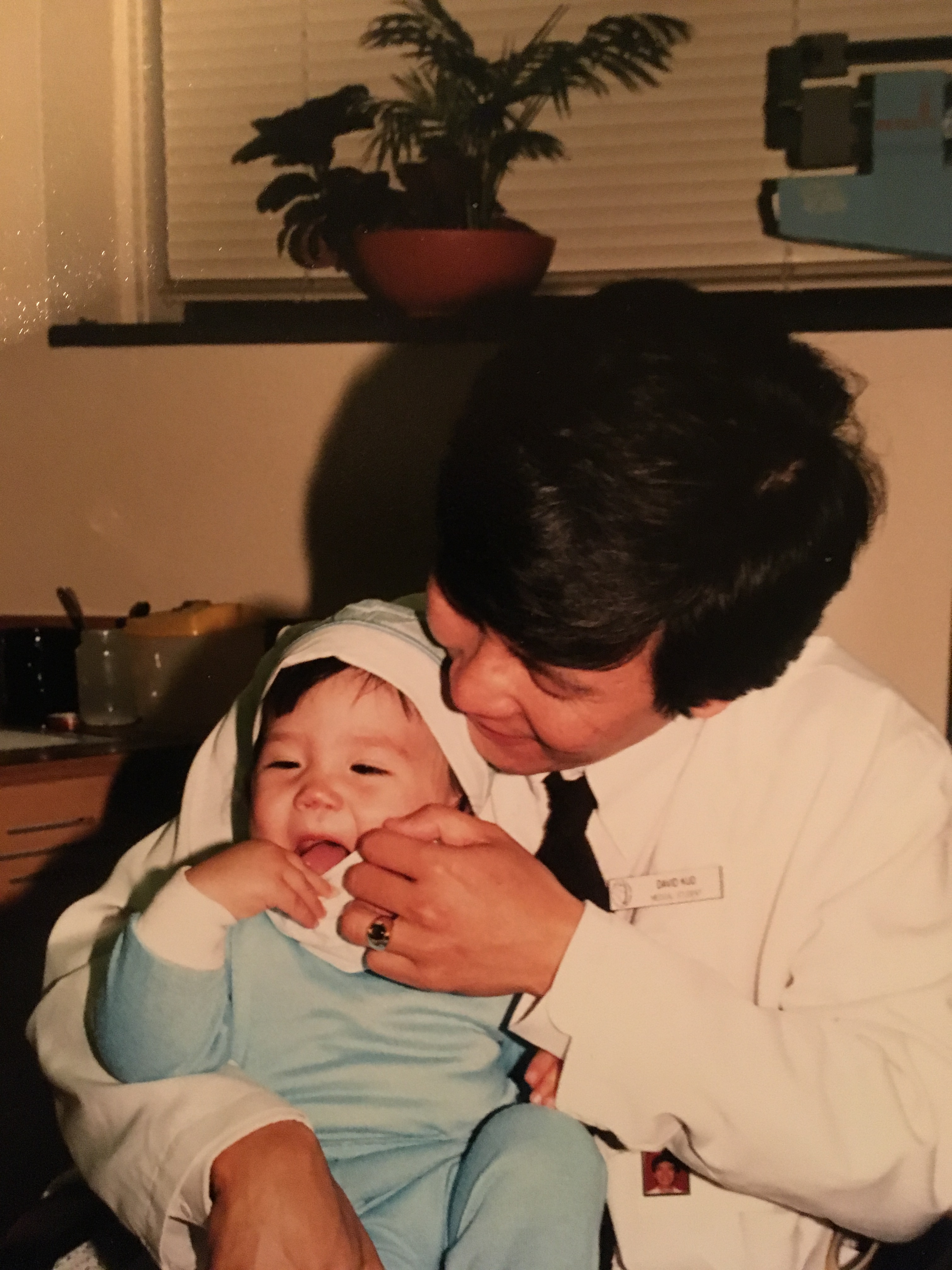

Six Canadians and Americans talk about the awkward, strange, and memorable times they imagined saying or actually said “I love you” to their parents.

Interviews by Pik-Shuen Fung

*Some names have been changed at the request of the interviewees.

