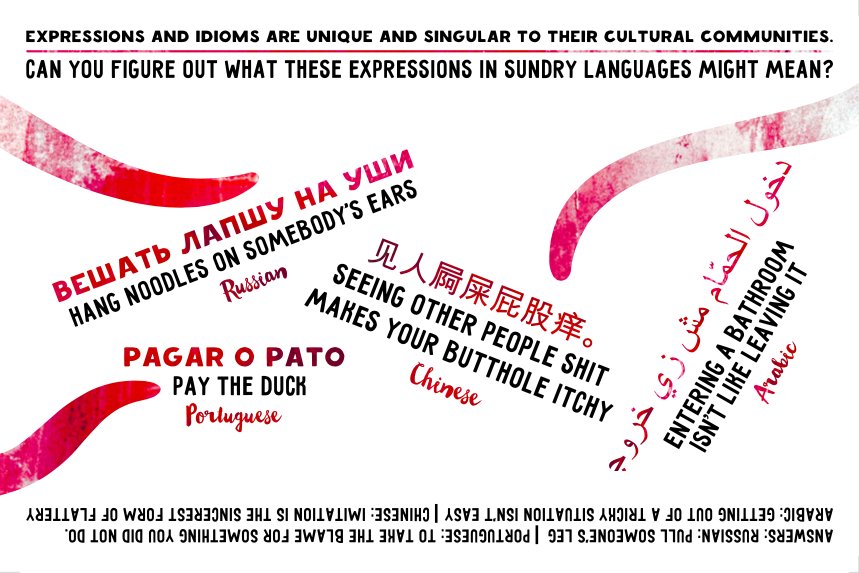

Some other stories are performed in Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian. While not knowing these languages might pose difficulties to fully understanding the scenes, especially to monolingual audience members, it is also the beauty of the play. In the absence of translation, the audience deals with the foreignness in different ways. Most “surrender” themselves to the foreignness by trying to appreciate it from afar (See Debra Caplan, 2015). Other strategies can be to admit the fact that literal translation is not required: abstraction and imagination suffice to capture the affective level of the show. One can also argue that a true intercultural communication is not possible, and one just needs to succumb to the gap that exists. (ibid.)

