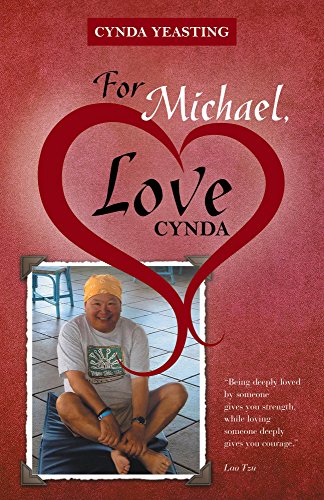

Cynda Yeasting

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada to a Pioneer Chinese family, Cynda Yeasting is the eldest of a family of five. She is a second generation Vancouverite. Although she is adventurous and has been fortunate enough to travel to some wonderful places in the world, Vancouver is where her heart is most content. She has strived to live a life without regrets and to always remain true to herself. Loving and being loved by Michael is one of the greatest joys in her life. LiterASIAN’s Sophie Munk interviews Cynda as part of a series of profiles of this year’s lineup of authors.

Your memoir, For Michael, Love Cynda, tells your love story, detailing the highs and lows that come with loving a partner with terminal cancer. How did you decide to write this book?

I have always been someone that likes to record events. Ideally in writing, but also in photographs. Memories fade over time and it was really important to me to write down my feelings and experiences as they were happening. I knew that short of a miracle, Michael would eventually die and I never wanted to forget any of our time together. The good and the bad. I like to journal and had a diary as a young girl so it was natural for me to write down how I was feeling and what we were dealing with on a regular basis. His family wanted to be kept informed and sometimes it was easier to write, than to speak on the phone. For the longest time everything I wrote was for me, so I would have this, after he was gone. He told me more than once that he never wanted to be forgotten. We wrote lengthy emails to each other, even though within weeks of meeting, we talked daily or saw each other. Those emails were love letters and they are a gift.

I took a workshop with the writer J.J. Lee and J.J. said words to the effect of, it is not that you want to write the memoir, but that you are compelled to. I felt the intense need to write out everything that happened, all the good and the bad. I was careful to not share anything in the book that might upset anyone in Michael’s family. But I was also mindful that I did not want a glossed over version of life as a caregiver and loving a terminally ill person. If I was going to share my story, I wanted to share the reality of how hard it was. I wanted my book to help someone who was dealing with loss, anticipatory grief or was a caregiver or terminally ill.

In the Asian culture, we are very superstitious. We do not wish to talk about death. And not just in the Chinese culture, but also Western society. Up until I would say about 10 years ago, no one wanted to talk about grief. Grief is loss. Not just to death, but loss of life as one knew it. With the pandemic, we are now talking about grief. Loss of the life we were used to having. Grief from death is also loss of the life you were used to having. I had a life with Michael and we were part of each others daily lives for about 19 months. Then he was gone. I moved back home to my two sons and I no longer lived with Michael, I went back to my life before Michael, but I was, and have never been the same again.

Writing the book was one thing, but publishing it was another. To share my story, I did so for others dealing with loving someone with a terminal illness. The stress of being a caregiver and then the grief afterwards. My book did not end with Michael’s death, but continued with my life afterwards. It was very important to me that it end that way. Our story was unusual in that he was terminally ill when I met him. I took a chance on him and on love. I do not know how to explain it, but I was so certain that if I did not meet with him, I would regret it for the rest of my life. In our first phone call, Michael told me he had terminal cancer. He gave me a chance to get out. When I met Michael, I had everything to lose by getting involved as I was very physically fit, happy, owned my own home, and had a good job.

I did my research on the internet and found two stories like ours. I did not think someone else had the same experience as I. Definitely rare.

I truly believe that if people talked more about death and grief that we would be better at coping with both. When someone dies, everyone is great about being there, lending a hand, being supportive and over time that fades into the background. It’s human nature. But the person who has had the loss, still lives with the loss, every day for the rest of their lives. The loss becomes part of who they have now become.

I am proud that my book has been read by a few cancer survivors. It was also read by a caregiver whose husband was dying.

What was the writing process like? What helped and/or hindered you?

It took me about 7 years to finish writing the book. It took so long as I was also working full-time, but also because it was so incredibly emotional. Everytime I wrote, it brought me back to that particular time. The memories were vivid and I was reliving those times all over again. When I was with Michael, it was often not a good time to be emotional or to cry. I had to put my feelings on a shelf and wait for when I would have time to deal with them. Same with writing the book. I would get overwhelmed by the emotions and have to take a step back and put it on the shelf for a while.

I have not taken any writing courses. I have always enjoyed writing since I was young. I got excited when I had an essay to write in school. In my day job I draft correspondence on a regular basis. I wrote my book the way I would speak when I am sharing a story. I have been told that my book is an easy read of a tough story and I am grateful to be told this. I believe it would have helped if I had help in how I structured my book. My story is chronological. I am not sure if there was a better way. I am happy with how it turned out, but guidance is always valuable.

What advice would you give to someone with a terminally ill loved one? What did you learn from this experience?

What advice would you give to someone with a terminally ill loved one? What did you learn from this experience?

Death should not be feared. It is not the end. I have had proof. It is “loss” that is so hard. Loss of the love you received from the person who dies. Loss of the life you had with that person. The dying can be so much worse for those in excruciating pain. When the medication dosage can no longer be increased and the patient is in agony. This was not the case with Michael, he was fortunate, but we heard another patient in the hospice and it was heartbreaking. The suffering that we allow humans to be subjected to, but would not hesitate to put an animal out of misery. I hope that assisted dying becomes a conversation that more people can have without feeling “bad”.

Do your best to talk to the terminally ill loved one normally. Get mad at them, talk to them, don’t tiptoe around them. Be real. They need that. I got mad at Michael and ripped a strip off of him. It was not easy to do that but I had to, because he needed to know how I felt. We didn’t have the luxury of hoping we could work it out over time. We didn’t have time. Be as normal as you can. Have fun. Laugh, cry and talk about death and dying. Not talking about it does not mean it doesn’t exist. It makes it harder on the dying person if their loved ones do not accept that they are going to die.

I moved into palliative care with Michael and when I checked him into hospice care, I moved in. I know that many family members spent significant time there, but most went home. I did not want him to wake up alone in the middle of the night. I would not want to, if it was me. Since 2015, we have Bill C-14 in Canada which has formally legalized assisted dying. I have not read it in its entirety, but my understanding is that it gives a terminally ill person choices. I have three sisters and a brother. One of my sisters said to me that I am true to myself. I followed my heart and am grateful I did. As much as the loss hurts, I experienced a great love, and for that I have no regrets.

***

Cynda Yeasting will be at LiterASIAN 2021 as part of a panel, “Independent Authors or Self-Published Authors? Stories that We Live to Write About” with Jackie Lau, Diana Ng, JF Garrard, & Diana Morita Cole May 8th, 12.00pm – 1.30pm (PST). Register here for your ticket.