‘DOB in The Strange Forest (Blue DOB)’, 1999

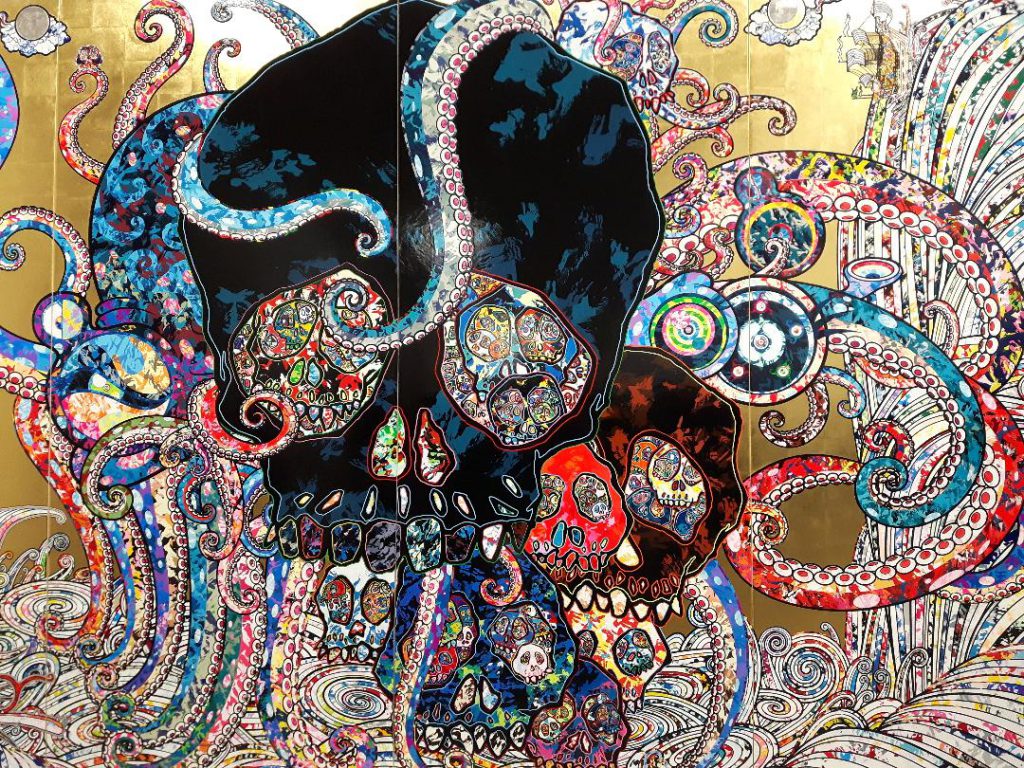

Walking into Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg is to step into a phantasmagoria of the garishly cute, the disarmingly grotesque, and above all, the unflinchingly bizarre: vibrant, multi-eyed mushrooms sprout from the ground (DOB in The Strange Forest (Blue DOB), 1999); gremlin-like Arhats pose along the walls, stretching from floor to ceiling (100 Arhats, 2013); and misshapen skulls peek out from other skulls, creating almost kaleidoscopic patterns within their sockets (Waterfall Appears in the Ocean! In Its Midst, Kraken!, 2018). The first retrospective of Murakami to be presented in Canada, the title is derived from the Japanese adage tako ga jibun no ashi wo kurau: in times of duress, one must resort to extreme measures in order to survive; the octopus will eat itself, but it does so expecting that its tentacle will grow back.

