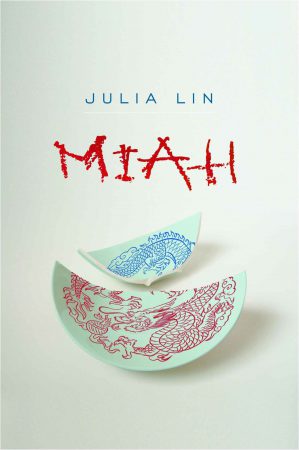

Miah from Mawenzi House Publishers

Written by Anna Wang Yuan

I was born in China and immigrated to Canada in 2006. In 2012, I went back and lived in China for another three years as a Canadian expat. Every three months during that first year, and every six months in the last two, I had to exit and re-enter the country because a visitor’s visa only allowed me to stay for so long. These travels left me displaced in a strange mélange of exile, nostalgia and belonging, continually stuck in a toxic quandary about who “us” and “them” really were. In the midst of the mess, it was thrilling nonetheless to realize that I had transcended the concerns of the physical and begun to, for the first time, question my identity—something unthinkable had I remained in my homeland.

This complex confluence of experiences came to mind when reading Julia Lin’s short story collection Miah. The book’s pieces are linked by an urgent quest for identity—one that develops from the first page to the last. It opens with its titular story in which Tracy, born to a Taiwanese mother and Canadian father, embarks upon a trip from her home in Vancouver to Taiwan to attend her grandmother’s funeral. The trip finds Tracy digging deep into the history of her maternal family, the Huangs, whose patriarch was born in 1885 in a remote village in southern Taiwan. Tracy’s journey of discovery advances in time and pulls away from the south until it closes with a story entitled “Gentle Warriors” in which Tracy, in present-day Vancouver, is struggling to reconcile with the economic and emotional damage done by a new immigrant from China, one of those “Mainlanders.”

The book’s pieces are linked by an urgent quest for identity—one that develops from the first page to the last.

I grew up as one of those Mainlanders in communist China in the 1970s. I remember being constantly told that people in Taiwan were living in abject misery under Kuomintang oppression. I’d never questioned it until the 1980s, when I got my hands on some Taiwanese literature. I found out, via The Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao and the romance novels of Chiung Yao, that Taiwan was far more urbanized than we were. Even “The Butcher’s Wife” by Li Ang, set in a grim, primitive, enclosed rural community that could well fill the bill of my dated vision of Taiwan, refused to fit my perceptions. The story’s fierce feminism was radically ahead of its time and absolutely blew my mind. I never thought of Taiwan the same way again.

During my three-year sojourn in China from 2012 to 2015, I traveled to Taiwan three times. Traveling to Taipei from Beijing was tricky in terms of their overall political relationship. China still claims Taiwan as part of its territory, but flying from Beijing to Taipei counts as going to a foreign country for immigration purposes, which enabled me to reset my residency record. I thought the whole thing was hilarious. When I showed my Canadian passport at the National Central Library of Taiwan, and was granted a day-pass, I was determined to fully absorb the experience of reading Taiwan’s history from the perspective of a Canadian citizen; I would forget what I’d been told and start fresh. However, I’m a user of simplified Chinese, and the library catalog was arranged according to the specifics of traditional Chinese characters. Needless to say, it was a bit difficult. Never had the strong relationship between language and identity been more clear.

In Julia Lin’s stories, language often functions as instrumental in establishing her characters. A trip back to Taiwan helps Tracy brush up on her Taiwanese. In the title story, “Miah”, she repeatedly hears the word “Miah” (means “fate” in Taiwanese) in the conversations with her native Taiwanese relatives. Tracy’s grandmother, living to ninety-three years old and having five sons, was referred to as having a hoh miah (good fate). Her fifth uncle however, committing suicide to protest Kuomintang’s persecution, has a pi miah (bad fate). Later on, in the story “The Colonel and Mrs. Wang”, Lin expertly outs Mrs. Chang and Mrs. Wang as Mainlanders (guah seung lung) by having one say “such a bad fate” to the other. When moving through time and place, it is inevitable that one also moves through languages. Perhaps Julia Lin derives her acute sense for the finer points of languages from her experience as an immigrant?

I remember being constantly told that people in Taiwan were living in abject misery under Kuomintang oppression. I’d never questioned it until the 1980s, when I got my hands on some Taiwanese literature.

