1

The town of Wesleyville lies off the grid. No road signs point in its direction and it has lain empty for decades near the shore of Lake Ontario. It is yet another Canadian ghost town. But the church hummed with life in the humid summer heat, its pews gradually filling up as an expectant crowd filed in. There was a move by an optimistic arts group to fix up the town as a writing and visual arts community, and the church was one of the first buildings to receive a renovation.

Dave Carley apprehensively watched as the reading of his project began. He needn’t have worried. Richard Lee and Chick Reid were not in costume but the reading began smoothly, their acting experience removing the audience from the nave of the old church. A collection of old photographs were being eagerly inspected in the front pews. Meanwhile a woman who had been to Southeast Asia had brought souvenirs along, her collection of carved shields and woven hats out of place in the Ontario countryside.

The play had the elements of a classic fairy tale. A young man with a provincial life tries to understand his past. The answer is complicated, but in short his father is a king in a distant state. He could have been the heir to a throne had things been different.

The catch is that Canadian Rajah is based on a true story. In 1927 the Toronto Star reported that Esca Brooke Daykin, a mixed-race private secretary living at Lawrence Park, Toronto, was in fact the rightful heir to the Kingdom of Sarawak.

2

Sarawak is now part of Malaysia, taking up a substantial chunk of the island of Borneo. But until the 1940s it was a kingdom ruled by English adventurers for over a century.

An adventure-hungry mercenary named James Brooke sailed into Sarawak in 1838, where he promptly struck a deal with the state’s Bruneian overlords. Several years of political maneuvers earned him the title Rajah-the King. Now known as the White Rajah of Sarawak, he eagerly made vast territorial gains, harassing the Sultan of Brunei for more territory while making deals with local allies. Sarawak soon became a haven for foreign adventurers, one of them a nephew who would one day inherit the throne from his controversial uncle.

Rajah Charles Brooke ruled Sarawak for fifty years until his death in 1917. Sporting a glass eye that he picked up from a London taxidermist, he recorded his love affairs in detailed diaries and was fluent in the local languages, often found smoking and socializing with his local soldiers well into his old age. He was survived by his wife, the Ranee Marguerite de Windt, who had a firm foothold in the Sarawak Raj—her books and lectures were selling well and she and her feckless children had all the trappings of royalty.

But all this was abruptly interrupted by Esca’s claim. The historical record was clear enough. Charles Brooke married a native noblewoman named Dayang Mastiah in Simanggang. They had a son named Isaka, later baptized Esca. After Charles left Mastiah he proceeded to marry Marguerite de Windt, a wealthy heiress whose fortune he promptly siphoned away for the Treasury. At around this time Esca was removed from his birthplace of Sarawak as a child, and after a tumultuous journey stretching to England and South Africa he eventually wound up in Ontario as the adopted son of the Archdeacon Daykin. Throughout his life he would retain brief flashes of memories from his time growing up in Borneo.

In Ontario he went to Trinity College School in Port Hope, moved on to Queen’s University, before eventually being forced to take over some of his adoptive father’s work. He first worked as a floorwalker in Ottawa, and then failed at business in Toronto, before becoming secretary to the mining magnate Sir David Dunlap. By this time his foster parents were both dead and he had a family of his own to worry about in the face of harsh anti-miscegenation attitudes in what was then a heavily Anglo-Saxon city. All this while he was uneasy about his heritage and was forced to keep the story of his past a secret except to his family.

It was only when he approached middle age and his own family was well-established that he decided to go public with his revelation. It was a calculated decision that would eventually end in humiliation when the Ranee and her connections snubbed his efforts, turning him bitter and disappointed.

3

Dave Carley is a prolific playwright based in Toronto, having written almost twenty plays that have been produced in Canada, the United States, and other countries worldwide. But even with many accolades under his belt, including a nomination for the Governor General’s award, turning Esca’s tumultuous story into a play proved to be immensely challenging.

Cassandra Pybus’s The White Rajahs of Sarawak, which explored Esca’s story in detail, proved to be a major inspiration. To his surprise it turned out that Esca had lived in Madoc, Ontario, for some time. Carley had been to Madoc many times when he was growing up and the realization that a man who could have been a king once lived there was one of the factors that triggered him to begin work on a play.

