It is 34 years after 1984 and 71 years after the 1947 partition of India. It is nearly impossible to articulate the pain of 1984 with its complex trauma, but playwright and director Paneet Singh carefully manages this by bringing the audience into a 1980s diasporic Sikh Punjabi home in South Vancouver with a strong and committed cast (Arshdeep Purba, Gunjan Kundhal, Parm Soor, and Lou Ticzon), each of whom had exquisite monologues that flowed together. The first run of A Vancouver Guldasta, part of the South Asian Canadian History Association’s (SACHA) Vancouver 2017 program, was sold out. For those of us lucky enough to have seen it, we know that Singh is a rising star in theatre. Be sure not to miss its second run of what promises to be a Canadian classic, running until October 21st at The Cultch, presented by the SACHA in partnership with Diwali in BC.

Our review begins with individual meditations on the play, followed by a co-written and critical reflection, webbed and twined from the rich threads of our conversation.

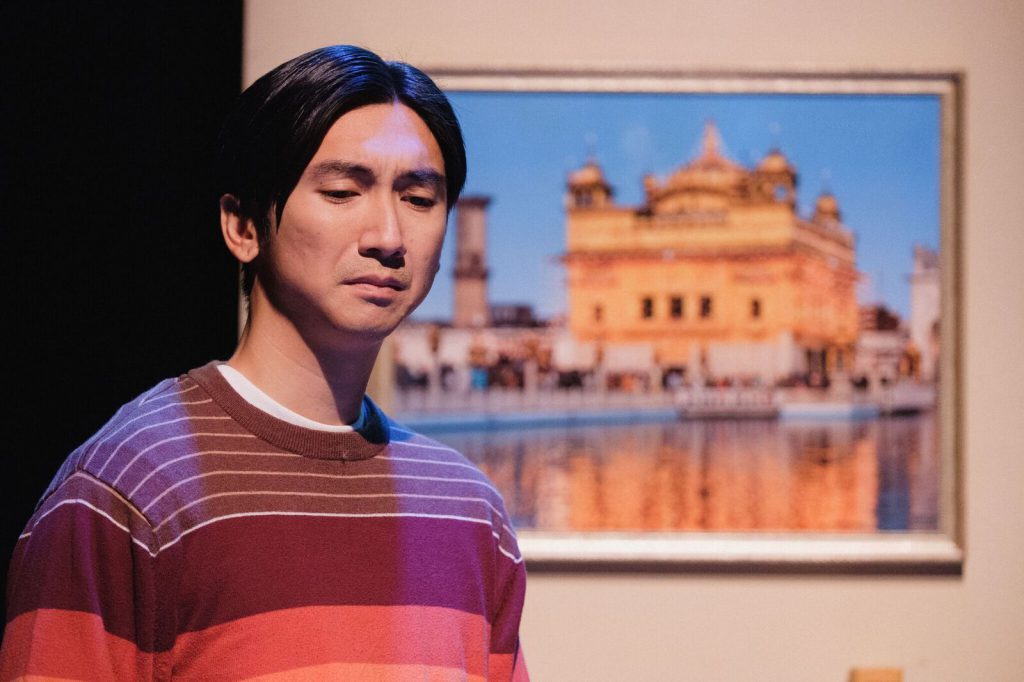

Image courtesy of Pardeep Singh Photography

KC

I watched Andy point a gun made with his hand to Rani’s head, attempting to express a small fraction of the pain swelling inside of him. Rani had asked him, repeatedly, why he didn’t stand up for himself at school; why, when others bullied him because of the way he spoke English or his eyes or his nose, he said nothing. He told her about what it meant to leave Vietnam in pursuit of safety—to leave everything behind in the hope of respite from the banality of violence. He told Rani that everyday, he chose what he could respond to, what he had the energy for. But the kind of violence he faced at school does not affect his physical safety and it was not worth risking that for anything.

My mother left China during the Cultural Revolution, originally moving to Taiwan and later to the United States. I could only ever glean snippets of the racism she faced when she casually told me about incidents. It took me years to understand why she never responded to strangers who asked “Do you speak English?” the spray painted slurs on the garage, or other instances of racial violence. She reminded me that she protected herself and her children—mixed kids who sometimes get read as white, sliding in in-betweens. If I’ve moved somewhere, she asks me if I’ve yet assimilated. To assimilate is to survive, to keep your head down, to be unnoticeable. From Leanne Simpson, “that’s item number one: make sure you’re alive. Make sure you’re not dead.”