Lily*: Saying I love you in Chinese is… it actually gives me chills down my spine. It’s just weird. It’s uncomfortable.

Norris: You know, you grow up in kind of a Western world. All your friends, you hear them on the phone with their parents and they’re always like, “Oh I love you! Oh!” Should I feel bad that I don’t say that more often to my parents? But it’s kind of weird because we don’t really have that dynamic, so I totally understand why it would feel strange to say that to your parents.

Julia*: Do you ever say 我爱你 to anyone? Not really! It’s kind of tacky.

Norris: I’ve never really said I love you to my parents either. They don’t say it to me. It’s weird. I guess we’ve never been used to saying it to each other.

I feel maybe that Asian families, they speak more with acts. It’s more indirect, kind of showing your compassion for someone, as opposed to through verbal means. It’s interesting.

Colin: I remember, one time, getting disciplined for a bad report card that had a C on it. That’s how severe report cards were in my household. Having a C was punishable. And I remember, as I was crying after being punished for it, I was like, “That’s an old report card! You already beat me for that two years ago!” So apparently, he had discovered an old report card and decided I needed to be punished again. In which case, he looked, and then he goes, “Hmm. Okay. Sorry.” And that was the end of that.

Anna: And I think I wanted her to—even if she had her own doubts—to just support me. And just say what moms do, like on television shows. And be like, you know, “I believe in you! You go do it! Even if you land flat on your face, go do it.”

Colin: Even early on, without that being intellectualized, I understood that 不乖 meant “Oh, disappointment, now I’m not being good, now I feel a little bit guilty”. 乖 meant “Yay! I did something right! Now I have their stamp of approval.” So it’s something that I strive for.

Lily: 乖 is basically putting up an image of myself that will get praises from other people. And in order for me to get further praises, then I’ll continue to either get good marks or—I don’t know—just be the ideal person that my parents would think… or the ideal daughter they would want.

Colin: Sometimes that word is used to say, “Oh now you’re obedient. Now you did what I told you to. Now you’re following the rules.”

Julia: My entire life, I’ve been told to be 乖. Be 生性. And 争气.

So to be 乖, is to be good. To be 生性, is to be knowledgeable slash wise, I guess? And to 争气 is to… there’s no real definition for 争气. I’ve put it through a lot of dictionaries. It doesn’t really hit the right spot. But the gist of it is: don’t let other people look down on you. Prove yourself. Is to 争气.

Crystal: So every time I wanted to make big life decisions, you know, of course, not just as a Chinese person, but as a Chinese girl, I would always think: Am I being 乖? Is this the 乖 thing to do? And I used to get really conflicted, and sad, and upset about it because I was like, “Oh shit, I’m being a really bad kid, I’m being a bad person right now.” Choosing to follow my own dreams? What are dreams? Really, I should be fulfilling my responsibilities. And this conflict happens all the time. Still does.

Julia: I remember having to actually write down, in point form, facts to convince my mom to allow me to go to sleepovers.

Lily: I’m not even allowed to have sleepovers. I’m not even allowed to go to someone else’s house. The only sleepover that I had was the one that had to be at my house.

Julia: Oh yeah, that was me too. That was me too. Until I wrote down in point form, and I think I was already 16.

Anna: The way my parents would express love in my family, not just to myself, but also to my siblings, it was never verbal, for sure. And not physical as far as I recall. The constant for my parents as far as expressing love has always been through food. So whenever I get on the phone with my mom, whenever I get on the phone with my dad, one of the first questions will always be, “Have you eaten already? What did you eat today? What have you had? Are you skipping meals?” That kind of thing. That’s always the constant. And I know that is their way of expressing affection, their way of making sure that I’m taking care of myself.

Colin: When the dish is on the table, he would actually pick the juiciest parts, the best parts, and he would give it to me and my sister. And he would preface it by saying, ‘This is what it’s like to be a parent. You give the best parts to your kids.’ Now as an adult, I’m like, ‘Wow, okay.’ At the time, I was just like, ‘Yay! More for me!’ But now as an adult, I really can appreciate that gesture, that very simple gesture. Because there were those few moments where my dad was actually loving. And, I got it. I got it.

