Image courtesy of the Georgia Straight and Nikki Celis

The following interview took place on June 3, 2014 between Dr. Zhen Liu and Jim Wong-Chu. Liu received her M. Litt degree with her thesis research focus on Alice Munro and her PhD in English Studies from the University of Strathclyde, with the thesis titled “A Liberating Inheritance: Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian Literature, 1970s-2000s.” In 2014, Liu took a research trip to Canada with the goal of mapping out the literary history of Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian literature with the aim of tracing the development of both the literature and diasporic subjectivities. She met with Jim Wong-Chu and the Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop during her time in Vancouver. In 2016, Liu began teaching at Shandong University, China. Her current research projects focus on Asian Canadian children’s literature and Asian Canadian periodicals.

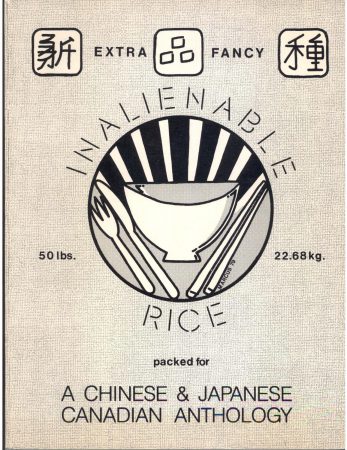

Zhen Liu: Thank you very much for agreeing to see me. My interview today is structured into two parts, about the Asian Canadian anthology that you co-edited and about the Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop Society (ACWW) which you helped found. You are the co-editor for three anthologies and contributed to the first anthology, Inalienable Rice. Would you like to talk about the very first one?

Jim: Yes, Inalienable Rice. That is the first, earliest kind of writing. The idea of making an anthology was actually initiated by the Japanese community. And they were the ones who organized it. But they saw a kind of Japanese and Chinese anthology, so that is why they got us involved.

Zhen Liu: They proposed the collaboration?

Jim: Yes, and that’s when it first happened. Well, because we were doing similar things at the same time. You know, it was late sixties, early seventies, there was an awakening in the communities. Actually what happened was, there was a professor from the US that came up, his name is Ronald Tanaka. And he was quite an activist. He came up and taught at UBC. He was the first talking about identity, identity politics, community, history and so on. I was in the community a lot at that time. I first saw this when some of these people, Sean Gunn, Paul Yee, SKY Lee and many of these other people came down to the community and did an exhibition on Chinese Canadian history. And that was how we started talking about this. And it was very interesting. It was like, wow, something that is new.

One of the earliest Asian Canadian anthologies.

At the same time in Japantown (on Powell Street), there were people that were instrumental, they were also affected by the US, a person named Tamio Wayakama, and he actually marched in the Civil Rights movement in the South and so on. And he was a photographer. He came up to Vancouver and he initiated the first Japanese Canadian historical photograph project. And it came out as a book called The Japanese Canadians: A Dream of Riches (1978), a photograph book about the history of the Japanese Canadians in Canada. It was beautifully done and it was inspiring. You know, something just came out of the blue: those historical photographs that talked about things a lot of people of that generation don’t know about themselves. So that happened simultaneously with what’s going on the Chinese scene.

That was the beginning of the cultural activities. The community began to change at that time, because Nixon went to China and recognized China. Before that, the propaganda was that China was communist and it was going to take over the world. But after Nixon went, all of a sudden things began to change. You know, there were communes, there were “chicks and kids,” everything looks great. The idea of model commune was okay. That began, as a part of the whole movement, of wanting to know more about China. At the same time, the African American movement, you know, Dr. Martin Luther King and black consciousness starting to rise out of the whole idea of civil rights. The Asian American movement followed, the whole idea that we need to create the consciousness to understand our identity, to go back and learn about our history.

Zhen Liu: It seems to me, from the first anthology, there was a conscious effort in shaping a unique Asian Canadian identity rather than Chinese, or Japanese. You were saying that this Asian Canadian identity was created by the third generation?

