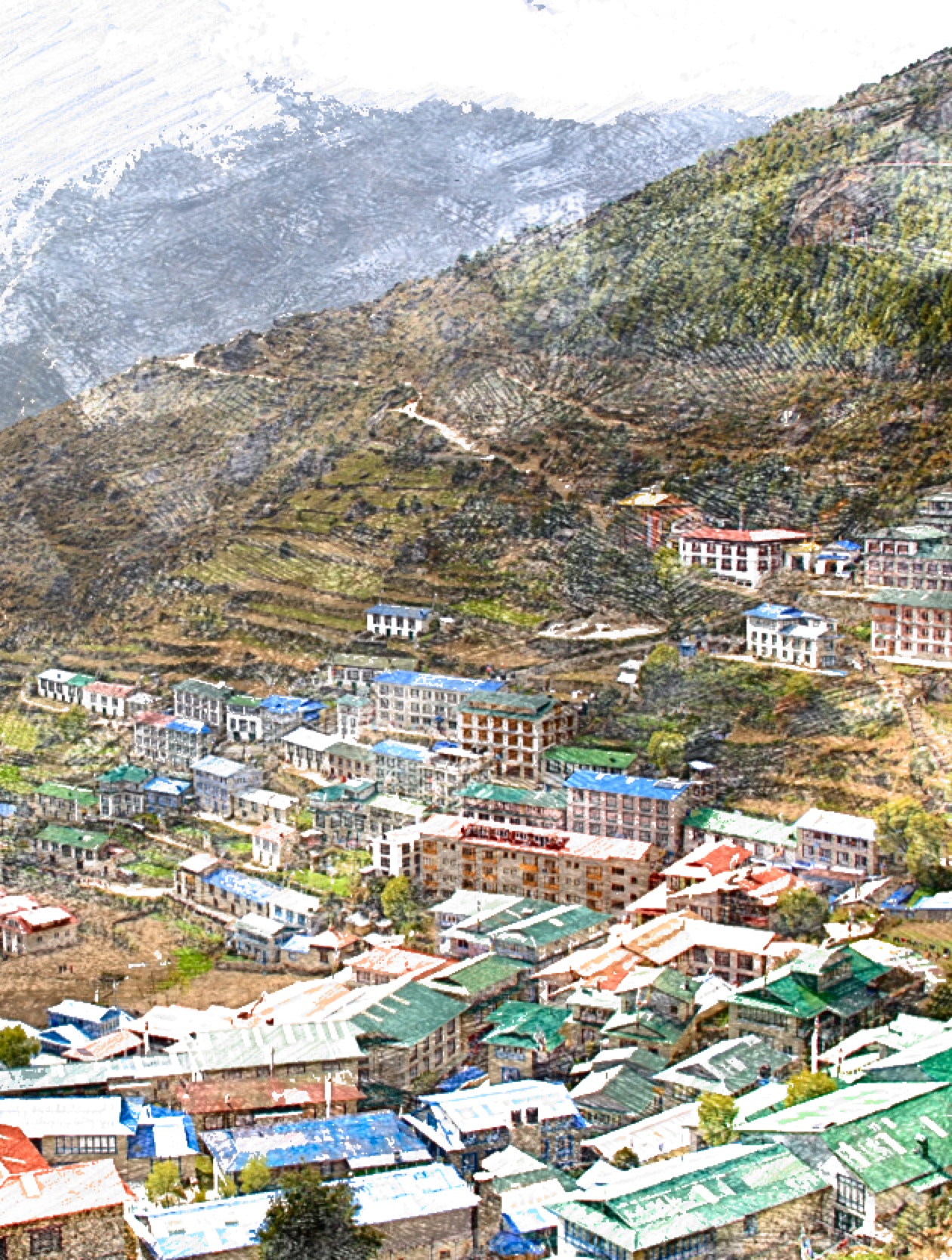

Illustration by Anderson Lee

The words were waiting to be needed. They gush out of me, and I’m left wondering if I believe in a god, or three million of them, after all. For so long, I had run from them, afraid of their hold on me. I had run until I had found myself, aged 19, lying on the floor of an apartment in Vancouver. I’m crying over a boy. My eyes are puffy, my lips are chapped, and my throat is hoarse. I am lonely in the way only a first heartbreak can make someone feel.

I plead: He bhagwan, shakti dinus. Oh, Lord, grant me strength.

*

My mother, her sisters, and my grandmother asked for strength all the time. The occasion didn’t matter. They said it during lazy afternoons spent at my grandparents’ house in Kathmandu when an afternoon downpour and the prospect of a wet, muddy rickshaw ride home was an inconvenience that required the assistance of the divine. They whispered it quietly at a family gathering when the arrival of estranged family members brought up generations of conflict. My grandmother said it loudly during a lull in the conversation, as if she needed something to ground herself, and only the gods could do that for her. Everyone needed bhagwan.