Julia: A lot of us Asian kids, we feel we need to be good at school. We need to be the CEO of whatever job we’re working at. Or we just need to excel at whatever we do. And we always need to be doing something in order to be good. We forget that, when we spend all our time being good at our jobs or being good at school, we forget to spend time with our parents. We can’t always just blame them for not spending time with us. And I think sometimes a simple text message, a simple email, or a call to be like, “Hey Mom, wazzup! Okay continue playing mahjong bye.” It makes such a big difference. I think we need to remember that no matter the difference of opinions, and the way—our parents and ourselves—the way we were brought up, we need to remember that they’ve been living their lives many more years than we have. It’s much easier for us to adapt to them. And that they’re getting older every day. So, maybe this is the Asian side of me speaking, but as, you know, the young’uns, we should maybe make more of an effort to show our love to our elders.

Colin: What I’m grateful for, in terms of what my parents did, for me and my sister growing up… I thought an answer would come to me really easily, and I’m having a bit of difficulty focusing on one thing. My thoughts are a little scattered right now.

But what opened up for me in the moment you asked that was, I sometimes don’t think I give my mom enough credit. I think I sometimes give my dad more because he was the provider and he definitely was the more influential voice growing up.

But I also think about how my mom had a lot of anxiety, growing up, but she also had a tremendous amount of courage because of that. Because for anybody else, taking their driver’s test is nothing. For her, it was really, really stressful. It was a really big thing. In fact, she got so nervous, I think the first couple times she took it, I think I remember a story where she went to take the test, she finished driving, she opened the door, and she threw up. It was that big of a deal for my mom to take the driver’s test. Whereas for you and I, maybe it’s annoying—I gotta arrange a car, I gotta take a permit, I gotta take these stupid hours of video before I can take the—but with her it was really stressful. And now that I think about it, I’m actually grateful that she did that because once she had her license, she was able to drive me and my sister around. Whereas before, there were some limitations as to where we could go, what we could do, because, you know, my dad’s working. He’s not going to be driving us around. But the moment my mom became available, that was nice.

But I also think about how my mom had a lot of anxiety, growing up, but she also had a tremendous amount of courage because of that. Because for anybody else, taking their driver’s test is nothing. For her, it was really, really stressful. It was a really big thing. In fact, she got so nervous, I think the first couple times she took it, I think I remember a story where she went to take the test, she finished driving, she opened the door, and she threw up. It was that big of a deal for my mom to take the driver’s test. Whereas for you and I, maybe it’s annoying—I gotta arrange a car, I gotta take a permit, I gotta take these stupid hours of video before I can take the—but with her it was really stressful. And now that I think about it, I’m actually grateful that she did that because once she had her license, she was able to drive me and my sister around. Whereas before, there were some limitations as to where we could go, what we could do, because, you know, my dad’s working. He’s not going to be driving us around. But the moment my mom became available, that was nice.

And now that I think about it, I don’t think she did it for herself. I don’t think she was like, “Yeah, I’m going to get my license so I can drive around town and hit the malls.” I think she really—so there would be another driver in the house. She would do things like take me and my sister to piano lessons. And take me and my sister to Kumon school. This is such an Asian story! Yes, taking us to Kumon school. So, I’m really grateful that my mom was able to have the courage to get her driver’s license with almost the explicit purpose of being able to chauffeur my sister and I.

And I don’t think I ever really acknowledged her for taking that on, and saying, ‘Thank you, Mom, for overcoming your anxiety about getting behind the wheel and being tested, and even throwing up on our behalf, really, so that you could accomplish this. Because I’m pretty sure you did it more for us than you did it for yourself.’ Lord knows she’s not driving now.

Norris: I think if I were to tell my parents that I love them, I don’t know, it would be so weird. So I feel like I would have to have a strategy. Maybe I would bring up this conversation of love in Asian cultures, and why it’s not, you know, a thing, why don’t people say “I love you”, is that how they felt with their grandparents, and have this meta-discussion around it first, and then use that as a way to transition to saying I love them. I feel like that would make it much easier. It’s weird, but I feel like that’s how hard it is to say it. You’d have to strategize, but that’s how you’d say it.