Jim: Yes, it was a third generation phenomena. The third generation was initially people who were not aware of each other or their own community history. The beginning, from my research, of the Asian American movement, is actually initiated by the Japanese community. It was not started by the Chinese. There was a very famous documentary film called Farewell to Manzanar, in which the Manzanar is one of the internment camps over in the United States, of which we also had several of in Canada. But the third generation, sansei, always heard their parents mention the camps. For them, it was always nostalgic and it seemed, you know, for some third generation who had never experienced the internment camp, they thought that it was quite an enjoyable experience. Therefore they organized a trip to visit this camp. And I think what they saw shocked them, about how badly their parents were treated and the conditions they lived in there. They have barbed wire around them. They lived literally in a concentration camp for a few years. And then the third generation began to realize what happened. Therefore from there there was a beginning of what they called a pilgrimage, an annual pilgrimage, every year, in which they organized busloads of people to go there to experience and to understand what it was.

The younger generation then became very angry. They were angry that they didn’t know, but also angry that their parents were hiding this from them.

Although the parents were not hiding, they were just kind of insulating them from all the pain. There then began an activism—a need to know who are we, what happened and so on. And this activism connects the Asian Canadians with the Chinese American at that time. There was a whole political awakening during that movement, such as the African American movement, and that was when all the stuff started to open up. There was a huge student strike, called the San Francisco State Strike in California, and that was the beginning. That was also when Ronald Tanaka came to Canada from that movement and started the awareness and the whole idea that we need to be aware, that we have to start doing things.

Coincidentally, the Japanese community started to do similar things. But the Japanese were much more articulate than the Chinese, they were just better organized and they were much more methodical and thorough about what they were doing. The quality of A Dream of Riches, I would say is astounding, the quality, the photographs and the words they used to match the photographs are all well made. It was like a landmark. It’s rather stunning. It was just coming out of everywhere. And one of the things we realized that we need to do was put the things into words. That was the part where Inalienable Rice was born. The idea was some of us wrote some poems, some of us wrote some music, and so on. Everybody put what they could together to make this. We have to change how the society sees us and how we see ourselves, and writing is the only way to do it. The stories are so powerful. They also validate people’s experiences.

Zhen Liu: There were some research papers too.

Jim: Yes, anything everybody wrote was put into that. It was really an example of what was in the US. In America some universities helped to publish Asian American anthologies prior to our initiatives. Ours was a response, an actually very modest response because the ones that were coming from UCLA were huge: they had a lot of information. Among the first ones that came out was called Roots. It’s a sort of writing about ourselves, the Asian ethnic minorities. There was a lot of anger. Everything, anything was thrown together, anything that was relevant at all. So it was a response to a time where there was a need to put things into words and to make sense of things. And our response to it was Inalienable Rice. At the same time, people like Paul Yee, SKY Lee went down to the community. They were university students. They came down to Chinatown to look for their identity. They want to find out if they belong and what it is like.

Chinatown seems to be the natural place. In the late sixties, early seventies, Chinatown was very vibrant. Everything was there, a lot of history was still there.

It was a way to get close to the community and get the feeling that you belong to something. Of course there was a lot of politics that was going on. There were always the “two-China” politics – Taiwan and China – and there were all sorts of protests in the community. That was a time when they were also trying to tear down part of Chinatown. So there was always activism and protest that was going on, probably from the early 1970’s to about the middle of the 80’s. It was a time of awakening.

Zhen Liu: How did fiction writing start in the community?

Jim: We were just a bunch of activists. And in some way, it was kind of odd because none of us – the early generation – SKY Lee, Paul Yee, myself and so on – who saw ourselves as writers. We never felt that writing was going to be in our future. We are more activists. It was like, we were sitting having coffee and talk till 12am, talking about what’s wrong, what the community needs, why things are the way they are. We always talked about what’s wrong. Then, at some point, we have to say what if we do something about it. Then the other question that followed was, Why Not? It matters in that we have to do it. Canada is a very unique phenomenon. I think North America is the same, but Canada is very specific about that. In Canada, you are allowed to do anything you want, and say anything you want and you can do anything you want. But if you want it done, you have to do it yourself. The government or people will not do it for you. So you are forced at some point, if you want to prove something or if you want to do something, you have to come out and become active and see it become a reality.

