As a translator of Chinese comics and folk rock who lives in Vancouver, BC, Nick Stember is an expert of Chinese comics, or manhua. In addition to building the world’s first English language encyclopedia of Chinese comics and animation, the Encyclopædia Manhuannica 漫畫百科, Nick is a consultant for a variety of ventures, including Storycom and Clarkesworld Magazine’s Chinese Science Fiction Translation Project and the Grayhawk Agency and the Ministry of Culture (ROC)’s Books from Taiwan Vol. III: Comics. Ricepaper took the opporunity to interview the Vancouver native Nick Stember about the world of manhua and its significance in the history and future of storytelling in Asia.

Most people probably aren’t aware that comics and cartoons (known in Mandarin as manhua) have existed as form of popular entertainment in Taiwan and China for at least a century, in comparison to Japanese manga. Why are Chinese comics almost completely unknown to your everyday English-speaking comics fan?

It’s impossible to know for sure, of course, but (since I study the subject) I have a couple of theories:

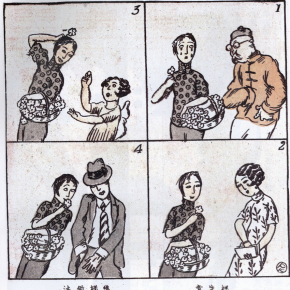

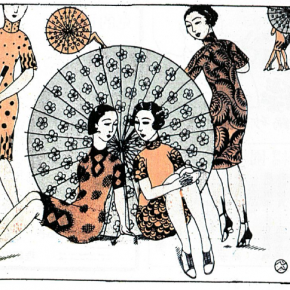

First, Japanese manga has been wildly popular in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and other Sinophone communities since at least the 1970s, if not earlier. The earliest influences on Chinese comics, starting in the decades following the Opium Wars of mid-19th century though, were actually illustrated broadsheets, political cartoons and newspaper strips—the later becoming really influential during the 1920s and 30s. These early cartoons, which came to be known as manhua in the mid-1920s (thanks to the work of an artist named Feng Zikai who had studied abroad in Japan), were largely influenced by American and European artists, with cartoonists like Zhang Guangyu taking inspiration from Vanity Fair cover artist Miguel Covarrubias, and Ye Qianyu modeling his cartoon strip Mr. Wang on George McManus’ Bringing Up Father. Because the iconic Japanese manga style hadn’t been developed yet (owing so much to the post-war cartoons of Osamu Tezuka) it’s harder to see the influences of Japanese artists on Chinese ones during this time period, although there almost certainly was a great deal of cross-fertilization going on. But even with all this, the drawback is that looking at these cartoons now, they don’t usually strike the viewer as being typically Chinese. In fact, the artists were working hard to make their work look like anything but.

First, Japanese manga has been wildly popular in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and other Sinophone communities since at least the 1970s, if not earlier. The earliest influences on Chinese comics, starting in the decades following the Opium Wars of mid-19th century though, were actually illustrated broadsheets, political cartoons and newspaper strips—the later becoming really influential during the 1920s and 30s. These early cartoons, which came to be known as manhua in the mid-1920s (thanks to the work of an artist named Feng Zikai who had studied abroad in Japan), were largely influenced by American and European artists, with cartoonists like Zhang Guangyu taking inspiration from Vanity Fair cover artist Miguel Covarrubias, and Ye Qianyu modeling his cartoon strip Mr. Wang on George McManus’ Bringing Up Father. Because the iconic Japanese manga style hadn’t been developed yet (owing so much to the post-war cartoons of Osamu Tezuka) it’s harder to see the influences of Japanese artists on Chinese ones during this time period, although there almost certainly was a great deal of cross-fertilization going on. But even with all this, the drawback is that looking at these cartoons now, they don’t usually strike the viewer as being typically Chinese. In fact, the artists were working hard to make their work look like anything but.

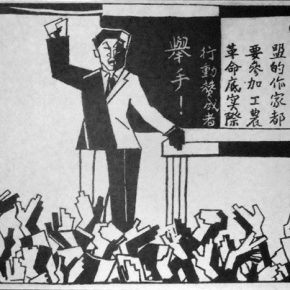

Following the outbreak of WWII in China in 1937 with the invasion of Shanghai, many Chinese cartoonists and artists devoted themselves to making anti-Japanese propaganda. This didn’t really end in 1945, because only a couple of months later there was the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek, and the Communists, at that point led by Mao Zedong. When things finally reached a détente in 1949, with the Communists on the mainland and the Nationalists holed up in Taiwan, there wasn’t much of a let up on the politicization of comics, so the big influences during the 1950s are anti-American Soviet political cartoons in the PRC, and anti-Soviet American political cartoons in Hong Kong and Taiwan. And of course illustrated literature for children and the masses, which led to a big boom in lianhuanhua, or ‘linked-picture books.’