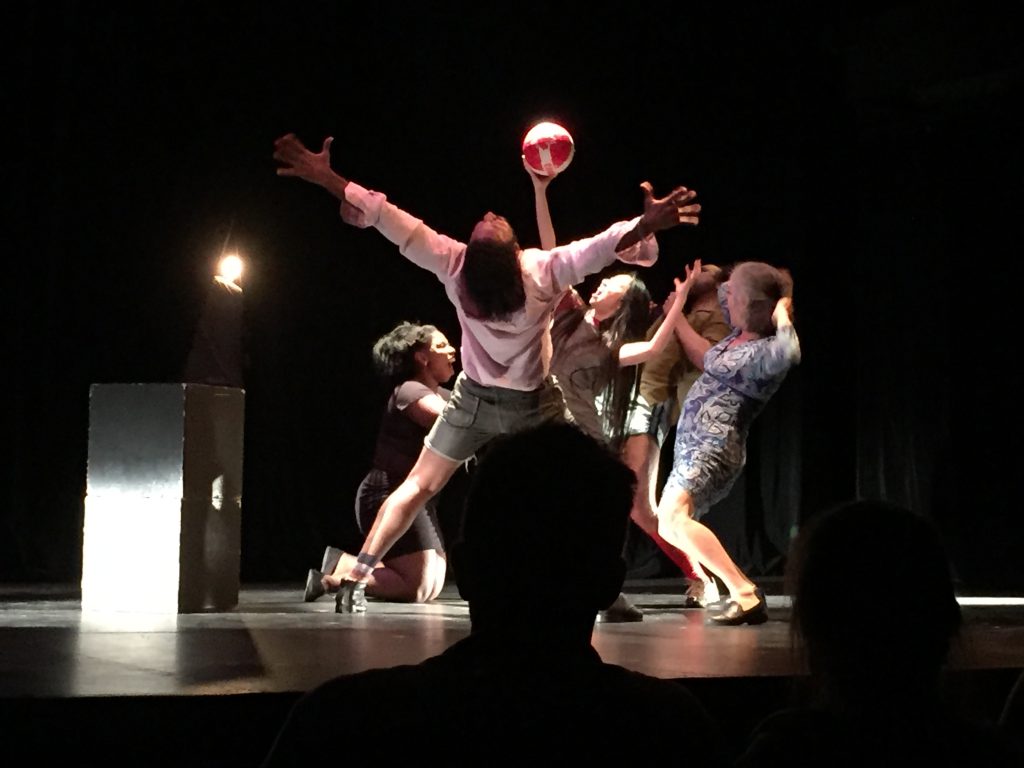

In spite of the difficulties of living in a multilingual community, “In Sundry Languages” inspires by offering extensive possibilities of challenging them. The play explores the interplay between body and language, which might foster a better understanding of one’s self and the people one interacts with alongside their linguistic and cultural identity. As Gerd Brauer points out in his book Body and Language: Intercultural learning through drama, a physio-intellectual aspect of the mind is important in feeling, communicating, and living in a physical space — particularly in a multilingual community — but it is frequently overlooked in traditional Western education. The play shows that focusing on linguistic signs and signals alone is not enough in interlingual and intercultural learning, whether in arts, mathematics, or history. Embodied language is equally important, and this incorporates the physical experience of walking and talking. Communication is not conducted solely via language, but also through physical movements. A second helpful way of living within multilingualism is by showing sincerity and genuineness. Under the comedic surface is a sense of struggle which is met by a contravening force of attentiveness to learn and correct. Despite the huge language barriers, the play’s characters struggled to be understood, however using various body gestures. Their ferocity and frustration that often surfaced after another failed attempt to communicate indicates a sense of sincerity.

In spite of the difficulties of living in a multilingual community, “In Sundry Languages” inspires by offering extensive possibilities of challenging them. The play explores the interplay between body and language, which might foster a better understanding of one’s self and the people one interacts with alongside their linguistic and cultural identity. As Gerd Brauer points out in his book Body and Language: Intercultural learning through drama, a physio-intellectual aspect of the mind is important in feeling, communicating, and living in a physical space — particularly in a multilingual community — but it is frequently overlooked in traditional Western education. The play shows that focusing on linguistic signs and signals alone is not enough in interlingual and intercultural learning, whether in arts, mathematics, or history. Embodied language is equally important, and this incorporates the physical experience of walking and talking. Communication is not conducted solely via language, but also through physical movements. A second helpful way of living within multilingualism is by showing sincerity and genuineness. Under the comedic surface is a sense of struggle which is met by a contravening force of attentiveness to learn and correct. Despite the huge language barriers, the play’s characters struggled to be understood, however using various body gestures. Their ferocity and frustration that often surfaced after another failed attempt to communicate indicates a sense of sincerity.

The use of cameras in the performance is a peculiar yet bold move. While capturing the physical struggles demonstrated by the characters in the play, the camera enlarges aspects the performers’ bodies which oddly conflict with our expectations. For example, the camera would capture the performer’s hand instead of her mouth while she was reciting her monologue. In other scenes, the camera zooms in the performer’s teeth. When asked about this oddness, Babayants explained that it was about showing what is left out. By drawing the audience’s attention to minor details of the body, this can make us reflect on minority voices in language and culture, which ought to be heard. The reinforcement and empowerment of minority voices is realized by the second role of the camera which he terms “freedom of choosing.” The audience makes a choice whether to look at the camera or at the actors on stage. Allegorically, “freedom of choosing” is implemented by both majority voices and minority ones. It adds to complexity of multilingualism and multiculturalism by making it more diverse – one can choose how to communicate and who to communicate with. “Freedom of choosing” also liberates minority languages and cultures by rendering both the majority and minority groups in equal terms. Freedom precedes equality, which could lead to true interlingual and intercultural communications.

