By Margaret Inoue

In 2010, the Japanese Canadian National Museum featured a photo exhibit of Japanese internment camps, which presented the contradictory but unique perspectives of American photographer Ansel Adams and Canadian photographer Leonard Frank.

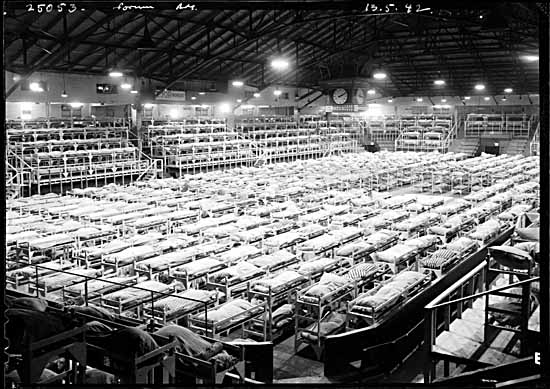

Building K, Men's Dormitory (formerly Forum), Hastings Park, Vancouver, BC, 1942; Photo by Leonard Frank, VPL Accession Number: 14918

How do we learn about our past? How do we tell our historical stories? These questions are not as easy as they sound, since history is never just about dates and names. The stories that shape our communities – and the ways in which we understand them – are inextricably linked to how they are represented and interpreted.

In Canada, it is difficult to talk about Japanese Canadian history without talking about the removal and confinement of people during World War II (WWII). How this story was generally understood back in 1941 and how it is understood now are very different. In 1941, despite military and police intelligence providing evidence to the contrary, newspapers, lobbyists and politicians depicted all people of Japanese descent as untrustworthy and dangerous. Or, if not dangerous themselves, then in danger of being the target of violence or race riots.

Fortunately, contemporary history texts are now exposing the racism underlying such political actions, and thanks largely to the redress movement in the 1980s, the forced confinement and work camps are recognized as an injustice rather than a requirement of national security. On September 22, 1988, the federal government of Canada acknowledged its role in this, officially apologizing for the actions and providing some compensation to the victims.

Frank’s photos record the Canadian experience, while Adams’ photos record the American experience. By placing two national experiences side by side, the exhibit and program presented audiences with a unique perspective.

In the United States, Japanese Americans faced a similar experience; those living on the coast were rounded up and confined in camps purportedly under the suspicion of being a threat to national security. However, unlike those living in Canada, Japanese Americans had more time to prepare for their relocation. While they were confined in smaller camps fenced with barbed wire, they didn’t have to pay the bill for their own confinement. When the war was over, Japanese Americans were allowed to return to their homes and possessions. Their experience in the American camps themselves, though, was varied and was entirely dependent on the personalities of the people running the camp. In the 1960s and 1970s, the community pushed for acknowledgement of the injustice as they did in Canada a decade later.

For many, there is still much to learn about the Nikkei experience in WWII. Greg Robinson writes in his book The Tragedy of Democracy, “there remain serious conflicts over how to interpret [the confinement camps’] legacy,” noting that people continue to question whether the removal and confinement were caused by “wartime hysteria” or generalized racism, and what the impact of these events were. Robinson also notes that there are even some who still rationalize or justify the removal of the Japanese Americans. Beth Carter, director and curator of the Japanese Canadian National Museum (JCNM) at Nikkei Place in Burnaby, BC, reflects that “we still have to fight hard to make sure that the Japanese Canadian story gets better known.” She noted that many schoolchildren are taught about the confinement of Japanese Canadians, but do not understand the hardship or experience because of the disconnect from their own experience. Like Robinson, she has also encountered some who still rationalize the actions of the government in removing and confining Japanese Canadians.

Although the movements for redress in both countries were successful in achieving official apologies, the story needs to be told in a manner that connects with those not affected by the incidents directly. One of the places that actively engages in telling these stories is the JCNM; at Nikkei Place at Burnaby, BC, where part of the mandate is to tell the story of Nikkei in Canada including the WWII period, through its learning centre and periodical museum exhibits.

From January 16 to March 13, 2010, the JCNM presented works of two photographers, Leonard Frank and Ansel Adams, both of whom depicted the confinement camps and the experience of Nikkei in North America during WWII. Frank’s photos record the Canadian experience, while Adams’ photos record the American experience. By placing two national experiences side by side, the exhibit and program presented audiences with a unique perspective, given that little work has been done comparing such experiences in the countries of the Americas and Australasia during WWII. These photos had previously been on display as part of an exhibit at the Presentation House Gallery in 2003, where the Frank and Adams photos were shown alongside those by Dorothea Lang. The JCNM version of the exhibit was conceived as a travelling exhibit, and will hopefully be mounted at galleries across the country in the near future. In addition to the photos, the exhibit included two videos: a Leonard Frank documentary and Pilgrimage, a documentary about the American experience with the confinement camp called Manzanar. The museum also held a series of related public events including talks by Bill Jeffries, director/curator at the SFU Gallery and Greg Robinson, history professor at l’Université du Québec à Montréal.