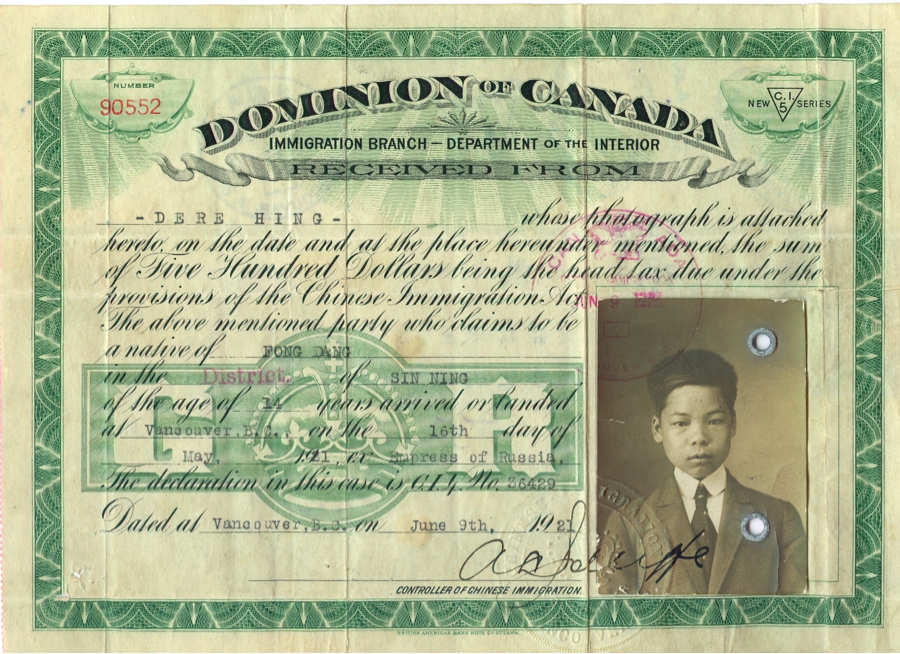

William’s father’s head tax certificate

In 2017, Canada celebrates its 150th birthday. Lesser known, it also marks the 70th anniversary of the repeal of the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, which banned all Chinese immigration to Canada for 24 years. This Act, along with the Head Tax that was imposed on the Chinese starting in 1885, lasted 62 years of Canada’s 150-year history. While we celebrate, we are also reminded that the legacy of racist laws against a community continues long after the laws have been lifted, even at the highest levels of society. Over the years, I’ve tried to tone down my anger against the system, but when this powerful emotion swells up, I try to channel it into positive action.

I am the son and grandson of Head Tax payers. As someone who has dedicated twenty years of my life to the Head Tax Redress Movement, I find that from time to time, I need to remind people in the Chinese Canadian community and Canadians in general of a sad aspect of our past. Many may not share my passion for this history; nevertheless, it is institutional with lasting effects and continues to be present today. I want to give voice to some of those who suffered the consequences of discriminatory legislation and to those who also dedicated their energy to seek redress for the men and women who bore the brunt of early discriminatory immigration policies.

Ng Wing Wah, also known as James Wing, came to Canada alone, at the age of eleven, in 1923. His father left Toishan for Canada before he was born. When he arrived in Canada, they were strangers. The young Wing could never address his father as “Dad” or “Papa.”

“I don’t know why. The word never got past my throat. It was some kind of psychological block.”

His father scrambled to save and borrow the money to pay his son’s $500 Head Tax before the deadline of July 1, 1923 when the Exclusion Act would take effect and no Chinese would be allowed to immigrate to Canada for close to three decades. Mr. Wing went back to China to marry in 1933. But the law did not allow him to bring his wife to Canada.

Mr. Wing was one of the last Head Tax survivors. He was active in the redress movement and campaigned for Prime Minister Stephen Harper to make his apology to Chinese Canadians in 2006. Mr. Wing passed away in 2008; glad of the justice he finally received.

62 years of state racism touched people in profound and lasting ways. It is important to put a human face to those affected. I find it sad that few people are aware of the plight of the women during those years of forced separation from their husbands. The women suffered as much if not more than the men. Known as “Gold Mountain widows” – women left behind in the villages, while separated from their husbands – they had to look after the household, serve the mother-in-law, raise the children and eke out a subsistence survival through farming, all the while expecting the little remittances from their overseas husbands, which sometimes never came.