Colin: So I called them, and it was a bit of a stretch, but the first thing I said to him was, “Hey Dad, there’s something really important I have to tell you. Don’t interrupt me. Just let me finish. Because otherwise I may never get to tell you it in the whole, but I just want to tell you that—” Oh! Now that I think about it, I think I might have started with, “I just want to tell you that I love you. I appreciate you and I love you. Because—”

He was miraculously very quiet. He didn’t interrupt me, as he normally does. And I just told him that I am grateful for all the sacrifices and contributions he made in my life. How he came here to this country because he wanted a better future for my mother and myself. And how he brought us over here, and how he did the best he could to always make sure that there was a roof over my head, there was food on the table, he arranged the best education he could for myself and for my sister, and I really acknowledged the crap out of him for all those things. Because I realized, he did some pretty crappy things, but I also never really got the chance to say thank you for all the things that he did that made a positive difference in my life.

So I told him all these things, and also acknowledged how, as an adult now, I understand where his anger was coming from. And it was because he had a painful childhood. As much as I think I might complain about mine, I realized his childhood was infinitely worse. That there was a lot of rejection, and abuse, and pain in his childhood, and that’s why he became the man he was. And of course, as a father I can understand his frustration, and since he was never whole and complete about his own past, he kind of let that spill over onto how he raised me and my sister. But I learned to let go of all that, and came from a place of forgiveness, and openness, and trust, and a place of love, and just acknowledged him, and expressed gratitude for all those things, and at the end of which I remember telling him, “Dad, I just want to let you know I love you.”

And in typical fashion, maybe it’s the Asian parent thing, maybe it’s just my dad, but I remember his reaction being very interesting because he didn’t say I love you back, but instead he said, “Colin, are you drunk? Because you’re talking very funny.” And then he immediately changed the subject about something else.

And here, I’m thinking, wow, he did not, that did not go over the way I expected. So I don’t know whether or not he really understood everything I said, or he just kind of felt it was awkward and kind of glossed it over.

I later found out that he pretty much was happy for the next 24 hours. He was talking about me in a way that was favorable, not as in “my no good son got a B on his report card”, but in a “my son is this, my son is that, he’s a good boy”. Just things that were actually uncharacteristic of me, in terms of how praise, how much praise there was in what he was saying.

So that’s what struck me about the first time—maybe not the first time—but the time I remember most, when I said I love you, and how he responded to that.

