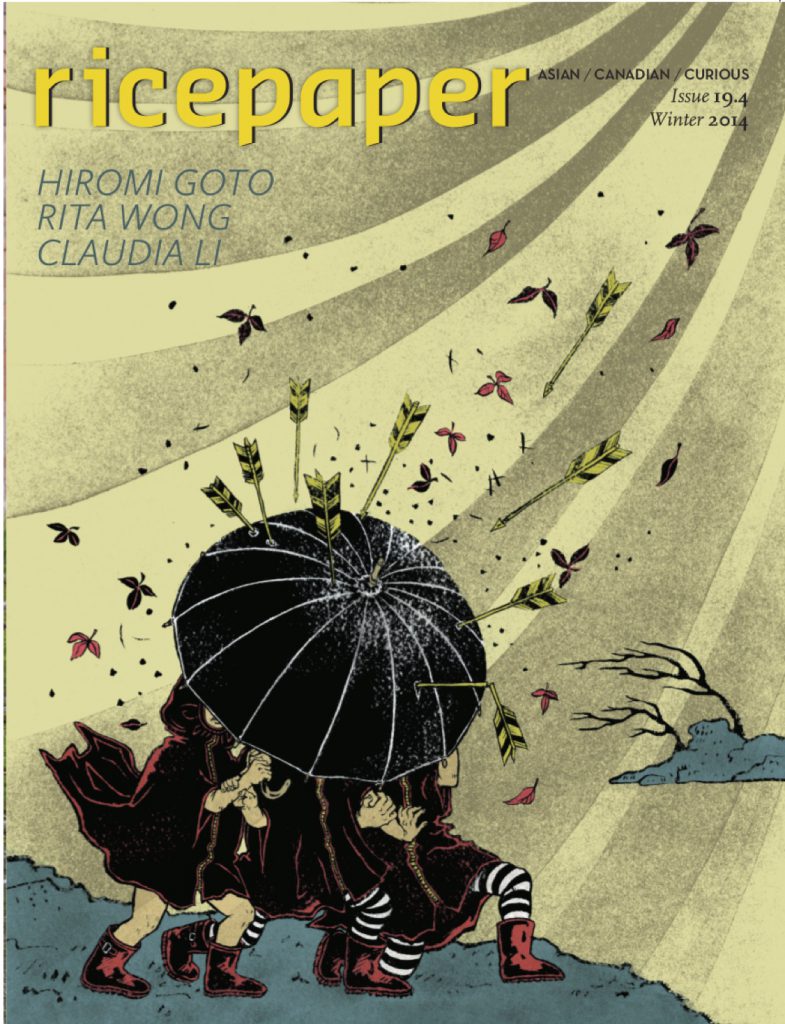

Written by Hiromi Goto (from Ricepaper issue 19-4, Winter 2014)

Written by Hiromi Goto (from Ricepaper issue 19-4, Winter 2014)

Story is what has brought me here today. Story is what has brought you here. We are alike and very unalike in many, many ways. Our bodies, our genders, our sexuality, cultural and historical backgrounds, class, faith, atheism, migration, immigration, colonization, have had us experiencing our lives and our sense of place (if not home) in distinct and particular ways. These differences at times can divide us. These differences can be used against us to keep us divided. But here we find ourselves. Look around you. The faces of friends and the faces of strangers. We came here because of story. There is much power in story.

When I had my first nervous breakdown (I’ve only had the one, but having one when I thought I never would has opened up the possibility that I may have more, although let-the-spirits-see-me-through-the-rest-of-my-life-without-a-second-one!), I finally got into low-budget subsidized counselling after a year on the wait-list. I have no true objective sense of what I’m like as a client. (Am I a client? Not a customer… I wouldn’t call myself a patient. Impatient, maybe.) Probably I was stiff and rather reserved. I spoke like Spock for several months. “Why do you talk like that?” my counsellor once asked me. “Like what?” I said.

During one of our sessions I mentioned how I was very upset with someone who had called me controlling. “I don’t have control issues,” I claimed. “No more than anyone else,” I amended.

“I see a lot of artists,” my counsellor said. “Artists and writers have to control their medium, don’t they?” she said.

Spock changed the subject.

We came here because of story. There is much power in story.

Numerous years have passed since that exchange and I can now concede that in writing stories I control what goes into them. At the same time, I’m informed by the world around me, and my first readers and editors have significant influence during the editing stage of the publishing process. Once the book is published I have no control over how my stories are read. I can only hope that the content and the techniques I used (a form of control) have rendered a story that is near to what I had intended.

The best of stories I have read have led me to places I would not have journeyed on my own. Trapped within my own subjective reality, I’m often confounded by the limits of my own thinking. I would like to be able to surprise myself, but I rarely do. I’m always utterly aware of what I think, if not why, and the banality of my own patterns can fill me with dismay. Of course I experience wonder in my engagements with other people, or in my interactions with nature or art, or music. But my own consciousness can begin to sound like Marvin the Paranoid Android. Not so much because I have the brain the size of a planet, but because I’m trapped within my own conscious self-consciousness.