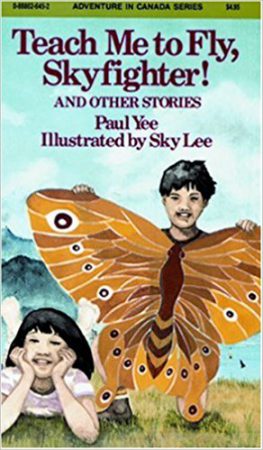

We kept asking questions in the community as we were listening. We were toeing the official line of what the community was dictating. In the meanwhile, there was a need to write. We want to put something down. There was an urge to write. So that was when we started to talk about it. So although the first few of us, there was a person named Rick Shiomi, who is a Japanese Canadian playwright. He was approached by Lorimer, which is an educational publisher, for a children’s book or a young adults’ book, about Chinatown, as one of a series of books they plan to publish. Rick Shiomi was commissioned to do the first. However, Rick just couldn’t commit to it. He just kind of gave it up after a certain point, and asked if somebody else would be interested. And Paul Yee stepped up. That was the first book, called Teach Me How to Fly, Sky Fighter. That was the very first book from the Asian Canadian community and that started the whole writing and publishing movement.

We kept asking questions in the community as we were listening. We were toeing the official line of what the community was dictating. In the meanwhile, there was a need to write. We want to put something down. There was an urge to write. So that was when we started to talk about it. So although the first few of us, there was a person named Rick Shiomi, who is a Japanese Canadian playwright. He was approached by Lorimer, which is an educational publisher, for a children’s book or a young adults’ book, about Chinatown, as one of a series of books they plan to publish. Rick Shiomi was commissioned to do the first. However, Rick just couldn’t commit to it. He just kind of gave it up after a certain point, and asked if somebody else would be interested. And Paul Yee stepped up. That was the first book, called Teach Me How to Fly, Sky Fighter. That was the very first book from the Asian Canadian community and that started the whole writing and publishing movement.

Zhen Liu: So you all took to writing from that point on?

Jim: Well that’s how we emerged. I think at that time we were just a bunch of people who were trying to support each other. I was going to an art school, doing photographs. I photographed from 1975 to 1981, six years of Chinatown. But for me, it was also a problem. At a certain point, I knew the community so well that there is so much more I wanted to say. So besides photographs, I had to write something about it. I wasn’t a writer and I only did grade ten. I really was quite insecure about that. I eventually ended up going back to university. I went into creative writing and I spent two or three years taking creative writing courses at UBC.

M ost pieces of Chinatown Ghost were from class exercises on the course. It was my learning how to write. It was good because I first needed to find a way to tell stories, because most of my poetry talks about stories, talks about people. It was to find a way to tell stories economically, but also with a lot of clarity. I am also influenced by Chinese poetry, you know, because it’s very simple verse, there are not a lot of words, but it has a lot of meaning. Anyway, that’s how we started, we wrote. And after we started writing, at the same time, we did an anthology because there was a grant available and there was a publisher that was interested.

ost pieces of Chinatown Ghost were from class exercises on the course. It was my learning how to write. It was good because I first needed to find a way to tell stories, because most of my poetry talks about stories, talks about people. It was to find a way to tell stories economically, but also with a lot of clarity. I am also influenced by Chinese poetry, you know, because it’s very simple verse, there are not a lot of words, but it has a lot of meaning. Anyway, that’s how we started, we wrote. And after we started writing, at the same time, we did an anthology because there was a grant available and there was a publisher that was interested.

Zhen Liu: Where was the grant from?

Jim: The grant was from Canada Council. At the same time there was a publisher who was interested, Douglas & McIntyre, which is a very good publisher. So my job was to find the writers. At that time, I thought there were only a handful of us that were writing. So I went down to UBC to the library. Those days the Main Library was like a dungeon, all six floors. I went there and looked through every magazine, every literary journal I can find for any Chinese names.

Zhen Liu: And that’s your method?

Jim: Yes, that’s how I found all these people. In fact, it’s quite interesting. There was Wayson Choy, one of those that I found. When I found him, I had to go and find where he is. And I located him in Toronto. And I said: “Wayson, do you have more stories?” He sent me two more stories. He had published three stories up to that point. And it turned out “The Jade Peony” was the only piece that was about his family and himself so that was the one we ended up publishing. That is how the anthology kind of evolved. We collected all the stories. It is unique because we also included some poems. We wanted to tell stories. Initially the anthology was going to include three elements. There was a lot of writing in Chinese before we started writing in English. There was already a whole corpus of literature before us. And I wanted to acknowledge it. So we took three or four of the best pieces and tried to translate them. But once we translated them into English, it didn’t work.

