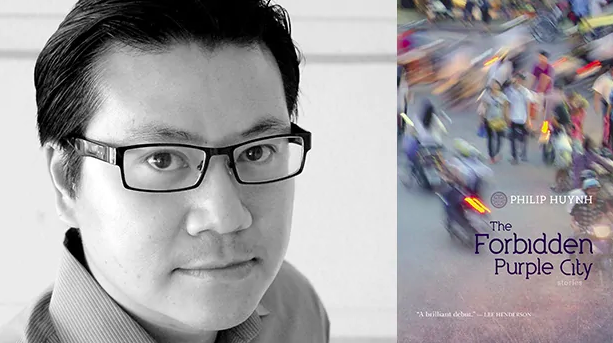

In 2016, Philip Huynh was the co-winner of the Emerging Writers Award. Philip Huynh’s stories have been widely published in literary journals and in the Journey Prize Anthology. As the son of immigrants, Huynh’s stories revolve around the Vietnamese diaspora and the book’s collection of stories feature a diverse array of themes and characters. Goose Lane Editions picked up the book shortly after the announcement of the award, and developed the manuscript into The Forbidden Purple City. Ricepaper interviewed Philip ahead of his book launch in Canada.

Your book speaks to the Vietnamese diaspora. Even the title is taken from the name of the walled palace of Vietnam’s Nguyen dynasty. How did you trace the experiences, the insight, and the memories of your characters back to your own roots to the diaspora growing up in Canada?

Your book speaks to the Vietnamese diaspora. Even the title is taken from the name of the walled palace of Vietnam’s Nguyen dynasty. How did you trace the experiences, the insight, and the memories of your characters back to your own roots to the diaspora growing up in Canada?

I share the roots of my characters’ experiences in my own life, and in the lives of those I grew up with. My family fled the war in Vietnam relatively early (escaping in the 1960s), and I was born in Vancouver just a few days before the Fall of Saigon in April 1975. People assumed that I was an immigrant too, because a Canadian-born Vietnamese was almost unheard of back then.

I grew up with immigrants, but I am fundamentally an outsider to them by being born here. There will always be things about their pasts that they will never share with me. I believe that this distance is useful from a creative point of view – it feeds my curiosity, forces my imagination to bridge the chasm between my life and those of whom I call my family.

And so my collection is indeed about the lives of the Vietnamese diaspora after the war, many of whom are coping with memories that occupy the strange terrain between trauma and nostalgia. The stories explore how the past haunts and even animates the characters’ present lives. Despite this focus, the characters are (hopefully) diverse and the settings are far-flung, from Vancouver and Winnipeg, to New York, to South Korea, to Vietnam. I write about the Vietnamese because that’s obviously my background, the prism through which I see the world. However, through this perspective, I do hope to touch upon matters of more universal interest – such as love, jealousy, and the ambition to make one’s way through often difficult and unfamiliar terrain. I found the short story collection to be a very effective form to explore a chorus of perspectives, allowing formal experimentation in voice and narrative structure to reflect the shape-shifting lives of these immigrants.

I liken reading your book to wandering through a dated map of Vancouver, Winnipeg, Hoi An, tracing their landscapes through each story. Do you compose each piece purely from memory, or did you need to go back and research parts or areas where you were unsure? In other words, how do you go about “fictionalizing” what is already familiar to you?

All of the stories are fictional (of course!), but some of the stories required more research. I’ve been to all the locales in my collection, but while I have lived in Vancouver, Winnipeg, and New York and know these cities quite well, I have only visited Hoi An, Hue, Ho Chi Minh City, and Jeju Island. This perhaps explains why the stories in Asian locales are told from an outsider’s perspective.

“Toad Poem”, for example, takes place in Hoi An but from the perspective of an elderly Vietnamese man who left the city in his youth for Canada. He is now back decades later and sees modern Hoi An more or less as any other tourist.