In addition to the usual research —scrolling through the internet, examining archival materials, and reading biased “autobiographies” written by the Ranee herself—he had a stroke of luck when Esca’s descendants found out about his project. Two of Esca’s granddaughters proved helpful, especially when the process of writing his play stalled and restarted several times over the years. And once the basic facts were sorted out changes had to be made for dramatic effect—a key element of this play is a fictional meeting between Esca and the Ranee in London in which he fails miserably at getting recognition of his heritage.

Given the fact that he was writing about real people, strict attention to detail was required. Even deciding on Esca’s voice required some thought-ultimately Richard Lee was to speak without an accent to contrast him with the mercurial Ranee’s British accent. One of Carley’s key responsibilities was to understand the motivations driving his characters. The Ranee’s motivations were straightforward: She had a fortune and a family to protect. However, Esca’s own point of view remained elusive. It took further research and conversations with the granddaughters that eventually allowed him to draw an informed conclusion.

“[Esca] humiliated himself seeking recognition because he wanted to make sure his own children were “safe” in white mid-20th century Toronto. If he got recognition, they would then have a family line that was legitimate legally, as well as the gloss of aristocracy. Esca failed but only in that – he had a big, wonderful family, a gorgeous garden in Toronto and a cottage north of Kingston where he happily whiled away his days, fishing, and canoeing. He had a good life, but for the one thing.”

With all the struggles involved in working on the play, most notably trying to find a balance between Esca’s Canadian upbringing and the grip of the Brooke family on Sarawak, Carley almost gave up several times. Ultimately he chose not to involve the colourful Brookes and to just focus on Esca—it was the unwanted rajah’s son who had initially piqued his interest, and the final version of the play was simply the struggle of a man trying to establish his identity. It was elegant and poignant. It was all he really needed to tell.

Given all the effort required to tell Esca’s story, it is not surprising that this project is now in its tenth year.

4

Esca remained attached to his school throughout his life. Trinity College School was heavily Anglo-Saxon when Esca studied there, and Carley noted that he really enjoyed his time as a student. Was it the fact that he was an excellent cricketer, or that he was alone and away from home? Either way, Esca was accepted by his peers unquestioningly.

In one of his letters kept in the school’s archives, an older Esca has just looked through old photographs from his youth. He writes about his current life: he describes recovering from a severe thrombotic heart attack, his passion for gardening, and trouble with his eyesight. He reminisces about steeplechases and cricket. But right at the end his tone changes abruptly. He mentions that the surname Daykin was an invention. He is actually Esca Brooke of Sarawak. He talks about how he was adopted by the Archdeacon Daykin and that his mother died when he was young. He recalls being surrounded by native attendants, unable to speak English when he was first sent away to England, far from the warmth of his tropical home.

His letter ends as follows.

“My half-brother now rules. I enclose stamped envelope of my own Father Sir Charles Brooke. He was a nephew of the first Rajah Sir James. My half brother is the [[?]] millionaire and I am just Esca Brooke. My name came from Whyte-Melville’s ‘The Gladiators’. [Funny the twists fortune flies].

“Our love to that darling wife of yours.

“The best to yourself.

“Most sincerely.

“Esca BD”

This letter was written in April of 1943. A nation on war footing. Japanese Canadians forced from the coast and rounded up in camps. The Brooke royals evacuated from Borneo as the war consumed Sarawak.

Esca died in 1953 and was buried at the Mount Pleasant cemetery in Toronto.

Decades after his death, two of his daughters visited Sarawak, which had gained independence and was now a Malaysian state. Regional newspapers happily ran articles showing the daughters arriving in Simanggang, renamed Sri Aman, to meet with distant relatives. It was a nostalgic throwback to an era that was fast becoming quaint. Newly-minted politicians in the state capital of Kuching found themselves in a country where ideas of racial strife, eroding traditions, and petroleum geopolitics had become their new reality.