It’s because the forms are different: in Chinese writing they don’t have a form called “short story”. The contemporary term for this form in English is short story but they are called sanwen in Chinese, a vignette, it is not really a story and it didn’t fit.

When we translated them and put them together, they just look like bad writing. So I decided not to include that. But I did include some poems. Because we just wanted to include everything that we think that was good. We kind of put all the pieces together and hoped for the best. In any case, the book did very well. It was the first one of its kind. I think it was such a unique thing.

Zhen Liu: Yes! Also I think what’s most special about Many-Mouthed Bird is that you kind of located the emerging writers at a very early stage before they have completed their main work.

Jim: Yes, including some Chinese writing in juxtaposition.

Zhen Liu: Did you send out a call for papers?

Jim: No

Zhen Liu: So it’s all your personal efforts?

Jim: All this research. And all the people that I knew. I didn’t even know how to do a call for papers. That’s all we could find and we put them together. We put together what we thought what was the best. That’s where I learned the editing process. Because you have to piece something together so that they link up and it works together as one whole unit. I think that’s the saving grace because normally you either have a book of poetry or a book of fiction or prose. You don’t mix them. Ours was one of those that mixed them. And one critic actually took us to task for that. He said, though, normally it doesn’t work, but this one works well. So the first anthology became immediately required reading. A lot of universities and study programs began to use it.

Zhen Liu: At the compiling stage, did you have a framework in mind? For example, what kinds of categories with regard to either the works or the contributors that you were looking for?

Jim: No, first time you do something, there is no template. Nobody tells you how to do it. You just go out and do it.

Zhen Liu: I mean, did you look for first generation, second generation or third generation and new immigrants’ presence in the anthology?

Jim: No. We didn’t even consider that. You know, we were very young those days. I mean all this stuff came afterwards. At that point of time it was just to see what kind of writing was out there and what was in people’s minds and how that all interconnected with each other. I think that was the only criterion that was at work. There was a lot of karma, it all worked out. I mean, it could be nothing. We were setting out with the idea that we didn’t have enough. It was never the idea that we could successfully produce a book.

Zhen Liu: Is that to say that some of the contributors launched their careers with the publication of Many-Mouthed Birds?

Jim: Yes.

Zhen Liu: But some of them kind of disappeared…

Jim: Yes, some of them cannot continue producing . . . one of the best pieces in Many-Mouthed Birds was written by Anne Jew (“Everybody Talks Loudly in Chinatown”). I went to her first to see if she can reproduce the work in more depth and length for a book-length novel. She couldn’t. Wayson Choy was the second choice. And Wayson had only written that one story at that time. So he was forced to write all those other stories with a very short notice. We had a very good editor. She helped to put things together. It was a few weeks before the deadline for publishing that he finally got his last story.

Zhen Liu: Really? That’s wonderful.

Jim: Yeah, so he has never written. I mean, it’s amazing. If you think about it: the work is so mature and so powerful.

None of us has ever thought of having a career. A lot of us wrote because we had to. There are two kinds of writers: a writer that enjoys writing and is good at it. And there are people like us: we write because have something to say. The poetry collection The Chinatown Ghosts when it first came out was also used in a lot of schools because there were a lot of local schools that happen to have a big proportion of students of Chinese origin. But there was nothing for them to read about themselves. So the schools photocopied my book and used that for class. Therefore we knew there was a demand. Yes, the writers that emerged from Many-Mouthed Birds did very well and many careers were launched, because this gave them something to show to a publisher. That was the beginning.

What I did was, when they approached me to edit Many-Mouthed Birds, and after the book became quite popular. I was on tour at that time, you know, promoting the book in Toronto. I saw how successful the book was, everybody wanted to talk to us.

So I said to the publisher, you know, it’s kind of sad if some other publisher come by and scoop up some of these writers. Then when I got back to Vancouver, Douglas & McIntyre talked to me and said, “We would like you to continue help us to develop these writers for more publishing.” I said: “Okay, I have only one condition. Only if you gave me access to all your departments because I want to learn everything about publishing.” They agreed. I became the associate editor for Douglas & McIntyre for the purpose of just doing this. I walked into the publishing department and I basically learned everything about publishing.