A later piece entitled “Departure” traces the series of names bestowed unto Tracy’s grandmother. Born Bai Wen-Hong and called Ah-Hong in her youth, she marries Tracy’s grandfather as his concubine. Although she gives birth to five sons and one daughter, she is deprived the right of being called “mother” by her own offspring according to her husband’s wife’s injunction. In a surprising turn, Ah-Hong’s children start school during the Japanese occupation. Her children are taught by Japanese schoolmasters to call their biological mother Okasan (Japanese for mother). When her first grandson is born, she is addressed from then on as Ah Mah (Taiwanese for grandmother). She has finally gained sizeable respect in a patriarchal village for her lifelong contribution to the continued blossoming of the family tree. Years later, Ah-Hong arrives in Vancouver to live with her daughter’s family. Her son-in-law, whom she had only met briefly in Taiwan long ago, addresses her as Okasan; a cruel reminder that despite her sacrifice, Ah-Hong has never been called “mother” all her life.

In “White Skin,” set in modern, metropolitan Vancouver, a popular destination for foreign tourists, Ah-Hong feels uneasy at a Buddhist temple when she discovers that most of the worshipers are of Japanese descent. Lin’s particular way of looking at the troubled history of the East through the lens of modern-day Canada is a point of view I relate to considerably. However, I felt my sense of kinship with the author lessen slightly reading the closing story “Gentle Warriors.” Tracy loses big money in a real estate deal with a crooked Mainlander. Her mother parrots an old warning to never trust a guah seung lung(Mainlander), to which liberal Tracy responds, “I wish you would stop speaking of people in such racist ways.” Referring Mainlanders and Taiwanese as different races strikes a raw nerve in me. Part of the reason I immigrated to Canada is that I was fed up with having to take sides in massive international political controversies. Be it the issue with Taiwan or Tibet, I wanted to be able to shrug and say, “That’s none of my business.” I could be as aloof as a rock to the current state of the issue, but I found I couldn’t remain cool hearing a Taiwanese person call Mainlanders a different race.

In Julia Lin’s stories, language often functions as instrumental in establishing her characters.

Still, after closing the book, memories continued to surface. I recalled encounters with various Taiwanese people during my trips to Taiwan. One sunny afternoon, I was searching for Gu Ling Jie, the setting of Edward Yang’s film A Brighter Summer Day. A man in his sixties offered his help. He didn’t just point me in the right direction, but led me all the way there. While we were walking, he asked me where I was from. I didn’t want to seem like another ignorant tourist by simply saying, “I’m from Canada,” so I took a split second to weigh my options. But before I could get a word out, he said enthusiastically, “I was from Shandong.” In hindsight, he must be a guah seung lung (Mainlander). What a revelation!

There were also rainy days. Once, at the National Library, I asked a librarian for assistance searching the catalog. I could read traditional Chinese, but I had no idea how to key the characters into a computer. Instead of helping me, she asked gruffly: “Why do you want to read our books? We are different, anyway.” Looking back, I now understand that her intent was to draw a line between “us” and “them,” but as puzzled as I was at the time, I managed to respond, “That’s exactly why I want to read them.” It didn’t help. Maybe it would have helped if I had shown her my Canadian passport? Most likely not. I was still a user of simplified Chinese, which by default made me one of “them.”

A.C. Grayling once said that “To read is to fly: it is to soar to a point of vantage which gives a view over wide terrains of history, human variety, ideas, shared experience and the fruits of many inquiries.” I like reading books that challenge me, as well as each other. Here is an example: Last month, the moment I closed Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness, I was already opening Out of Place by Edward Said. Both authors were born in Jerusalem in the 1930s—one Jewish, one Arabic. Their two books present unique accounts of survival during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Their accounts don’t cancel each other out, but instead, as Grayling writes above, help us soar higher.

When it comes to the unhappy and difficult parts of our history, Tracy’s mother’s motto is “No need to tell” (“Miah,” “Shu”). Obviously, Julia Lin doesn’t agree with her character, and for that I am thankful. When Amos Oz was a child, he wanted to grow up to be a book, because humans die, while books remain. I want to be a peripheral product of a book: its reader. If “reader” can be counted as an identity, I’ll see that I cling closely to it for the rest of my life.

Born and raised in Beijing, China, Wang Yuan had authored four novels and one short story collection in Chinese before she immigrated to Canada in 2006. Her short story collection Beijing Women: Stories was published by Merwin Asia in 2014. She translated Alice Munro’s The View from Castle Rock into Chinese in 2015. Her first article with us, For Whom the Maple Leaves turn Red, is also available on our site!