These had been around since the turn of the century as mostly retellings of classical stories and operas, but post-1949 you increasingly see them co-opted for political purposes, taking cues from the socialist realist movement that’s much better known for its posters and statues. While these are very different from the kind of comics being produced in North America (and Japan) at the time, the political factor means that nowadays they’re mostly looked at by scholars of political science rather that art historians or historians of visual culture. It’s unfortunate, but it’s something that’s doubtless going to change as more people start doing research into the cartoons produced during this time period.

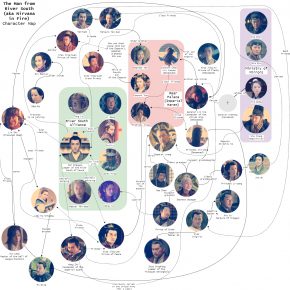

Moving into the more contemporary period, as with the rest of Asia, Japanese comics started having a big influence on cartoonists in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and eventually in the PRC too. So one criticism I hear a lot when I show people Chinese language comics is that they look too Japanese—people want to see something different, maybe more along the lines of European comics, which have their own tradition thanks to artists like Hergé in Belgium and Moebius in France. Fortunately, thanks to crazily prolific cartoonists like Ma Wing-shing and Wong Yuk-long, Hong Kong has (or at least had) a very strong tradition of martial arts, or wuxia comics, which have attracted a niche audience of comic fans here in North America. And there are a handful of artists producing underground comics, although the limited market for their work means that for most of them it’s a hobby, not a career. One exception whose work has been finally getting its due is the Chinese-Malaysian cartoonist Sonny Liew, whose Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye became the first graphic novel to win the Singapore Literature Prize for fiction in 2016. Sonny is a long-time comics creator who works in English and has much of his fan base in North America. At the same time his own background means that he is able to bring the Chinese diaspora experience in SE Asia into the mainstream in a really unique way.

So the short answer, I suppose, is that Chinese language comics, with a few exceptions, haven’t been able to build a brand for themselves in the way that Japanese manga has, or Korean webtoons are now starting to. A big part of this happens to be tied up in the politics and history of the region. But the important thing to remember is that we shouldn’t see this as a failure of Chinese comics. Really it’s a failure of audiences abroad to get outside of their comfort zones and challenge themselves to experience something new and different.

You’re working on the The Encyclopedia Manhuannica, which is the world’s first English language reference work on Chinese comics. Can you tell us more about this initiative?

The Encyclopedia Manhuannica grew out of my research at UBC while working on a Masters in Asian Studies. My supervisor, Chris Rea, had done research into Republican-era cartoonists as part of his larger project to explore the role humor played in the literature and visual culture of China during the 19th and first half of the 20th century. At the time, I was mulling the idea of doing a PhD thesis on the history of Chinese comics and cartoons in over the past 150 years. I’ve always been more of a ‘big-picture’ kind of guy, so the idea of writing this big long narrative and trying to trace the development of cartoons in China over time really appealed to me. The Encyclopedia Manhuannica represents my attempt to document the process of my research and also provide a resource to other scholars working in this field. In a somewhat tangential way, it’s also a response to the challenges of being a scholar in the 21st century.

The Encyclopedia Manhuannica grew out of my research at UBC while working on a Masters in Asian Studies. My supervisor, Chris Rea, had done research into Republican-era cartoonists as part of his larger project to explore the role humor played in the literature and visual culture of China during the 19th and first half of the 20th century. At the time, I was mulling the idea of doing a PhD thesis on the history of Chinese comics and cartoons in over the past 150 years. I’ve always been more of a ‘big-picture’ kind of guy, so the idea of writing this big long narrative and trying to trace the development of cartoons in China over time really appealed to me. The Encyclopedia Manhuannica represents my attempt to document the process of my research and also provide a resource to other scholars working in this field. In a somewhat tangential way, it’s also a response to the challenges of being a scholar in the 21st century.

I love the weird, random things that people get to study in academia, but my own experience of grad school has been a mix of deep connections with people who get what I’m doing and relative isolation from people who don’t. There is a sense among a lot graduate students I think, that you just need to keep your head down and do good work and everything will be fine. Research is valorized in a way that networking and service and teaching are not, and I think the extreme challenge of finding a tenure track position in a more desirable location (like Vancouver!) contributes to this. There’s a sense of fatalism among grad students that I’ve talked to (probably brought out by own pessimism) that says doing a PhD is this crazy, Quixotic thing that probably won’t turn into a real job at end of it. In a weird way, the attitude that academic research is pointless I think justifies or at least takes attention away from the genuine exploitation that is going on, of sessional instructors, adjuncts and grad students, and fuels some of the outrage (real or imagined) over how diminishing resources are being allocated. It also helps administration put pressure on tenure track faculty, who more and more are being set up to fail by being asked to balance heavy teaching loads with competing demands to publish their own research and train and manage grad students, while also somehow squeezing in time for more general service to university and staying current in their field. It’s a trend that encourages everyone to turn inward even more and engage with the outside world even less, even as services like Twitter and Wordpress are making it easier than ever to build a platform for sharing your research.