Zhen Liu: How long does that take to learn all about publishing?

Jim: Maybe a year or two. I just went in there and talked to people. They told me this is what you do to market a book, and this is what you do to edit it, and so on. So I basically learned the whole publishing process.

Zhen Liu: But you do much more than this. Publishers do not approach new writers. But you discovered new talents and approached them to get them published.

Jim: Yes, but it was because we had already built up a reputation. We had a successful book. It became easier for us. I had to understand the process, because I needed to know what people wanted. I needed to know what a good, successful manuscript looks like.

Zhen Liu: Was that when ACWW was founded?

Jim: No, that is when we got to a point where I think we had to do something about it. Firstly, Paul Yee left for Toronto and SKY also went away. I think she went to Toronto or Montreal. So people were scattering. At that time I thought there were twenty or thirty writers. I probably know all of them. But I think there was one year, 1992 or 1993, some new people came looking for us. They were from the creative writing class in English department. They were graduating and they wanted to continue writing and they had nowhere to go. And in one year we doubled our number from 20 or 30 something to almost 70 people.

Zhen Liu: Who are they?

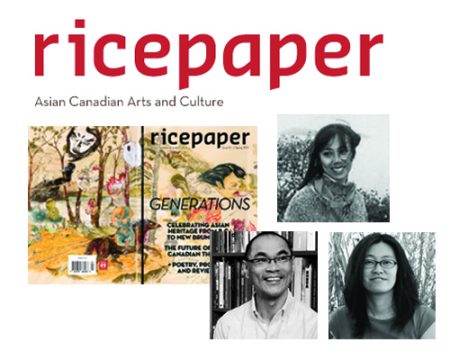

Jim: It was a new generation. A lot of younger writers. That was also the time when I finally met Denise Chong. The group started to organize itself. It also reached a point that the management needs to change. Before it was all easy, I can just call and tell people about publishing information. All of a sudden we have 70 people and needed some form of media to distribute information. That’s how we started to organize and developed a newsletter that we mailed to people. And from there we developed a society. The Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop began in 1995 as a society. Once the younger writers began to get published, we became their resource base. The newsletter happened for three years before the Canada Council gave us some money, and the next thing we know, we become a publication, and Ricepaper came out.

Zhen Liu: How did the ACWW start working with writers?

Jim: Jim Wong-Chu at a reading of Chinatown Ghosts at the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden in Vancouver, BC

It was very difficult, the magazines in those days, it was at such an early stage. We couldn’t produce enough work for a magazine. We didn’t have a lot of people writing out there. It took a long time. It’s only recently that we have steady flow of material. It was a learning process. We are not professionals. We are activists. We just somehow end up doing it. You learn everything from scratch. I think that’s also unique in what we were doing. Before 1990, there was almost no writing. However, in the last twenty years, we created a really comprehensive literature. So the work that began from ACWW, was based on the calling: “Why not? Why don’t we do this for ourselves?” We can’t wait for the writers. We didn’t have writers. We have to find the writers and get them published as quickly as possible. With the knowledge we can bring them to it. We started doing workshops. We found a lot of writers were at different levels. Some people were bored because it was maybe too elementary for them. It became very difficult to create workshops. We looked around and realized there were already very good creative writing courses in the community. So why were we competing? We then narrowed our scope. Our work became more about helping to prepare manuscripts. When you are developing manuscripts or when you are close to having a complete manuscript, we will help to prepare it to get it ready.

Zhen Liu: Do you have a set of criteria for manuscripts? What would you favour for “new” writings in terms of content and form?

Jim: The earliest writing was mostly about looking at the past. It just happens that way. The early writers were trying to get something out of their system. What bothered them most was about the family, about the past, about their identities, so that was in most of the earliest writing. The earliest writings are what I called confessional writing. Interestingly enough, it all came out at once. It’s amazing. All of a sudden, within a matter of five years, we established the canon of Chinese Canadian literature. The Jade Peony, Disappearing Moon Café and The Concubine’s Children all came out at the same time. Each one of these books won awards. It’s shocking! It was the earliest writing, which makes you wonder, “Why they are winning awards? Are they that good?”

Zhen Liu: Does it have something to do with the timing? The talk about multiculturalism in Canada?