‘727’, 1996

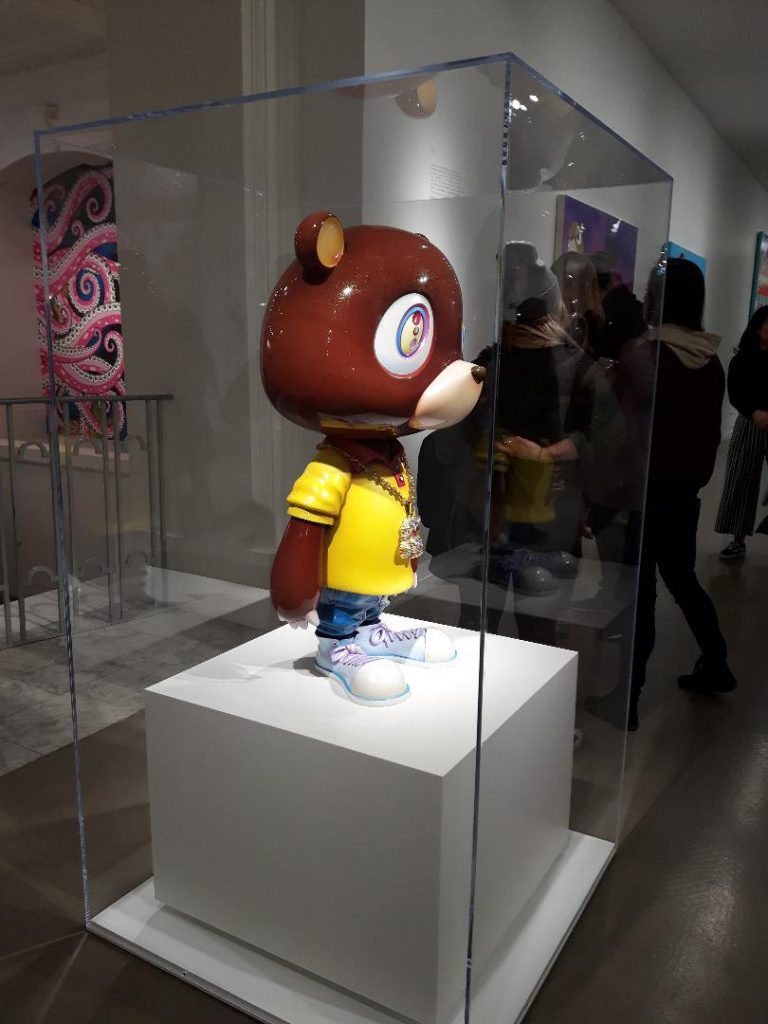

And indeed, there is much to suggest a sort of repeated cultural regeneration in this exhibition, which includes over fifty paintings and installations, some of which have never been displayed until now—new tentacles that have emerged from the various sociopolitical concerns spanning Murakami’s three-decade long career. We start with his nihonga-influenced paintings of the early ’80s: murkier, muted pieces that capture the ongoing, pervasive fears of nuclear power since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Murakami’s dissatisfaction with the limitations to which he felt nihonga could reflect everyday Japanese life, however, is charted in the exhibition’s stylistic transition into the bold lines and even bolder patterns in which many Japanese pop culture icons are rendered. The late ’90s witnessed Murakami’s conception of the postmodern art movement Superflat, which conflates highbrow art with the highly commercialized otaku subculture in a distinctive, flattened style. This period gave rise to the work that Murakami is perhaps most renowned for and demonstrates his cognizance of his increasing involvement in Eastern/Western consumerist and celebrity cultures. Such works include 727, 1996, showcasing the iconic Mr. DOB, and Kanye Bear, 2009, the statue of a character he designed for Kanye West’s “Good Morning” music video.

And indeed, there is much to suggest a sort of repeated cultural regeneration in this exhibition, which includes over fifty paintings and installations, some of which have never been displayed until now—new tentacles that have emerged from the various sociopolitical concerns spanning Murakami’s three-decade long career.

‘Kanye Bear’, 2009

In the last decade, Murakami’s style has taken on a more sombre tone in the aftermath of the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami in 2011, drawing on Buddhist folklore in an attempt to reconcile the depths of human tragedy with the possibility of recovery and reclamation. Despite this change in aesthetic, much of the artwork possesses a frenzied, proliferative quality to it, as if challenging the capacity for which something can be regenerated yet still act as a seamless substitution for the original. (Even Murakami’s methods of producing these pieces embodies, to a certain degree, this manic propagation; his art studio, Kaikai Kiki Company Ltd., operates much like a factory, employing several assistants to assemble the artwork, and is extensively involved in its commercial promotion.) The excessive repetition of painted and sculpted elements is what transmutes, upon closer glance, the most endearing cartoon into a demented monster, with several warped expressions attesting to the fact: these times that often invoke so much anxiety have forced us into an overconsumption of ourselves and an overproduction of what we desire to be familiar—and yet in this desire turns out to be deeply abnormal. Perhaps an important caveat to the Japanese adage would be that each regenerated tentacle will never be exactly the same as the last.

‘Waterfall Appears in the Ocean! In Its Midst, Kraken!’, 2018

Maybe, too, this is not necessarily bad if instead of continuously seeking the familiar we choose to embrace the change, the innovation. Murakami has stated that the title of the exhibition refers to his apprehension about his lack of imagination—how he must constantly recycle ideas to produce the material that will allow him to survive as an artist. However, his interpretations and reinterpretations of the matters that plague contemporary history produce a chaos that is fresh and entirely his own. His frantic work suggests a desire not for mere reiteration in regeneration but a reinvention to continue onward in a manner that is no longer contingent on sheer survival, but on living in the most wholesome way possible.

Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg can be seen at the Vancouver Art Gallery until May 6, 2018. The exhibition is in collaboration with Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, curated by Michael Darling.