My father, attempting to lighten the mood, would ask if a traffic jam, a regular occurrence in the narrow, overcrowded streets of my hometown, really required one or more gods to intervene. “Do you really want to bother a god with that?” he’d say. He’d laugh, confident that his joke would land despite the frequent repetition. That was his strength.

It wasn’t ever reassuring to my mother. Sitting anxiously in the passenger seat of my parent’s car, she would rummage through her purse to find something that would provide momentary comfort in this unmanageable situation. She’d fish out a cough drop, or wrap herself

even more tightly in her paisley-patterned shawl. Perhaps that was Parvati acting at the moment to assure her that they would get to their destination soon enough.

The incantation wasn’t one I relied on. What could these gods do for me? I knew the expectations that came with being raised a woman by parents practicing conservative, Brahmin Hinduism. I didn’t ask Ganesh for strength as my mother told me, aged only 11, that my first period meant my body was changing, and that I should make sure boys didn’t look at me. I didn’t ask Krishna for help as she sat me down on the carpet in her bedroom three years later, her phone’s handset still warm from a long conversation with her cousin, whose son had dared to marry someone non-Nepali. “If you ever do that, I’ll never speak to you again,” she said, her eyes ablaze. Staring at the pink flowers on her bedsheets to avoid eye contact, I didn’t think there was a god anywhere who would douse that flame for me. I thought only about never becoming the match that lit it. In an instant, I became good at keeping secrets.

I didn’t ask any gods for guidance on the evening I left Kathmandu to go to university in Vancouver. We didn’t know it then, but I wouldn’t return to Nepal again. As she prayed with a fervor I had never seen before, I sat beside my mother in her puja room, a fragrant marigold garland around my neck, red tika on my forehead, and a knot of relief and sorrow in my stomach. My right hand’s fingertips were stained red from the red and orange abir and sindhur we’d used during the puja. They would remain that colour for a few days, traveling with me across the Pacific Ocean. I stared down at the murtis of gods and goddesses in front of me, daring them to appear and punish me. I was convinced this was my farewell to pujas.

And yet, the words found me, all those years later on my cold vinyl floor. After that first encounter, they would find me at other times. They scared me with their brazenness, the audacity to make an appearance uninvited. I kept pushing them away, but they knew I needed them.

*

For the women who raised me, being a woman was dukha. They lived in multigenerational homes with their in-laws, who treated them poorly and expected perfection from them. Their lives were weighed down by the pressure of being subservient daughters-in-law, generous wives, and strict mothers. They were instructed to give up or scale down careers, conduct countless religious ceremonies, and raise children who did the same. Despite this, they were pragmatic about their suffering. Long conversations recounting the hurt they had endured often ended with one of them saying, “estai ho.” This is just the way it is. “Ke garne?” What can we do? There were only two things they thought they could control: their children and their prayers.

With their requests to the gods, they were showing me where to turn for comfort. They taught me I would need strength. To their horror, I found enough of it to leave. That my mother threatened me as a teenager makes sense now. She was scared for me. She was scared of me. She may have asked for the gods’ help, but nothing turned up. Her threats were the only way she knew to reach me.

I have been estranged from these women for eight years. In this time, we have grieved deaths, illnesses, and natural disasters. Now, in a pandemic that has hit Nepal particularly hard, my aunt has died. Each time a tragedy has occurred, our sorrow has been a momentary closing in the chasm between us. There are short phone calls, during which tears flow freely, and silences are long and painful. The moment will pass, and the distance will return.

Grieving in estrangement relies on imagined interactions. There are no communal rituals or conversations with the people who knew my aunt best. I fill the void of lost time and missed opportunities with daydreams. I’m sure it’s not always accurate, but it’s all I have. Using all those afternoons in my grandparents’ house as a blueprint, I dream up what my aunt and I would say to one another if we sat in a room together. A few minutes into our conversation, her booming laugh would bring her sisters and mother into the room, wanting to join in on the fun. We would talk about the most fashionable kurthas of the day and trade lipsticks, seeing which shades look best on each of us. A funny family anecdote would get retold, each of us shouting over the others to tell our versions. The stories are long now, new details have been added at each retelling. Inevitably, the conversation would transition to family dynamics. Old wounds and disappointments would resurface. Someone in the room would bring up dukha, and I’d ask where my aunt sought solace. She’d say she found it in puja, in bhagwan, in doing what she had to do. Estai ho.

*

Today, there isn’t an altar or a murti near me in my home. I close my eyes. Before the tears come I ask for strength. For me, and for the women I love and resent. I’m closer to them than I had thought.

Sambriddhi Nepal (she/her) is a Nepali settler living on unceded Coast Salish Territories in Vancouver BC. She works at a human rights organization by day and writes creative non-fiction and children’s books when everyone in her household has gone to bed.

2 comments

Thank you, Sambriddhi. Your words are beautiful. Envisioning your stained hands on the plane ride had me breathe a big breath. Thank you.

Wow. You’ve put into words something I’ve never quite known how to express. Thank you.