Jim: Timing, the uniqueness, but also the fact that these writings are fairly mature, they are still standing against test of time. SKY Lee’s Disappearing Moon Café is the first novel, first contemporary Chinese North American novel. We were pioneering in those days and we are still moving things further ahead. We created an award called the “Emerging Writers Award.” One of the editors proposed it saying, at least in this way we can guarantee one writer come out each year. We managed to give two, one to Rita Wong for Monkey Puzzles and the other one to Madeleine Thien for Simple Recipes. The publishers loved them and both writers got very good promotions. Our award is unique in that most book awards are awarded after the books are published. Ours was designed to attract manuscripts. We also tried to get the runners-up published.

That’s why we are unique as we find the mechanism that works. We are actually going to re-launch the award this year.

Zhen Liu: That’s great news. And also making anthologies is a very efficient mechanism too.

Jim: We found that the anthology is a very unique thing. We did Many-Mouthed Birds because none of the writers had enough material to publish their own books. The anthology was a showcase. It was the simplest way to get acknowledgement and recognition in the publishing industry. That works also for Swallowing Clouds: there were not many poets who could publish their own collection of poetry, but after that there were a lot of those writers emerging.

And like Strike the Wok, I gave these anthologies names. That’s one of the things that I can do. I wanted a name that can bring attention to the anthology.

Zhen Liu: I am also interested in the cover designs. I like very much the one for Strike the Wok, but the one for Many-Mouthed Birds is criticised for having reproduced stereotypes of the Chinese in Canada.

Jim: It’s actually not. We have a guy who looks feminine. That’s the subtlety that we were looking for: you think you see something, but when you observe closer, you see something else. Anyway, I have no idea how the publisher came up with the image for the covers.

Zhen Liu: What about the selection process: did you have more concrete criteria this time for Strike the Wok?

Jim: You’d have to speak to Lien Chao about that. But she is very interested in including new immigrants or overseas writers. She is one herself. There were many very young writers that were part of that selection. I think it updates with the more recent stage of development of this writing. You see the different phases of the evolving of the literature with each of the anthology.

Zhen Liu: Since we are talking about a conscious process of making selections, I wonder if you are aware of certain preferences, or if you are trying to avoid having any so that certain voices don’t get appropriated.

Jim: The first thing that we wanted to do is to establish what is the best writing. The work itself has to stand out. Secondly, you have to look at the entirety and find the connections. Sometimes it’s not necessary that the best works make into an anthology. We look for links, so that one story connects with the ones [that] come before and after it. A reader reads to entertain herself. We don’t do, okay, here is early writing, here is middle writing . . . we don’t categorize that way.

Zhen Liu: But will some readers, for example, a new immigrant or a fifth generation, trying to find stories similar to their own, feel disappointed if they are not presented?

Jim: Well, that is not the purpose. It’s not to cater to certain reader groups. What I try to do is to map out what is best there and put together what is the best and most representative work at that time.

Zhen Liu: Is that to say literary values go before historical values?

Jim: No. When you are editor, you have the obligation to come up with the best works and also the most engaging and most representative works. Like it or not, it is entertainment. You read to entertain. Otherwise it will be difficult for you to continue reading. But the other thing is information. A lot times it’s very subtle, and sometimes something has to jump out at you. Sometimes it’s controversial and sometimes it’s not.

Zhen Liu: How do you find the connections then?

Jim: I lay them down on a table, and go: “Okay, we should start with this piece, and this should follow it.” You look at them and then you develop them. You develop a selection based on intuition and rhythm, you create a story line. For example, co-editor Bennett Lee said, Many-Mouthed Bird is a person who talks out of tune, about nuisances, and doesn’t know to shut-up. And that’s what we wanted, all these people squawking, saying different things in different ways. Therefore the concept works based on the ideal in the title.

Zhen Liu: I just observe that these four anthologies, they are twelve years apart from each other, and by that logic, there should be one this year.

Jim: I was actually thinking about it. I just don’t have time to do the work, that’s all. But I am thinking about it, just as we are talking I am thinking about it. You know we have published a lot in RicePaper, out of the nineteen years there has been a lot of good writing. So I am going to talk to the current editor, and see if she is interested. If she agrees to do the work, selecting the pieces and so on, I will approve it, give my comments and everything. If that can be done, we may produce another anthology in a couple of years.