What can a body do? We can read…. Stories are powerful devices. And, like all powerful devices, they are capable of doing great harm as well as great good. Traditionally published fiction in North America has been predominantly representational fiction. The stories are recreations of known or recognizable elements in our world such as people, animals, plant-life, etc. in an environment be it urban, rural, or “wild,” in some form of interaction that is relational. Science fiction, fantasy, and horror may bring in elements that are imagined, or yet to be invented or discovered, etc. However, the narratives are still informed by a world experienced through a human filter, and, often, the introduction of the fantastic can be a way of better understanding the existing workings and relationships with the experiential world of that moment. The best of science fiction and fantasy can cast a kind of bending light. We see the familiar in unfamiliar ways. We see the unfamiliar in familiar ways.

Writing story is the act of inscribing a specific vision. But in inscribing the specific story she’d like to share, the writer exerts her control. In doing so she eliminates the possibilities of other inclusions. So writing stories can be, simultaneously, an act of creating as well as an act of exclusion.

How important, then, that published stories come from diverse sources; from the voices, experiences, subjectivities, and realities of many rather than from the imagination of dominant white culture. For even as we’ve been enriched and enlightened by tales from Western tradition, stories are also carriers and vectors for ideologies. And the white literary tradition has a long legacy of silencing, erasing, distorting, and misinforming.

Social media has had an effect upon how writers think about representation. Blogs, listservs, Livejournal, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr… sometimes the messages are simple and/or simplistic (how much critical deconstructionist discourse can be accomplished in 140 characters?), but while some of these forms lack in complexity they make up for it in outcomes because of the speed with which the message travels and how many it can reach. There is power in numbers. When enough people are hashtagging WeNeedDiverseBooks there is an effect. Publishers think about ways they can expand their sales. Writers who haven’t much thought about diversity begin wondering what it’s all about. They begin to research and reconsider. Writers who have been writing stories with diverse subject matter and subjectivities raise their fists high in the air and shout, YES!

For even as we’ve been enriched and enlightened by tales from Western tradition, stories are also carriers and vectors for ideologies.

Readers and fans now have the capacity, in ways they’ve never had before, to effect change upon what kinds of stories will reach the public sphere. The one-way control that traditional publishing has held is being eroded by the needs and the desires of a reading public that will not be defined by an older colonial ideological imperative. Diverse readers are demanding stories that represent far more than white middle-class North America. We want and need narratives of diversity not just set in our present, but in our past and far, far into the future. And not only because these narratives are in short supply, but, more importantly, these inclusive tellings are a part of everyday reality for everyone. This is realistic representation.

Much of my writing has been informed by a keen understanding of missing stories. One of my rather simple strategies has been to people my stories with main characters of, primarily, East Asian descent, from a North American context. Mainstream publishing does not in any way reflect the actual demographics of our society. And for such a very long time.

My first novel was a heartfelt roar against a lifetime of experiencing the effects of distorted renderings of Asian women in North American popular culture. I was taking control of my own representation, on my own terms, in my own language.

It matters who and what is being focused upon in fiction. It matters who is creating a fictional account of these tellings. I don’t think the “burden of representation” rests upon the shoulders of those who are positioned as underrepresented. If this were the case we would fall into an essentialist trap that would serve no one well. However, I’m okay with saying that it is my hope that white writers who are interested in writing about cultures and subjectivities outside of their own consider very carefully:

- how many writers from the culture you wish to represent have been published in your country writing in the same language you will use (i.e. English) to write the story,

- why do you think you’re the best person to write this story

- who will benefit if you write this story

- why are you writing this story

- who is your intended audience

- if the people/culture you are selecting to write about has not had enough time, historically and structurally, to tell their story first, on their own terms, should you be occupying this space?

Stories are wondrous devices. They can serve as time travel modules as well as being the most perfect empathy-generating operations with holographic capabilities. Stories can create imaginary simulations of experience so rich and dense they can feel like they are your own. We can live and die, mourn and rejoice; we can feel affinity for a fictional character in a more intimate way than we can feel for our dearest friends and lovers, because we are allowed access to a character’s mind. Fiction can sometimes feel more real than our lived lives, if only in that moment of intense connection, when our physical world slides away and the words cast another before your mind’s eye.

This magic is not a bubble world that exists in a neutral space. The magic was wrought by the author who has a connection to the world she was born into, and she consciously and subconsciously carries those relationships into the story.

The second stage of relationship can be found inside the story—the relationships between characters and their settings as written by the author. The relationships between the fictional elements are modified representations of what the author knows and/or imagines. Writers are creating semblances of relations in order to create a simulation for a particular effect.

The third relational moment is when the reader connects with the narrative—when she willingly suspends disbelief and accepts the story experience into her consciousness. At that moment the reader is engaged in a relationship with the writer, mediated by story. The writer has guided the parameters of the relationship, but she never has absolute control. The reader always has the power to terminate the relationship at any time by closing the book. The reader is not a blank slate of appreciation. The reader brings with her her own experiences of the world she lives in and this mediates her understanding and appreciation of the text.

Finally, when the story has been read and integrated into the reader’s understanding, she carries that experience and learning back into her own experiential world, a little changed, perhaps, and it may affect her own interactions with people in her life.