In that moment, I was almost sure I was the only East Asian in the room. And I sat silently, as if my innards were displayed on that living room floor although almost no one could possibly know this. My Chinese-ness was so often hidden, somewhere between being tucked away and covertly protected by my mother. In that moment all I wanted to do was desperately call out: I hear you, Andy, and how much it pains me that you probably cannot see me; an inheritance and intention by my mother, a woman who knows how to strategize in a world not made for her.

Image courtesy of Pardeep Singh Photography

KS

I walked in and I was overwhelmed by familiarity. There was something uncanny about my past being historicized via the set of Singh’s play—the living room was a character in itself, convincing and uncaricatured. It was as if they found someone who had preserved their living room for 30 odd years. Here were the living rooms of my childhood: Punjabi 1980s, the living rooms I crawled around in, wandered through—the touch of brown velvet upholstery, brick fireplaces with brass fireplace tool sets, gold-gilded frames of Baba Nanak, Sri Harmandir Sahib, and images of places I had never been to made familiar, in a living room template that one could find from Ladner to Richmond to Surrey to Vancouver’s Main Street as we wove across the cities visiting people from back home, people who had helped us to come here, or the children/aunts/sisters/grandparents/cousins of those people. We went to see sick people and old people, newborns, and first birthdays. I was invited in to greet a familiar past, which I hadn’t realized was a collective one in the wide community of Sikh Punjabis in BC. Our circuitry is shown in the way we set up our homes, the living room an entrypoint to connection and conversation.

I wanted to see A Vancouver Guldasta because it offered the closest thing to a representation of my upbringing, growing up in a world where you were defined by others through a place that you had never been to, and where you connected most with the other people of colour around you, namely South Asian and East Asian communities, but also where the expectations of your assimilation into Canadian culture was to refuse your otherness and that of those around you.

I invited my friend Kristi because it was exhilarating to see a play where whiteness was not the pivot point, and our identities were represented through diasporic South and East Asian youth. Kristi sat on the floor across from me. It was strange to silently sit in a living room and watch anger and sadness flood it, unable to soothe each other or say anything. This brought me back to the tensions of my childhood, listening to things that I couldn’t quite understand by the nature of my shoddy Punjabi or my inability to grasp complex concepts. Our living rooms were lived in. They were filled articulations of stress and sadness, collective joy, and difficult conversations. In Vancouver’s political climate, dare I say, they were one of the few safe places for our social and cultural gatherings, for our heartaches and transactions, where collective moments, whether in silence or in laughter, could become salve.

Image courtesy of Pardeep Singh Photography

We entered the living room of Paneet Singh’s creation with our own historicity of friendship. Our relation prior to experiencing the piece was part and parcel of our individual experiences. So often our interactions with media are considered personalized—crafted by our own family stories, life memories, geographic moves and personal shifts. However, Singh’s play allows us to articulate how we relate to each other and becomes a space from which we interact with the piece. And in this sense, we were forced into a liminal audience space, an in-between where we watched the play while watching each other. Someone else entangled in the intimacy of deep friendship might relate to our mutual vulnerabilities: we have participated in each others’ personal and inherited histories, families, and lives. The play itself evoked different affectual dimensions for each of us that we already had access to through our friendship. It affected us both differently, but simultaneously, and we understand those webbings as connective tissue, our relationality itself alive, conversant, and intertwined with the production.

Singh’s play was able to call out the webbings of collective audience-hood because he weaved his characters together across conceptions of home, trauma, and sacrifice. The phone, for example, was also a character, an important and connective symbol to homeland. There is a striking moment where Andy asks what was happening at the Sri Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar. Rani, accustomed to the tense phone calls her father makes to his brother in India, dismisses the tension: things are always happening, but everything is fine. She is, in some sense, desensitized to these small urgencies, or perhaps even tired of them and how they make their way into her Canadian life. Andy, however, is not desensitized, even to the violence of another community on another continent. A survivor of the Vietnam War, Andy is affected by the call and chooses to return home rather than continuing to hang out at Rani’s. The underlying message is that the effects of PTSD are so clear that Andy can trace the threads of violence before they are even palpable. We think of trauma as disorder(ing) and something we must rise out of, but Andy’s trauma is positioned as a second sense: his translatory knowledge that something is coming and his increasingly-frequent visits in spite of Rani’s father’s incredible violence towards his family. The deeply uncomfortable moments of Rani’s father’s wielding his financial power and landlordship over Andy and his family are still painful in spite of understanding how trauma itself is part of what has created uneasy connections to land and ownership.