“In Sundry Languages” abuses various cultural references and accents, which are often peppered with sarcasm and humor, and presents the dichotomy of living in a multilingual community. Despite difficulties of living within multiculturalism – such as failure to communicate and loss of cultural identity, such difficulties could be reduced by a sense of genuineness to learn, and a liberated way of communicating. It is a play of possibilities and imagination that inspires second-language learners, educators, and everyone who lives within multilingualism and multiculturalism.

**

Interview with Art Babayants:

1. What propelled you to produce “In Sundry Languages?” What is your experience related to language and cultural identity?

I’ve never lived in a culture or country where my ethnicity or heritage represented the dominant majority, so I can easily relate to the minoritarian issues, linguistic or cultural, portrayed in our production. I must add though that I also have a very difficult relationship with the Armenian language, my mother’s tongue (yes, mother’s, not mother). Sadly, I don’t speak it well enough to have a complex conversation in it. In fact, my third language, English, is currently my strongest language and I feel most comfortable when I express myself in that language. Overall, while I am living my life literally “In sundry languages”, I may relate to my first, second, third and fourth languages differently and not necessarily in the ways the ISL characters relate to their own languages.

2. Why was there no translation in the play? To what extent does the translation ruin the “presence” of a performance?

It started as a creative experiment: is it possible to develop a dramaturgy that doesn’t always yearn for translation? Translation gives you direct access to meaning but that meaning is always skewed, it’s never the same as it is in the original language or culture. In a way, translation gives one an illusion of full access. But what happens when we don’t hide the fact that things are not really translatable? What strategies would the audience develop to still understand what is happening on stage? Would they give up altogether? Is there a way to create a dramaturgy complex enough so that the absence of translation doesn’t induce immediate boredom? These are the questions we are struggling with as co-creators of “In Sundry Languages.” The other reason why there is no translation is reclaiming power from the anglophone majority. Those who speak languages other than English, specifically non-native English speakers, which make up roughly half of the Toronto population, are given more access to meaning than those who speak English only. In a way, theatre becomes a utopian space where the power (in this case the power of the official language) is subverted.

3. Your doctoral dissertation looks at the phenomenology of multilingual acting and spectating. Can you tell us a little about this topic, particularly how this is applied and indicated in “In Sundry Languages?”

My interest was to see how multilingual actors approach performance in their first language(s) vs their second (or third) language(s), as well as any language(s) they don`t speak at all. All the “In Sundry Languages” performers were given an opportunity to perform in multiple languages including those tongues they didn’t not speak very well. This is a very unusual case for Toronto theatre, I believe. In terms of audience, we made a huge effort to reach out to various linguistic and cultural communities in order to attract multilingual speakers to the theatre. What I discovered was that when “In Sundry Languages” is being performed to a truly multilingual and multicultural audience representative of Toronto, it creates a very particular dynamic: the audience doesn’t react as one entity to what is happening on stage. In fact, their reaction is always out of sync with each other, it travels from one part of the theatre to another. For instance, those who understand French react more strongly to the French scenes or jokes, those who speak Arabic, respond to the Arabic lines, while others may be puzzled why those specific lines are creating such a strong reaction. And every single night is different depending on the linguistic makeup of the audience. There is never any uniformity in their reactions, which I think makes “In Sundry Languages” rather unique.

4. You are also interested in integrating acting and second language teaching as is indicated in your various theatre projects since 1997. What is your suggestion for the second language learners and educators?

Speaking any language is a little bit like performing; also, it doesn’t just happen in your brain or in your mouth. Language involves your full body. I do recommend exploring how gesture, body, facial expressions partake in the whole process of learning and speaking a second language. If you do so, you may encounter a lot of interesting challenges but you may also discover new parts of your own personality that you never thought existed. It’s a fascinating process.

I base my review on the performance of “In Sundry Languages,” on July 11th, 2017. I would like to thank all the producers, performers, and Toronto Fringe Festivals’ volunteers, without whom the show could not run smoothly. I owe my gratitude particularly to Art Babayants, Henry Heng Lu, and Angela Sun, for their help with this interview, and Christina Kindl who kindly greeted me before the show.