Imagine this happening one hundred times. A thousand times. Ten thousand times. A hundred thousand times….

I was taking control of my own representation, on my own terms, in my own language.

Stories are powerful engagements.

If you are writing stories with the intention of dispersing them to a wider public how great is the responsibility that is placed upon your shoulders? No one has enlisted you to take up this responsibility. In the moment when the writer decides she will share her story with others she has willingly engaged in an action that sets off vectors of expanding relations that move both forward and backward into time. For just as the writer has ties to lives, communities, history, the future, so, too, do the story and the readers who will interact with the representation.

This level of responsibility can be paralyzing. How can we ever know enough, be mindful enough, to be able, at the very least, to do no harm to others? How do we dare place words in the mouths not our own? Who am I to embark upon this engagement when what I know, what I have experienced, is such a tiny mark upon this planet?

Silence. In the space where your voice would have rung out with its distinct articulation. The moment you silence yourself a gap opens up, and someone else who may have no qualms in occupying that space, will leap in to speak out on their own terms. If you’re a writer (a dreamer) from a people, a community, a history that has been long-marginalized, silenced, or misrepresented, we so desperately need to hear your story in your voice, in your own grammar of perception and articulation…

When the seed of desire to write stories first began germinating inside my chest, I did not think about control, representation, ideologies, power systems, colonialism. I was a lonely child who was much confused by the workings of a hypocritical adult world, where adults said one thing, then did the opposite. Where the people who said they loved me were also the people who hurt me the most. Where school was a blur of confusion, and uncertainty sat with me at the kitchen table every single day. I was in grade three or four when the confusing array of consonants and vowels transformed from syllabic syncopation into the English language. I could read. And, suddenly, I could fly…

Flight is a crucial survival technique. For all that we imagine otherwise, without our weapons we are not an apex predator. Our nails are soft. Our teeth blunt. Our skin easily pierced. Children and women feel their vulnerability most keenly. I was child growing up with Christian parents who loved me, but they were also dysfunctional. The rod was not spared and we were not spoiled. Any stability to be found was provided by my grandmother. But she was also an older woman, living in the home of my father. She was also a person of her generation, and a part of the administration of punishments for bad behaviour.

I was a lonely child who was much confused by the workings of a hypocritical adult world, where adults said one thing, then did the opposite.

“We got in trouble so much,” I once said to my sister. “Why were we always in trouble or afraid that we were going to be in trouble. How bad were we? I don’t remember. It’s all a blur.”

“We were being children,” my sister said.

Reading provided an escape from the confusion of the adult-ruled world around me. Stories transported me to places far from home, where I could feel with my entire being, infused with passion, suspense, adventure, love, longing, magic, without there being a risk to my core self. I could feel without fear. Stories allowed for an engagement that opened my young sensibilities to experience a wider world, a wider imagination, a nuanced and subtle emotional range that could not be safely explored from inside my family dynamics. These childish explorations I embarked upon in fiction can be said to be controlled environments. I did not know this then. When I was a child I thought as a child, so my emotions were simple but keenly intense in that way children are capable of feeling. Reading allowed me to explore an emotional landscape that ranged far and wide, and this was possible through the growing powers of imagination. The more I read, the more my powers of imagination developed.

When I became an adult and a writer I thought as an adult, with a wider range of historical and cultural contexts to understand the complicated world in which I lived. I could identify the oppressive systems that are used to govern and control, and I could think of ways I could destabilize these forces, in small ways, through actions. In my writing I could shape different kinds of story structures, cast focus upon different kinds of heroes, and illustrate dynamics that imagined alternate ways of understanding power and conflict. I thought as an adult, and wrote as an adult, but I did not put away all the childish things.

Reading provided an escape from the confusion of the adult-ruled world around me.

For all that vast swathes of my childhood memories that have been lost or buried, I have not forgotten the sweet pain intensity of emotional engagement that can be felt through story. This is a feeling I still experience today. I have kept these feelings intact. Just as I have carried my imagination, or my imagination has carried me, from my childhood to where I am today. Here. In this very space in time. A brief and miniscule moment in the great vast stream of the universe. An engagement between friends and strangers, bridged by words, carried by story.

There is a Japanese term: kotodama. Word spirit. When you invoke a word you animate it. It becomes. We see echoes of this in other religions/philosophies. I.e. the word is god. When writers try to imagine different ways of engaging, humans to other humans, humans with aliens, humans with animals, all these different relationships, we can make possible new kinds of engagements. To bring stories alive in this way is to try to make change in the workings and fabric of our world. If something is not of this world already, it first needs to be imagined. After it is imagined, it needs to be shaped by the parameters of language. And in writing, in the utterance, the story can begin its life. It can become.

And so we begin. With each telling. With every retelling. A slight skewing of the familiar toward a different plane. The perspective shifts and the way the light falls upon the world casts it anew, ripe with possibility.

Excerpted from Hiromi’s Guest of Honour Speech from the WisCon28 Conference. Reprinted in Ricepaper’s Winter 2014 issue (19-4) with permission of the author from her blog, www.hiromigoto.com.