Zhen Liu: Yes, I think it’s high time. . .

Jim: It’s also a time to look back at the writing. This one I want it to be pan-Asian. I want it to be much more inclusive. All these other ones are just Chinese, this next one I want it to be pan-Asian. There are some Thai, Filipino and Vietnamese writers.

Zhen Liu: It seems to me that you are in the middle of and behind everything.

Jim: Yes, I am the magician.

Zhen Liu: How do you define Asian Canadian literature: Is the fact that an author is Asian Canadian what counts or is the content of their writing more important?

The Asian Canadian Writers Workshop (ACWW) organized the LiterASIAN Festival in 2013 and it continues today.

Jim: A lot of people think that the Asian Canadian writer has to write about Asian Canadian things. That’s not true. The fact that you are Asian Canadian, and you are writing, already informs a certain point of view. You can be writing Science Fiction and you can be writing about a lot of things. The other thing is a lot of Asian Canadian writers hate the word Asian Canadian. They don’t want the hyphen, they just want to be Canadian. But in order to get us to that point where people are so used to it. Joy Kogawa is now known more as a Canadian writer. She managed to break through that hyphen, she is no longer known as just a Japanese writer. That’s what most writers aspire to and that’s what we are doing. The idea of ACWW is that at some point we become obsolete, there is no longer a point to us. We designed ourselves to become obsolete at some point. You have to have a mission. Once it is accomplished, it needs to transform and evolve, not stay the same. At this stage, we need to have new writers. We still need to identify the entire literature. You know, just because you have some good writers there, that’s not enough. We are still at the stage of building, but at some point, it matures.

At some point, the writers won’t be seen as Chinese or Japanese Canadian writers, as they become Canadian writers.

Zhen Liu: But how do you see those writings that do not contain Asian cultural elements?

Jim: There always are.

Zhen Liu: There always are?

Jim: The identity issue, and acculturation: there is such thing as Chinese Canadian, then there is Canadian Chinese and Canadian. But these categories are in your mind-set. These are different levels of assimilation of identity. Each one of these is valid. You have to acknowledge it and accept it. It’s like gender politics. You might agree or you might not agree, there are all sorts of versions. That’s fine. As long as that’s good writing, you can publish it and people are happy to buy your book. You know, when we are producing our books, we don’t think about how much we can make, we just want to get those books into the hands of as many as possible readers. We took that as our mission.

Zhen Liu: Will Ricepaper stay in print for the foreseeable future?

Jim: For the next little while, yes. But not for long. The funding is finally running out. It’s unfortunate. Nowadays it’s very hard for anything in print.

Zhen Liu: Do you see it your responsibility to lead the community?

Ricepaper Magazine, in print from 1996 to 2015

Jim: It was not just me. It was a group of very conscious people, activists that pushed this agenda. They are the pioneers that you see, Paul Yee, Denise Cheng, SKY Lee, Wayson Choy and so on. We are the first generation, we are the ones who responded to the duty and we are the ones that stand behind it. We are the ones who talk about it and encourage the newer generations.

The thing that is good is that we created a mould for the writers. Basically, we don’t ask them for anything in return.

We ask them to pay a membership fee, if they don’t pay us, it’s okay. All we ask is that they pay it back to somebody else. If someone younger come along they could spend the time with them and nurture them if they can, that’s all we ask. In that way we create the conditions for other things to change. They don’t have to, it’s okay if they turn around and say, hey, that’s me, I got myself rich and that’s it. That’s fine too. But most of the writers that come through ACWW, we ask them to give back. In that way, you create a spirit, and you create the conditions for dissemination. So that’s what we’ve done — we make everyone a missionary.

This interview took place in 2014 at Jim’s home. Since then, the ACWW has produced another anthology, Alliterasian: Twenty Years of Ricepaper Magazine, edited by Julia Lin , Allan Cho and Jim Wong-Chu. The ACWW has also organized the LiterASIAN: A Pacific Rim Asian Canadian Writers Festival. This is its 5th annual festival, happening September 21 to 24 in Vancouver’s historic Chinatown. The ACWW renamed its Emerging Writers Award as the Jim Wong-Chu Emerging Writers Award. Deadline for submission is July 1, 2017.