The unfortunate reality is that for most graduate students and even tenured professors, very few people will ever read your research—and that’s even if you make it accessible by putting it up online, or lucking out with a published monograph. Research, as it’s conceived today, seems to be more about proving your chops to a small circle of peers than contributing to a larger discourse. Maybe it’s always been that way, but I’d like to think that a lack of civic engagement shouldn’t be treated ‘a feature, not a bug’ of doing academic research, particularly since most of us are being funded by tax payers and donations. More selfishly perhaps, putting your research up online is a good way to get your name out there and find that circle of peers who really do care about what you’re doing, whether that’s in academia, or translation, or journalism, or something else entirely. Thanks to my blog and the database of cartoonists I’ve been building under the banner of The Encyclopedia, I’ve been able to get to know the dozen or so people who study Chinese comics around the world, in addition to the super-fans and collectors who act as a sort of informal team of research assistants, pointing out cool things I should look into, or sharing their latest flea market finds.

The unfortunate reality is that for most graduate students and even tenured professors, very few people will ever read your research—and that’s even if you make it accessible by putting it up online, or lucking out with a published monograph. Research, as it’s conceived today, seems to be more about proving your chops to a small circle of peers than contributing to a larger discourse. Maybe it’s always been that way, but I’d like to think that a lack of civic engagement shouldn’t be treated ‘a feature, not a bug’ of doing academic research, particularly since most of us are being funded by tax payers and donations. More selfishly perhaps, putting your research up online is a good way to get your name out there and find that circle of peers who really do care about what you’re doing, whether that’s in academia, or translation, or journalism, or something else entirely. Thanks to my blog and the database of cartoonists I’ve been building under the banner of The Encyclopedia, I’ve been able to get to know the dozen or so people who study Chinese comics around the world, in addition to the super-fans and collectors who act as a sort of informal team of research assistants, pointing out cool things I should look into, or sharing their latest flea market finds.

My own concern is that it’s getting harder and harder to get people excited about Chinese books, movies or comics unless they are ‘banned in China.’ This lack of interest in apolitical narratives, or one which fall outside the narrowly defined concept of dissident literature means that people aren’t really engaging with China in a way that allows them to understand what is actually happening in the country today. It’s very different from the way we engage with, say, Japan, where famous publics figure abroad, like Haruki Murakami and Hayao Miyazaki, are also popular figures in Japan, too. When Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, I think the response in China was similar to how most Americans would respond if Noam Chomsky had been awarded the same award—not so much shock or disbelief as Googling “Who is Noam Chomsky?” The situation is obviously different because Liu Xiaobo is in prison and his writing is banned (and web searches of his name blocked), whereas Chomsky has thankfully been able to enjoy a successful career as a linguist and somewhat less successful one as a social critic (apathy being the American corollary to Chinese censorship), but the point still stands, I think. Or in literature, just look at the way Mo Yan was criticized following his Nobel win. A total disconnect between China and the rest of the world makes solving tough issues like global warming and rising income inequality that much harder, because we have so few common points of reference.

The good news is that there are signs that this distorted view of contemporary Chinese culture as a banned : collaborator binary is slowly giving way to a more nuanced one the reflects the reality on the ground. Ken Liu and Joel Martinsen’s translation of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, for example has been making waves with Anglophone sci-fi fans, becoming a rare example of a translation (from any language) cracking the bestseller lists. Both Liu and Martinsen have been tireless promoters of Chinese culture and literature abroad, with Liu authoring dozens of short-stories and now novels inspired by Chinese mythology and his own experience growing up American but still rooted in Chinese language and culture. Martinsen meanwhile, is famous in the China-watcher community for the work he did on the blog Danwei.org, which he cofounded with Jeremy Goldkorn and has since transitioned into a consulting firm. He also spent more than a decade of his life living in Beijing, and has some really interesting perspectives on the reception of North American culture in China. I can’t say that The Encyclopedia Manhuannica has had nearly the success of either of these projects (not being one-tenth as talented or hardworking as Ken or Joel), but hopefully I’ll be able to get there eventually if I keep at it.

You’ve done research on the history of the Shanghai Manhua Society, an important group of cartoonists who came together in Shanghai in the mid-1920s. Can you tell us more about this for those who have not heard of them?