Mrs. Lee Seuy Toy lived in the apartment next to my mother at the Bo Lai Lo (Residence of Utmost Affection) seniors residence at 990 St. Urbain. She had a group of four or five women friends who got together everyday to chat about their daily lives, hardships of the past, and how their children and grandchildren are doing; and which Chinatown store had the freshest Chinese greens on sale; and how prices have risen so much that they relied on their children to bring them fresh meat and other delicacies. The women gathered together to support each other and to ease their loneliness.

Mrs. Lee married at age 20 and her husband, 30, in 1926. Mr. Lee came to Canada in 1916 and it took him the ten years to pay off the loan for the $500 Head Tax before he was able to journey back to his village. After the marriage, he stayed in China for a year before returning to Canada and he never returned. For the next three decades, the Exclusion law prevented Mrs. Lee from coming to Canada.

In 1955, however, Mr. Lee was finally able to bring his wife to Canada. Her life did not improve by much though, as she had to do most of the work in the laundry and take care of her sickly husband. They had not developed any kind of relationship as husband and wife, being separated for 30 years. Years of working in the laundry gave her thrombosis. When asked how she felt about marrying a “gimshan haak (Gold Mountain man),” she said she could not make a choice of her own. Her parents arranged the marriage. Mrs. Lee burst into tears whenever she talked about her life. She echoed the sentiments of the other elderly ladies,

“In the next life, don’t come back as a woman.”

Mrs. Lee died alone at the age of 94 in 2000. She did not live long enough to receive an apology from the Canadian government.

In her effort to bring these issues to light, Karen Cho made a documentary film in 2004, In the Shadow of Gold Mountain, which was widely shown on the CBC news network. It was also used as a tool in the Redress Campaign in the lead up to the 2006 general elections. Yew Lee, one of the plaintiffs in the 2001 class action court case on behalf of the Head Tax families, gives this impression of the community,

“There were Mandarin speakers (recent immigrants) who saw Karen’s film who were more angry than I was. They see this as their foundation as they moved their families from China to here. They saw our pioneers and how they were actually treated, no wonder they feel the discrimination that they still feel today…The government legislated discrimination had structural ramifications. I think it continues today, although China’s rise to power softens that.”

Simon Wing is eight years younger than me. He is one of the youngest sons of a Head Tax payer. His father, James, was of the generation of my father, so Simon and I shared common experiences that we exchanged over the years. It helped that we both lived in the western part of Montréal and occasionally talked on the train to and from work. As a successful doctor, he was grateful for the hard work and difficulties endured by his parents.

“Before my father bought his house in Cartierville (a working-class suburb of Montréal), he went to see all the neighbours to ask if they had any objections to a Chinese family moving in. No one objected. He eventually lived in that house for almost 50 years, before he moved to a senior’s residence in Lasalle.

When my mother reunited with my father in 1952, it was a very lonely time for her – very difficult. She didn’t speak English or French. It was very isolating. My brother and sister chose to stay behind to contribute to the New China after the Revolution. When she left China, she told them, ‘I’ll be back in 5 years.’ She was overwhelmed by the emotional separation. For the first number of months here, it was really hard for her to leave those two children and she was crying almost everyday. It wasn’t until 25 years later that we went back to see them. She never got another chance to see them again, as she died from cancer 8 years later in 1981.

When my parents and I went back in 1973, it was a very positive experience for me to see my siblings, but there was a sense of deep sadness. Here were these two people so closely related to me by blood, yet I only knew them as a kind of distant cousins, like one would know distant cousins, and how we were separated by politics, of the two worlds; politics of Canadian history and politics through Chinese history, that had kept us apart all these years. My brother lives in Szechuan and my sister lives 1300 km away in Guangdong. So in a way, the three of us feel that we’ve been dispersed.

An important element in this separation was the Exclusion Act, which prevented my father from bringing his family to Canada after he married in 1933. He couldn’t even consider bringing his family to Canada until after the law was repealed in 1947. I went back to see my siblings again in 1985 and a few more times since. They’ve come to Canada to visit, too. In our whole lifetime, we’ve spent about three months together.

My father was a positive man. I have incredible admiration and respect for him. One of the things that really impressed me was his tenacity. He went through many years being separated from his whole family – 10, 15 years. This is something that I could never imagine or even consider. What was amazing is that whatever those experiences were, he always came through without any real bitterness or rancor. He continued to live life with a very positive outlook towards the future.”