“The Forbidden Purple City” is also told from the perspective of a Vietnamese man who left Hue for Vancouver decades earlier. The Hue in the story is partly a city in this man’s distant memory, partly a complete fabrication of his imagination, and partly pieced together from what he can find through internet searches. Though the man is Vietnamese born and bred, he shares my outsider’s gaze upon his homeland.

Finally, “The Abalone Diver” is an immigrants’ tale – this time the immigrant is from rural Vietnam now living on an orange farm in Jeju Island, Korea. Again, we have a protagonist who is an outsider.

All of these stories took quite a bit of research (not only visiting the locales but reading up on various topics, such as abalone diving, the history of the Hue palaces, the art of historical restoration, etc.). But the point of the research was not simply to create an immersive read, but also to make vivid the strangeness of places that were once familiar to the characters. A number of them are struck by a sort of vertigo when they return to a foreign place they once called home. There is an abyss between what they see versus what they had in mind, and it is sometimes difficult to tell if it is their warped memories or a changed reality that is to blame.

But even the stories that took place in Vancouver or Winnipeg – cities that I have lived in for many years – took quite a bit of research. For “Mayfly”, which takes place in Vancouver, I had to do some extensive research on grow-ops and grow-rips. The Vancouver scenes in “The Forbidden Purple City” (such as the Tet concert) required almost as much research as the scenes that took place in Hue. Although I wrote “The Tale of Jude” without too much research initially, I remember my editor at Prairie Fire taking me to task on how the characters couldn’t really get around Winnipeg because the streets weren’t actually laid out the way I described them. So much for trying to work from memory!

I compared your published book and the stories from the manuscript that eventually won the 2015 Emerging Writers Award Toad Poem. I’m pleasantly impressed that, for the most part, the stories and the text resemble that original manuscript, which is not always the case when a publisher accepts and then heavily edits it to the author’s dismay. However, there is one story, “Mayfly” that is new to the collection from the one you had submitted. What is the significance of this story? Is it entirely new or one that you chose from an earlier piece of writing? Could you tell us more about this piece?

Firstly, I have to thank my superb editor Bethany Gibson at Goose Lane Editions for her eagle-eyed and probing work on the book. You are right – the stories have remained essentially the same, but I wouldn’t call the book lightly edited. It seemed like she interrogated every sentence and we worked on the edits for months. There are many changes between the version that I submitted to the ACWW and the final book, though most of them are at a level that wouldn’t attract much notice. Just one example is in the beginning of “The Abalone Diver”, when the protagonist Thuy bloodied herself on thorns while picking mandarin oranges. Bethany called me out on the fact that mandarin oranges didn’t have thorns! I still needed the blood to appear in the opening, and so I revised it so that Thuy pricked herself with a pair shears. There are a hundred of these critical micro-moments that I had to change due to Bethany’s acuity.

As for “Mayfly” – it is a story that I wrote after I won the Emerging Writers Award. It’s about a red-headed kid who just happens to be going through his adolescence in East Vancouver in the early 1990s. His parents have separated and he is living with his dad in his grandfather’s house. He is bullied at school, doesn’t feel like he belongs anywhere, but wants so desperately to belong somewhere. And so he falls into the rabbit hole of a Vietnamese gang led by an elder called Brother No. 1. The gang is engaged in a hierarchy of rackets – from petty thefts, to home break-ins, to grow-ops, and then (at the apex of the pyramid) grow-rips.

This might sound odd, but what I thought the collection was missing was a story written in the second person. I have ones written in the first and third persons – even one that uses “we” – but nothing that starts with “You”. As a kid I loved Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City, which uses the second person to great effect. But it is the rare story that calls for it. It’s an accusatory way to address a protagonist, and one that heightens the alienation between the protagonist and the world he inhabits. Which is why I thought it suitable for this particular story.

