I first heard of Calgary musician FOONYAP from editor/author friend Jen Frankel who had attended FOONYAP’s concert in Guelph as part of the Kazoo! Concert Series and told me I really had to interview her. FOONYAP’s debut full-length album Palimpsest had been released in October 2016 to much critical acclaim, drawing comparisons to Björk, described by CBC as “a stunning, colossal work that’s as disconcerting as it is captivating” and was named #6 in the 2016 Top 30 Albums of The Year by the Toronto Star. Palimpsest also made it on the Polaris Music Prize Longer List in 2017. Polaris is a music award annually given to the best full-length Canadian album based on artistic merit, regardless of genre, sales, or record label.

In an interview with the Asian Heritage Foundation, FOONYAP talks about struggling to be a female independent thinker while growing up in the patriarchies of Catholicism, traditional Chinese culture, and classical music. FOONYAP started violin lessons at the young age of four, entering the Mount Royal Conservatory of Music by at age eleven. When she was young, she muted her desire to be an artist because the family disapproved. However, she was also enrolled in the conservatory for classical violin and expected to excel.

FOONYAP’s story struck a chord with me because similar to hers; I had a desire to be a writer but was told I would starve to death. Read books, but make a living in a more “safe” occupation. Her story is the story of many immigrant/next generation Asian children in North America and abroad.

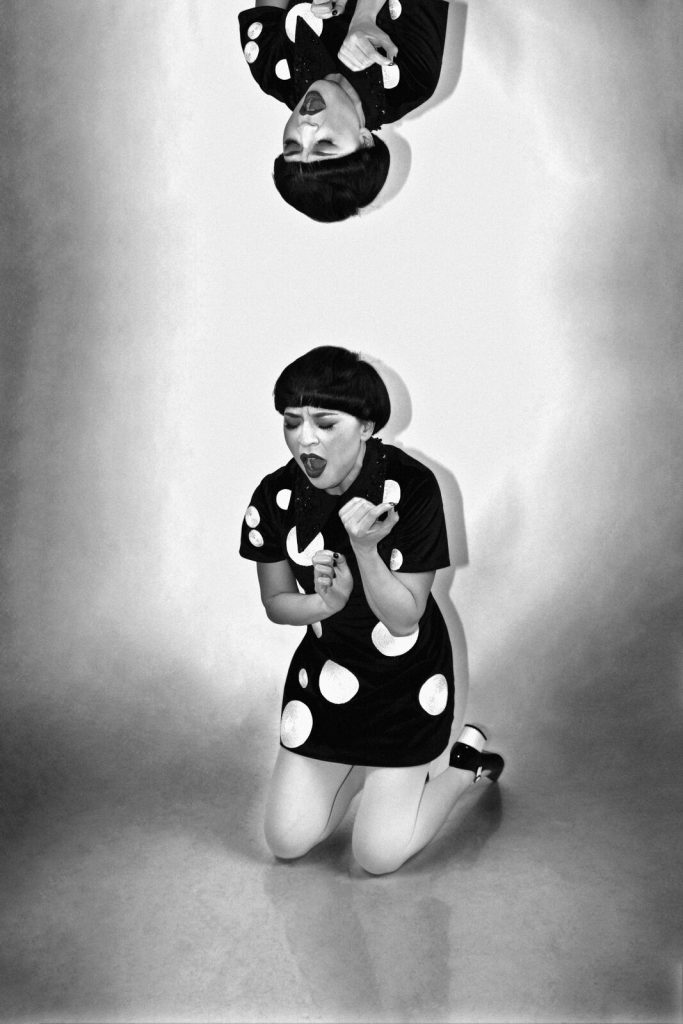

In February 2018, FOONYAP gave a series of concerts around Ontario and that’s when I caught up with her.

JF Garrard (JFG): Thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us at Ricepaper Magazine! Your story really resonates with a lot of us who are attempting to build careers in the arts. In the Asian Heritage Foundation interview, it was mentioned that you had a day job and then quit to pursue music. Where were you working and what was the catalyst for leaving it to take your artistic leap?