–

The stereotyping of the Chinese in Canada seems to be ingrained into the Canadian state apparatus. It has been 70 years since the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, however, Canadian attitudes to the Chinese are still somewhat shaped by the institutional exclusions imposed by the state. Going back 15 years, June 10, 2002 there was an obscure “incident” that happened during the appeal, to the class action case on behalf of Head Tax payers, spouses and descendants. The original case was dismissed and the plaintiffs decided to appeal to the Ontario Court of Appeal. In her paper, “Playing Second Fiddle to Yo-Yo Ma,” Avvy Go, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs, cited one of the appeal judges, the Honourable Justice James Macpherson, as he spoke in court:

“The Chinese head tax payers were happy to be here and had already received redress through their ability to remain in Canada… The fact that the head tax payers and their descendants are still here is redress enough… Paying the head tax is made all worthwhile when one can see their granddaughter playing first string cello for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.”

Here are Avvy Go’s impressions on the event:

“While Ms. (Mary) Eberts, the plaintiffs’ lead counsel, was trying her very best to point out to the learned judge that his comments were nothing more than “happy immigrant” stereotype, the other counsel, yours truly, a Chinese Canadian immigrant, was in so much anger that I had to control my urge to start screaming at the top of my lungs as if in doing so, I could make the judge understand how much his words were hurting me and the people in his courtroom.

As if it is not enough to simply reject the Plaintiffs’ claim for redress, they have to be told that they are – and have always been – in their rightful place in society. They have to be reminded that they must be grateful to their government…for what they have – even though whatever they have accomplished is not a result of, but is in spite of, everything the government has done for them.”

On the “Model Minority” syndrome, Avvy summed it up very succinctly:

“The notion of model minority that is so often applied to Asian Canadians in general and Chinese Canadians in particular is effectively used by the judge as reason for disputing any Government’s obligation to redress past wrongs. Because Chinese Canadian immigrants are doing well today, so the arguments goes, therefore any wrongs that have been committed against them in the past can and should be forgiven.

If Chinese Canadians were indeed doing well, perhaps it would have been easier to swallow this line of reasoning. But the reality is much different from the myth. But just like all immigrants of colour, many Chinese immigrants are struggling in low-waged, non-unionized jobs. Those who came with professional background and post-secondary education are unable to practice the professions that they are trained in because of systemic discrimination in the Canadian job market.”

The Chinese Canadian National Council lodged a complaint to the Canadian Judicial Council against Justice Macpherson for his remarks. The complaint was closed or dismissed by the Council.

There are structural ramifications of government legislated discrimination. There are popular attitudes towards Chinese Canadians, still seen as immigrants, even from a learned judge. There is the stereotyping in the media and systemic disrespect. It is no wonder that it took a generation – 22 years from the start of the redress campaign in 1984 until the Apology in 2006

Kenda Gee, Chairperson of the Edmonton Head Tax and Exclusion Act Redress Committee, and a stalwart in the redress movement had this to say about the long-term effects of the government legislation against the Chinese in Canada:

“The devastation of not having women in the community – your mothers or sisters or daughters – and the separation from your dads, you can’t even express it in words. My relationship with my dad is not “normal.” The relationships between the generations are so utterly different than most other communities in the country. But I would even go as far as to say that not having any female element to social development, just doesn’t devastate one generation, you are talking about several generations. You just don’t recover in one generation. As a result of the social exclusion that did not allow us to integrate, despite having bee here for three generations, we only have the first generation going to university.”

Canadian history is full of racial and social oppression and if we don’t deal with past and present oppressions and eliminate and redress them, we will continue to maintain those oppressions. Prime Minister Harper apologized in Parliament to Chinese Canadians on June 22, 2006 promising partial redress. When he came to power in February 2006, 785 Head Tax payers and widows who were alive were compensated. However there are still 12,000 Head Tax families who have yet to receive redress because these Head Tax payers or their spouses did not live long enough.

Sixty-two years of state racism does do something to you.

William Ging Wee Dere is a Toishanese Chinese whose family endured the racism of the Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act. For two decades, he was a community activist in Montréal involved in the Head Tax Redress movement. In the fine tradition of Chinese Canadians, he worked for the railroad until his retirement. After which he wrote Red China Man – his memoir of political consciousness, activism and the search for identity and belonging – due to come out some time this year.

3 comments

Hi,

My name is TK Matunda. I am an associate producer on the CBC 2017 digital team. I really loved the piece William Ging Wee Dere wrote for you. Would it be possible to get in touch with him about an interview?

Thanks,

TK

Hi TK,

We are thrilled to hear that you enjoyed the piece and I am sure he will be delighted by your interest. I’ll connect you two right away.

Hello,

I would like to have a conversation with William Ging Wee Dere as I am working on a project for high school students that will talk about the diversity of Quebec society and the contributions the Chinese community have made here. Would it be possible to make a connection with him? Thank you