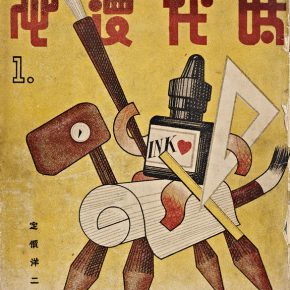

The Shanghai Manhua Society was a group of like-minded young men who shared an interest in drawing cartoons and comics. They were one of many such groups that formed in Shanghai and other Chinese cities around the turn of the 20th century—more famous examples are the League of Left-wing Writers, the Sun Society, and the Creation Society, focusing on politics and literature. There were also groups for painters, like the Heavenly Horse Society, which several of the Shanghai Manhua Society members also belonged to. The Shanghai Manhua Society is credited with popularizing the term ‘manhua’ to mean ‘cartoons’ or ‘comics’ in Chinese. They didn’t invent it, but they co-opted it shortly after it came into vogue and really changed how the word was being used, from the specific, painterly cartoons of Feng Zikai’s rural scenes to a style of satirical and crass of urban cartooning more in line with what was appearing in American and European magazines at the time. Thanks in large part to this small group of about a half dozen core members, there was huge boom in cartoon periodicals in China in the early 1930s. Dozens of new publications appeared with all kinds of fanfare only to go bankrupt the very next month. There were countless challenges involved with getting things printed in China at the time, with severe limitations on what kinds of equipment and materials were available, not to mention having to deal with censorship from both the Nationalists and also the International Settlement authorities, who at one point sued the group for harming public morals after they included a series of nude pictures of ‘Women Around the World’ in their magazine. They’d actually been pulling the pictures straight out of another book, and so, ironically, they ended up getting off the hook.

The Shanghai Manhua Society was a group of like-minded young men who shared an interest in drawing cartoons and comics. They were one of many such groups that formed in Shanghai and other Chinese cities around the turn of the 20th century—more famous examples are the League of Left-wing Writers, the Sun Society, and the Creation Society, focusing on politics and literature. There were also groups for painters, like the Heavenly Horse Society, which several of the Shanghai Manhua Society members also belonged to. The Shanghai Manhua Society is credited with popularizing the term ‘manhua’ to mean ‘cartoons’ or ‘comics’ in Chinese. They didn’t invent it, but they co-opted it shortly after it came into vogue and really changed how the word was being used, from the specific, painterly cartoons of Feng Zikai’s rural scenes to a style of satirical and crass of urban cartooning more in line with what was appearing in American and European magazines at the time. Thanks in large part to this small group of about a half dozen core members, there was huge boom in cartoon periodicals in China in the early 1930s. Dozens of new publications appeared with all kinds of fanfare only to go bankrupt the very next month. There were countless challenges involved with getting things printed in China at the time, with severe limitations on what kinds of equipment and materials were available, not to mention having to deal with censorship from both the Nationalists and also the International Settlement authorities, who at one point sued the group for harming public morals after they included a series of nude pictures of ‘Women Around the World’ in their magazine. They’d actually been pulling the pictures straight out of another book, and so, ironically, they ended up getting off the hook.

The Shanghai Manhua Society founders went on to lead the anti-Japanese propaganda movement, with figures like Ye Qianyu enlisting their peers, and several hundred artists participating at the peak of the movement by some estimates. Because WWII began with the three-month long Battle of Shanghai for the Chinese, the publishing and film industries were especially devastated. Many cultural entrepreneurs relocated to Hong Kong, eventually contributing to the post-war cultural renaissance there in the 1950s and 60s. Most of the Shanghai Manhua Society members had (covertly) sided with the Communists during both WWII and the Chinese Civil War, however, so they largely ended up staying in the PRC, becoming teachers for the next generation of artists who would create the propaganda posters that the Mao-era is so well-known for today, some of which were printed on the same presses that had been used to do the comics magazines before the war. Another really fascinating way they influenced the visual culture of the PRC is via animation—Te Wei, who is remembered as a sort of Walt Disney-like figure, became a disciple of the Manhua Society in the 1930s, and went on to lead the Shanghai Animation Studio until he was ousted during the political shakeups which led to the Cultural Revolution. After he was released from prison in the mid-1970s he eventually was reinstated and continued making films until the late 1980s.

For anyone who is curious about this subject, my MA thesis on the Shanghai Manhua Society is available online, at my blog and also on UBC’s digital repository cIRcle under a Creative Commons license. I mostly cover the founding of the group, but John Lent and Xu Ying have published a great essay on their wartime activities (“Cartooning and Wartime China: Part One — 1931-1945” in Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2008 issue of The International Journal of Comic Art) if you’d like to follow what happened to after the time period I focus on.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of our interview with Nick Stember.