**********

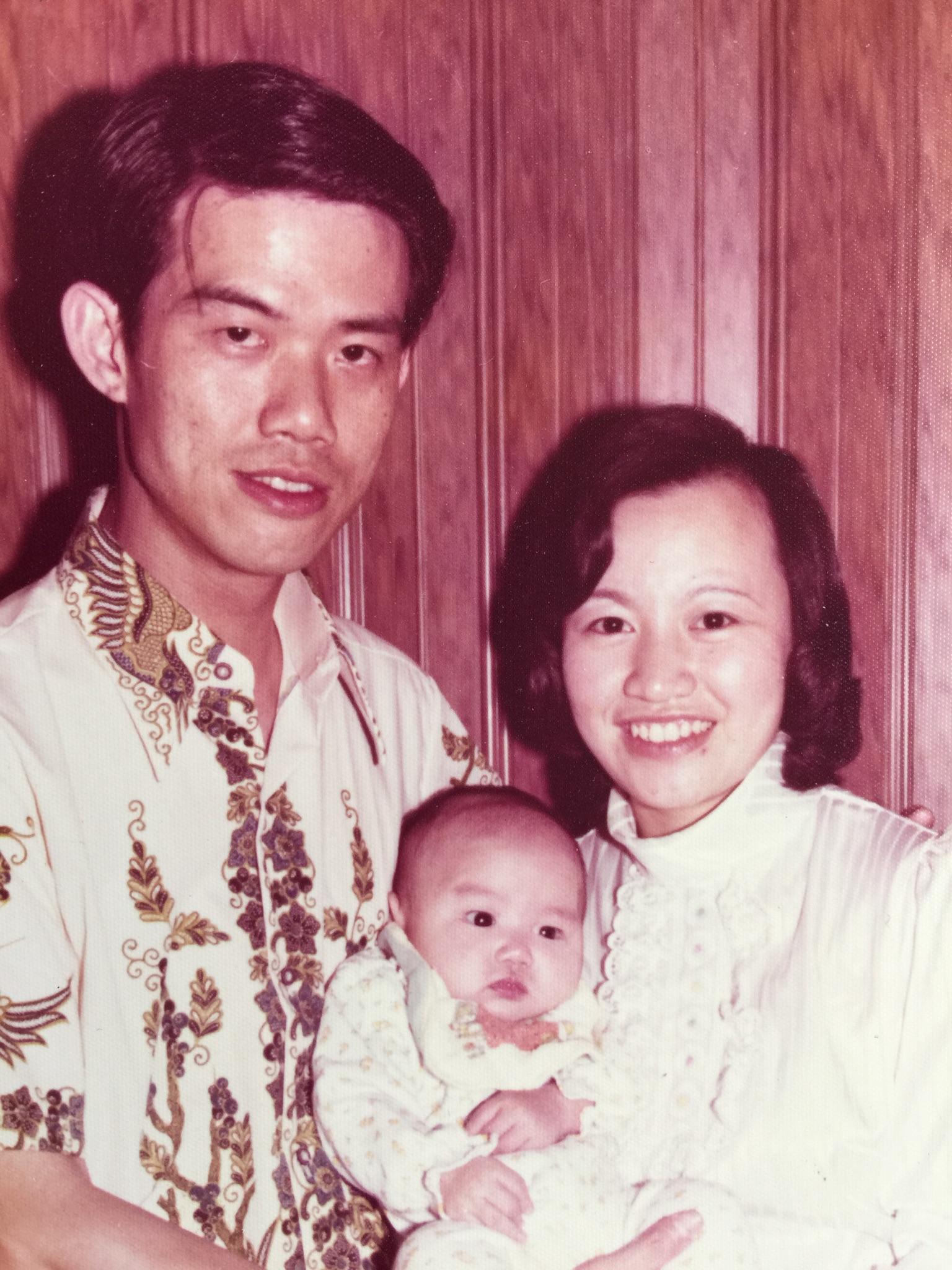

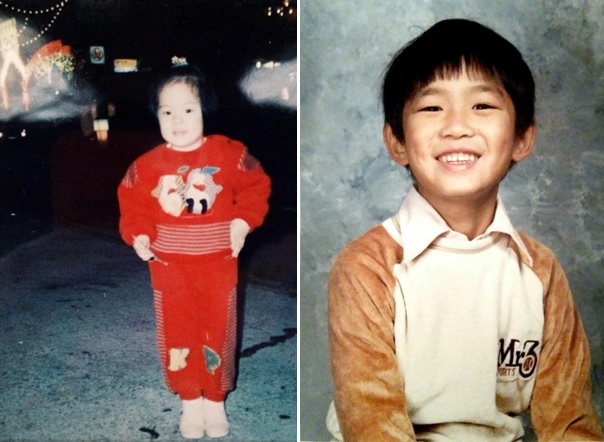

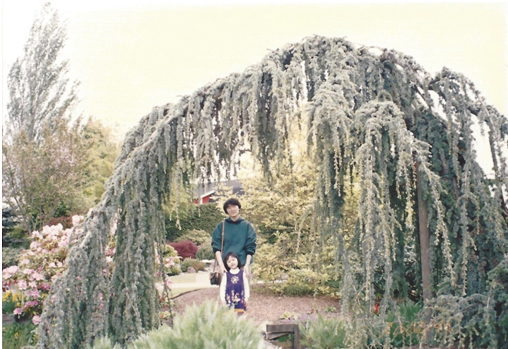

A big heartfelt thanks to everyone who generously contributed their experiences and photographs to this project, including Anna Chan, Crystal Chen, Norris Hung, Alison Kuo, Colin Yen, and others.

Pik-Shuen Fung is an artist and writer born in Hong Kong, raised in Vancouver, and currently living in New York City. Her writing has been published in Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s The Margins, as well as performed at The Frank Institute at CR10 and El Museo de Los Sures. Her videos have been screened at the Newark Museum, Nitehawk Cinema, The Secret Theatre, Beverly’s, and CoWorker Projects.