5

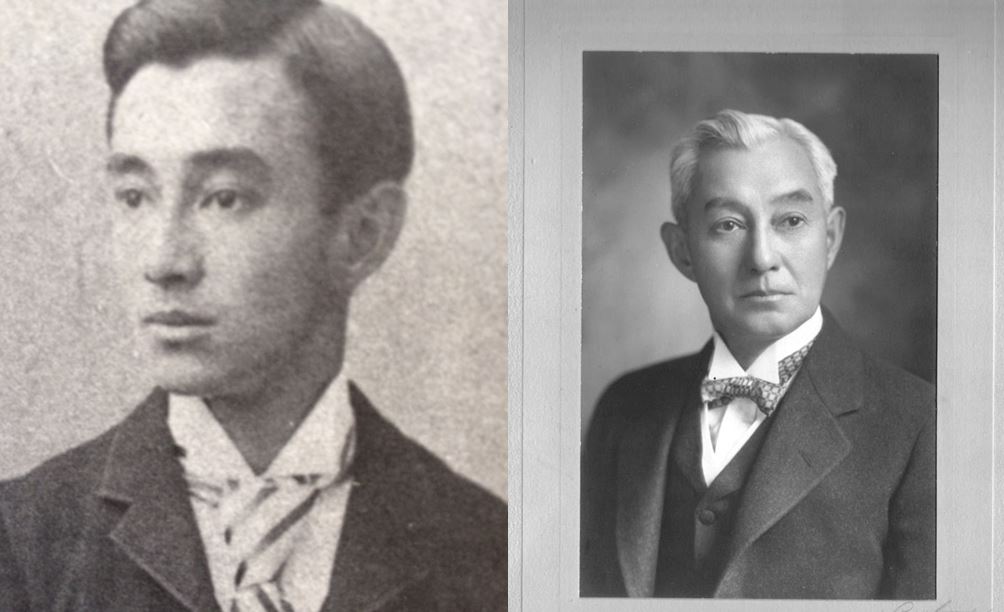

One final note is that Esca was a noted gardener. His garden in Lawrence Park was reportedly magnificent and warranted a mention in the Pybus book. The granddaughters recalled their brother going over to help Esca work on the garden in his youth. Carley hoped to see the garden itself when he paid a visit to Lawrence Park, wandering down the street where Esca once lived. But the new occupants of Esca’s old houses were never in when he made his rounds, and their backyards were out of sight. Perhaps some remnants of Esca’s old garden still remained, but judging from the scale of the renovations it was likely that nothing was left. Traces of Esca’s life were preserved only in memory, his handwritten letters, and the photographs of him staring back at the camera, sharply distinct Eurasian features captured on film.

6

The reading was well received. Carley’s nervousness about how the descendants would react happily evaporated. One of them was particularly happy with Esca’s portrayal, whose photos filled the albums that they had been inspecting in the front pew. That perhaps was the best compliment that he could have received. After a decade of work Canadian Rajah was now edging towards its full production. It will soon be the 150th anniversary of Esca’s birth, and to Carley it was only right that Esca’s story should be premiered in Toronto, his adopted home after a lifetime of struggles.

The guests prepared to depart as the long summer day drew to a close. Darkness. The only lights issued from inside the church. And out of the dusk a sleek black 1935 Rolls-Royce driven by one of the descendants appeared from its hiding place behind the church, its vast headlights gleaming dimly. To Carley it was bizarre and fitting; it was almost as if a rajah was going to emerge from the car.

But the time of kings and empires was long over. The engine of the Rolls came to life and it started out of Wesleyville, vanishing into the night.

Dave Carley’s Canadian Rajah is currently still in production, with a reading scheduled for January 28th (evening) and 29th (matinee) at the Warkworth Town Hall Centre for the Arts. Since Richard Lee will be with a production of Kim’s Convenience, and the play will be headlined by Jon de Leon and Chick Reid. For more information on the play, read our follow-up interview with Dave here. This article would not have been possible without help from Dave and Viola Lyons of the Trinity College School. Photographs of Esca Brooke courtesy of Joan Brown and Shirley Cooke.