You’ve commented that you’re like a “yo-yo with Vancouver,” having lived in different parts of Canada and the United States. You’ve also shared your views of how the city has changed over the years, amazed at how much it changes upon each return. Now that you have settled here in Vancouver, how has the shifting landscape and demographics shaped your current writing?

When I “yo-yoed” between Vancouver and other cities, I certainly noticed how much it changed every time I came back. Although I have stayed put in the Metro Vancouver for the past decade, the changes are still jarring even though I have my nose pressed up to the city every day. Vancouver’s demographics were much more limited when I was growing up, and the city has become a conduit for so many more cultures now, both from Asia and elsewhere.

Today’s Vancouver is doubtless an exciting place to write about, but with a few exceptions, I haven’t yet focused much on the present day. The Vancouver in most of my writing goes as far as the mid-1990s. Maybe it’s simply that raw experience takes a long time to ferment into creative material. I will say, though, that when I grew up in Vancouver in the 1970s and 1980s, I felt the isolation of being a Vietnamese person quite poignantly, and I think these feelings have informed some of my writing. I don’t think I would feel the same way growing up in Vancouver now as a Vietnamese, where the pho restaurants seem to outnumber the Starbucks. But then again, all this rapid development and hyper-interconnectedness seems to breed its own species of alienation and grist for introspection.

You did not graduate in the MFA Creative Writing program. Rather, you found your own way as a writer, publishing your short stories in literary journals and even had one of your stories longlisted in the Journey Prize anthology in 2013. You did this all the while working full-time as a lawyer and raising a young family. How did you create the mental space clear of distractions to do the work that allowed you to be successful?

Although I studied English literature at UBC, I went to law school instead of pursuing an MFA. I think in some ways the law has been a great training ground for my life as a writer. It has allowed me to live in different places (New York, Toronto, and Vancouver), exposed me to different worlds, gave me a lot of practice sifting truth from falsehoods, and perhaps above all else, has drilled into me this determination to get whatever needs to be done no matter what my mood might be.

I used to work at a large law firm in New York City, and the joke was that we would all work 9 to 5 (9 am to 5 am). The firm had its very own cafeteria so that the lawyers didn’t have to leave the building when they had their dinner every night, to maximize efficiencies. We young lawyers devised creative ways to maintain a social life despite having to clock huge billable hours. Sometimes we’d leave the office at 6 pm, go to a show on Broadway, then go back to the office after the show was over. That sort of thing.

I work in the Vancouver area now, and the work/life balance is much more humane. Because I’m married with kids, I don’t quite have the social life that I used to, so after my kids are in bed, I have the opportunity to get some writing done. I think much can be accomplished if you are somehow able to carve out even half an hour a day.

As to ensuring the right mental space? Let me offer you a quote by Joyce Carol Oates that sums it up for me:

“I have forced myself to begin writing when I’ve been utterly exhausted, when I’ve felt my soul as thin as a playing card . . . and somehow the activity of writing changes everything.”

Do you have any words of wisdom for those who may not have the luxury of entering a professional writing program, but still aspire to write and publishing a novel one day?

Since I have not published a novel myself, you’ll have to take my words of wisdom with a grain of salt! But here it goes:

Remember that there is a great tradition of writers who kept day jobs and never had an MFA. Chekov was a doctor. Kafka worked in insurance. Faulkner worked the night shift at a power plant. The list goes on. And I’m sure that for the most part, getting an MFA doesn’t absolve you from having to juggle job, family, and art.

So try to write every day, even if it is just for half an hour.

I imagine that one of the great benefits of a professional program is the support network of writing peers, which is something that I don’t have as much. I’ve found my MFA substitute in literary journals like Ricepaper, The New Quarterly, Event and others. It’s by subscribing to literary journals that I was able to read what my peers were doing, even though I never met them personally. And it was by submitting to these journals that I was able to become part of the literary conversation and to build up a track record leading up to my first book deal. I consider the writers I’ve published alongside in these journals to be my comrades-in-arms. One of them blurbed my book even though I have never met her personally!