FOONYAP (F): I worked in the non-profit sector. For various reasons, it became clear my position was no longer a good fit. Concurrently, ‘Palimpsest’ was gathering momentum in the press. I knew that the time was ripe for me to take the risk.

JFG: Your name is FOONYAP – what does it mean and why did you choose this name versus picking a more “Westernized” stage name?

F: FOONYAP is the union between a part of my Chinese middle-name and Hakka surname. Easily pronounceable in English, it presents my Asian Canadian heritage in a mononymous stroke. I was inspired by Chinese calligraphy, in which the way a word looks is just as important as its meaning. Every time you see FOONYAP on a page, you witness my artistic statement.

JFG: Your album Palimpsest was a therapeutic reconciliation with your sheltered Chinese-Catholic heritage and the intense classical music training of your childhood. Can you describe a little bit about what memories you were thinking about when you wrote the music?

F: I actually drew a web comic about my specific experiences that inspired the album. To summarize, I was processing the overwhelming guilt and shame I felt for disappointing my family.

The collectivism of traditional Asian cultures creates a context in which one’s actions reflect not only upon oneself, but one’s family. Strong emotions, especially by a female of a younger generation, are not tolerated and one learns to hide their inner desires that would disrupt group cohesion. One also learns to excel at any cost, bringing honour to the family. I found that the classical music world and Catholicism, with their rigid guidelines for what they deem socially-acceptable, reinforced the collectivism I grew up.

Not only did I fail as a classical violinist, I dropped out of high school and developed a mental illness. It took me a long time to ask for help because I felt like admitting something was wrong would have reflected poorly upon my parents. I felt ashamed- no one else in my family struggled, what was wrong with me? Why was it so difficult for me to just do what was expected, and not cause my family undue stress?

It has taken me a long time to embrace this artist-self that was unacceptable to these patriarchal authoritarian systems.

JFG: After participating in so many festivals, do you feel any pressure as a female, Asian musician given so few are on center stage?

F: No. Sharing this project has taught me how universal pain can be. People from all backgrounds relate to my work and I believe that our struggles connect us.

JFG: What has been the most thrilling moment of your musical journey?

F: So much of my life is spent in the past and the future. When I’m on stage, nothing else matters. I can sense when the audience is with me in the present; when we’re all feeling together and savoring the totality of our shared human experience.

JFG: In an interview with the CBC about music that reminds one of Canada, you mention that “Canadahood” is a dream. What do you mean by that?

F: Canada and ‘nationhood’ only exists in the minds of humans, manifested in the physical world. I don’t think we can escape the myths we construct for ourselves, but I think it’s important to acknowledge how real they are and question which ones are worth protecting. We must remember ‘Canada’ is the stories we tell about it, think about who gets to do the telling, and not get so defensive when the stories change.

JFG: Your presence on the internet, social media and Canadian music scene has been expanding since your 2016 debut album. Are your parents proud of your creative accomplishments now? Have they attended any of your concerts?

F: Yes! My family is extremely supportive of my career. In spite of the sensitive material, they feel my success is theirs.

JFG: After creating Palimpsest, what have you learned and what will you be applying to your next album?

F: A ‘palimpsest’ is a manuscript in which traces of the original can still be found. I’ve learned that I must build my sense of self from my struggles and rewrite my own way forward.

Sharing my work with audiences all over the world has also taught me that the isolation of suffering is an illusion and that our emotions connect us to one another. For my next album, I’m fearful of what I would rather leave unsaid, but I now know that others are probably feeling it too.

JFG: Do you have any advice to Asian peers who want to follow the road to become an artist but are afraid?

F: Your family may never understand or approve of your work and that is okay. Learn how to set healthy boundaries.

Fear is normal. Allow yourself to feel afraid. Great art is made by those who feel afraid but do it anyway.

JFG: Thank you again for taking the time to let our readers learn more about you and best of luck on your journey as an artist!

For more information about Foonyap’s music and the latest news about her, please visit her website – FOONYAP.COM.