…he weaved his characters together across conceptions of home, trauma, and sacrifice.

This complicated relation across diasporic history continues through Andy and Rani’s friendship and its evolution. As Rani experiences an emotional and intellectual struggle to find her own footing within the identity of a young diasporic Sikh woman, her narrative runs against her father’s reminders of the sacrifices that their family has made to provide safety. This dynamic interacts with Andy’s memory of his own family’s move to Canada. Singh holds these complexities together and allows each character the dignity of their own emotions and reactions towards one another and global iterations of violence. Perhaps it was here we were offered the ability to not only connect with the play, but to connect with one another—we could relay our own scholarly, personal, and emotional experiences across the room.

There are limitations to Singh’s representations of these characters, especially in conversations of nationalism and revolutionary politics. As scholars invested in anti-colonial critique informed by racial violence and settler complicity, we question how young women of colour, represented by Rani, are used for exploring questions about national identity. Our questions and conversations emerge from the recognition that the quest for nationhood is not necessarily for women. The climactic moment emerges through Rani’s tension with her father, Chattar, over attending the protests against Operation Bluestar. That is, Rani’s fight for her voice to be heard, her singular motivation in the narrative, is mobilized through the dimensions of nationalism; the fight for a young woman’s freedom is a common global narrative, and one that is deeply popular in North American diasporic, racialized contexts. This fight is co-opted by Singh, in an alignment that masks political calls for Sikh sovereignty within the rubric of woman of colour identity and injury that is more familiar and legible (and therefore, predisposed to higher sympathies to a wider Canadian audience than Sikh self-determination might be). Thus, Rani’s father becomes the antagonist because of his refusal to let her attend the rally, which itself becomes the dominant symbol for her freedom. Rani’s mother, Niranjan, becomes the sympathizer to Rani’s plight. And Andy, Rani’s best friend, becomes scale for injury, where his trauma as a refugee of the Vietnam War becomes collapsed with the trauma of Sikhs in 1984. We ask instead, can there be motivation and freedom for Rani, for young women of colour, extending beyond the politics of the national? To draw from critical feminist scholar Gloria E. Anzaldúa, “To survive the Borderlands / you must live sin fronteras / be a crossroads.”[1] Can we see Rani’s radicalism, her fight for autonomy, and her self-actualization outside of borders? What is lost when, again, women’s bodies become the battleground upon which the nation-state is staked and un-staked?

These are the kinds of conversations that need to be addressed as writers and thinkers of colour, as women and non-binary people. While we can and should call for equity in representation, we must also go deeper in our analyses to the questions of how the representation functions, to who is being injured and for what purpose? It cannot be that a young Punjabi-Canadian woman’s search for belonging is singularly mobilized for nationalist and anti-nationalist sympathies, nor that we uphold representation without critique and concern of this. To us, this is not de-colonial work.

While we can and should call for equity in representation, we must also go deeper in our analyses to the questions of how the representation functions, to who is being injured and for what purpose?

Vancouver overflows with racial politics, intimate tensions, and diasporic histories. We hope that Singh’s work allows us to pause, reflect, respond, and call for increased nuance, more entwined tracings and amplified webbings. We, for two, are grateful and excited by the opportunity to watch again, to watch each other, and for the people of this city to watch each other, too.

Image courtesy of Pardeep Singh Photography

[1] https://www.powerpoetry.org/content/live-borderlands

Review by Kiran Sunar and Kristi Carey. Kristi Carey holds an MA from the Social Justice Institute at the University of British Columbia. Kiran K. Sunar is a PhD student at UBC’s Department of Asian Studies. We are both grateful to exist on the traditional, ancestral, unceded, and occupied territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. A Vancouver Guldasta, written and directed by Paneet Singh, is currently playing at The Cultch until October 21st. Learn more here.