Even getting rejected by a journal is a valuable experience, because you learn what’s working and what’s not with your writing. It’s important for writers to get feedback on their work, to be able to somehow measure their progress, and I think there are many outlets to do so outside of the professional MFA. There are more informal writers’ groups, temporary retreats, online courses, you name it. For me though, my lab and proving ground has been the journals.

Has your background as Asian ever become a barrier to your writing? At the same time, has your Asian background/identity ever given you opportunities that you might not otherwise have had as a writer?

I’m relatively new to the publishing world, so at this point I have less to say about whatever barriers there may be in publishing. The barriers that I have noticed are perhaps inherent in any immigrant culture, and stand in the way of getting the writing done in the first place. For the immigrant, fanciful dreams of art take a back seat to the daily business of survival. And there is the age old question that parents pose to their children – “Did I risk my life to cross an ocean to spend my days breaking my back, so that you could starve and write poems?” Even though my parents never asked me that question, perhaps I asked it of myself. After all, I did become a lawyer, a very filial choice for an occupation. I only started writing in earnest well after I established myself in the law, when I no longer felt that I needed to choose between art and food.

Otherwise, when it comes to writing, being Asian has been a gift. Things that cause suffering in day to day life – being an outsider; having a double perspective; never feeling truly comfortable in one’s skin – all these things are succor for one’s writing.

And now, having been able to get some of the writing done, I find so far that I have publishing opportunities as an Asian that I would not otherwise have. Winning the ACWW Emerging Writers Award is just one example. There is also a serious audience for Asian Canadian literature, and I count the readers and contributors to Ricepaper among them. While perhaps not large, the audience is devoted, and they will find you. The trick is to get the writing done.

Did you ever have doubt that your Asian characters or themes would not be accepted by audiences/editors/publishers?

I don’t worry about that. I wouldn’t be writing short stories in the first place if my ambition was to be embraced by a vast audience!

But seriously, I believe in writing to one’s pre-occupations, whatever they may be. I also think that readers can see through a writer’s transparent attempt to write to certain themes simply to chase a market.

I do believe though, that if the writing is sincere and hard-fought for, it will find an audience no matter what colour the characters are or how weird the food is. Beyond the ethnic veneer of the characters in my book is, I hope, a depiction of urgent human concerns with universal resonance.

I remember picking up your manuscript and discussing it with Jim Wong-Chu. We were excited about the confidence and tone of writing, how the entanglement of stories and characters speak to our complicated hybridity of being both Asian and Canadian. What’s your advice to a writer who wants to write and but is unsure about how to address uncertainties of his or her identity? What can they learn from you and your experiences?

My first piece of advice with writing is that there are no rules. Everyone has their own way that works for them to get the words on the page.

That said, pay heed to your own obsessions. I believe that, to a certain extent, the subject that you were meant to write about chooses you. So if you want to write about a space station in Mars, do that. If you want to write about your ancestors, do that.

I am writing at a time when the pioneers of Asian Canadian writing have already blazed a path. Call me a second generation, maybe even third generation Asian Canadian writer. There are benefits but also challenges with this. I feel that writers of my generation do not have the same burden of bearing witness or being the voice of a people the way that the earlier generations may have felt. This can be quite liberating. This means that you can write about anything you want. This means that as a writer, you might choose to ignore being Asian Canadian. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course.

For those like me who have a hard time ignoring their Asian Canadian identity, I have this advice from Confucius: respect your ancestors. It would be disrespectful to write a pale imitation of what your ancestors wrote, and to avoid doing so, you first must know the precedents, what stakes have already been planted. Be familiar with their words, be it those of Joy Kogawa, Madeleine Thien, Kim Thuy, or Michael Ondaatje. Give the words of your predecessors the proper respect, know what they’ve done, use their wisdom, then forge your own path.

Join author Philip Hyunh at Massy Books on March 28 for the Vancouver launch of The Forbidden Purple City from 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM.