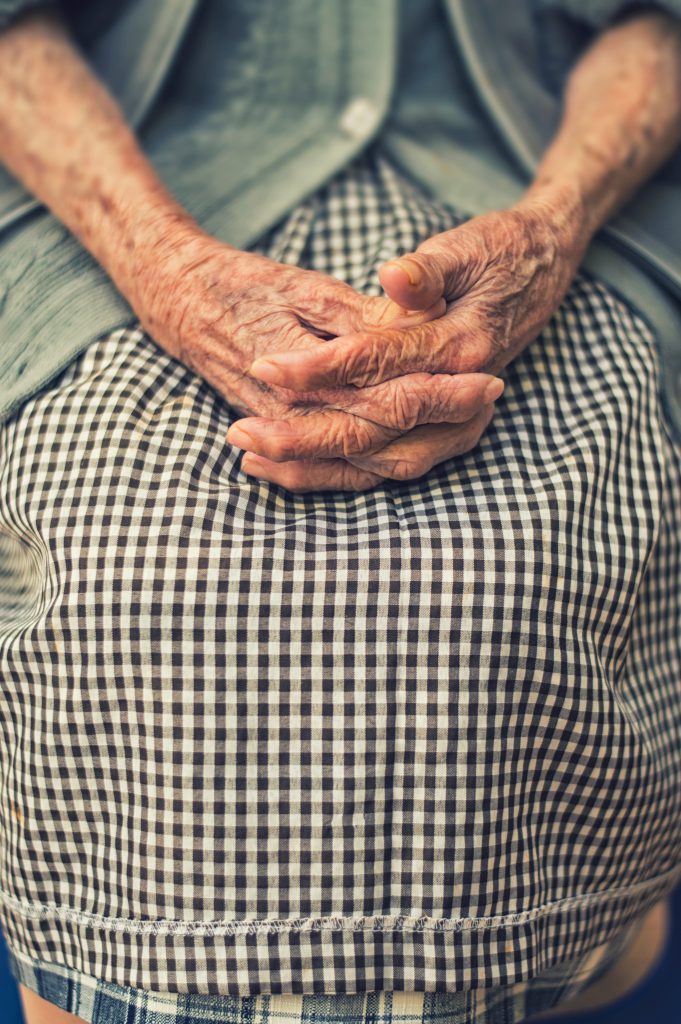

Photo by Cristian Newman

You told your grandmother that you would be away from home for three years. You would fly from the jungles of Borneo to Singapore for an overseas students’ orientation. Thence to Heathrow, London on BOAC’s student airfare with stopovers in Bangkok and Vienna. It was to be a long journey. It was 1969.

“You should’ve been born a boy,” Grandmother said.

“Wha…at? Why?” you asked.

Grandmother had been blind from the end of World War II and the Japanese Occupation in Southeast Asia. When you were little you asked to see what was behind her pale half-moon shaped eyelids. She seemed to you to be perpetually meditating, away somewhere in the universe while sitting upright on her hardback chair. Gently, you lifted each lid and saw only dull whites inside, not the abysmal wells you’d imagined blindness to be.

“It’s a man’s world, that’s why? You’ve seen how your mother has to deal with that.” Your grandmother spoke as if she could see. After a pause she said you were just as intrepid as your mother. Mother, a school teacher, had dared to rival established businessmen in town by bidding to be the wholesale agent of sporting goods. A woman dabbling in men’s business was an excuse for them to be delinquent on their credits. Someone even brought in a box of freshly made noodles from his shop as a payment that was thought would be more appreciated in a businesswoman’s kitchen. Your father remained a scholarly teacher of Chinese histories and the classics, and calligraphy writing in black ink on white scrolls.

At sixteen you asked your Aunt, “When did Grandmother go blind?”

“She had poor vision for many years before the war. Then one day, suddenly, after your grandfather passed away, she went totally dark.”

“But why?”

“Crying too often, she used to tell us. And depression. But we all suspected it was from your grandfather’s waywardness, you know, all those sluts!”

“My goodness!” you said under your breath.

As a child your aunt was terrified of her father. On his itinerant business of plying textiles and clothing and general goods, he’d spend nights in villages and towns up and down the river. Whenever he came home, he’d throw down piles of money on the dining table while cursing and swearing in his thick opium throat. Aunt and Grandmother would quickly gather up the bills and coins. Grandfather sometimes demanded some back; he’d miscalculated a gambling loan here or a drinking credit there. Both women would deny having a cent left after their household expenses.

“Wine, women and song, that did it, huh?” You had learned in your Anglican school to quote great sayings and proverbs uttered by some dead English and European authors.

Aunt said, “Our four active Chinese characters are sharper: whoring, gambling, drinking, opium smoking.”

For many years, Grandfather was siphoned off by a major bloodsucker called “The Siren.” He bought a little house for her family and dwelled with them most days. The minor sirens in more remote villages were paid off with satin dresses and cloths of rainbow colours, ribbons and curious knickknacks like buttons and zippers and embroidery threads. They were the pleasures of sail-by-night merchants while Grandfather was their ply-by-day and stay-by-night happy wayfarer.

Your father and mother? They took up teaching jobs out of town, often opting for towns as far away as possible. Your mother, especially, could not stomach the constant commotion and the neighbourhood gossip. Your grandmother would be crying and complaining, and Grandfather would be throwing temper tantrums befitting a thunder god.

World War II ended, the British governors returned from hiding or from Japanese imprisonments, and everyone else too, returned to live in town. The Siren had died, and your dissipated Grandfather came home. Grandmother was magnanimous to a fault as she obliged her prodigal husband’s dying wish: she was to meet The Bastard. Grandfather said that the boy could be another filial son to your grandmother since your aunt would one day have to live by another family’s manual of instructions on how a woman should behave.

Two days after coming home Grandfather asked for his favourite dish to be served to some friends who were to accompany him on a journey. Grandmother and Aunt made a savoury tea soup with ground tea leaves and ladled it into bowls of assorted cooked greens and herbs, rice, crushed peanuts, and sesame seeds. Grandfather supped with gusto and urged his invisible friends to not stand on ceremony.

Eat! Eat before the long road ahead! He died peacefully that night.

In later years Aunt found Grandmother’s blindness had sharpened her hearing. Everyone would run out to watch a cargo plane fly by long after Grandmother had said, “Here it comes again, that noisy giant insect!” Were Grandfather alive then, Grandmother would have had to suffer the amplified sound of him hacking out pieces of his lungs and liver.

Your aunt spent her teenage years spying on any teenager who came from the villages to shop or go to the big cinemas. She observed their mannerism for resemblance to your grandfather. Or even to herself. The more she looked the more she was appalled at the possibility, she’d said. Her whisperings and coded conversations with your mother or her girlfriends did not escape Grandmother. Grandmother could hear the kettle rallying to its boiling point. She had never boiled over anything, never overfilled her thermos flask. With that ‘play-by-ear’ skill, she could ‘see’ your aunt’s agitation. She sent a relative to fetch The Bastard. After a ceremony of tea and gifts, the boy was sent back to The Siren’s family. Your aunt was relieved from the fear of an incestuous date.

Still, your astute aunt made inquiries about the men she dated in her twenties. “One never knows what’s out there,” she said. In their correspondences she queried them about their relatives and ancestors, pretending she was interested in Chinese immigrants’ history in their British governed country.

“Can you imagine your aunt marrying one of your grandfather’s wild oats?”

Dreadful notion, indeed. But that your aunt might have more half-siblings out there meant that your grandfather had helped to populate the war-depleted planet with half uncles and half aunts of yours.

Your quotes itched and oozed out of you: “We are all brothers and sisters in this world…”

Your Aunt shot you a glare, a sharp ocular beam that could well laser your name out of her will. She would, too. You sometimes wondered why she was childless but never dared ask. But you shan’t digress. Ponder before you blurt, a virtue to have if you wished to remain the niece she most doted on. Her philately albums of postage stamps and First Day Covers and such items of letters written in Chinese calligraphy were reserved by your lesser cousins. You were to have far better hand-downs than those trifles.

At nineteen, you were emerging from babyhood feeling grown up, responsible, smart and looking forward to an eventful life and career in this curious world. Independence and enlightenment were such prospective words. You assumed everyone would accept you as their equal as everyone had always loved and admired you for your talents and diligence and had encouraged you to go for that further education. The American astronauts had just landed on the moon weeks before your flight to London. The world was going places and you were going with its vibrancy. You could have, unbeknownst to anyone, quaffed down a gallon of a beverage that was brewed by courage.

Naturally, what Grandmother said about your disadvantage of being a girl was a tad dismaying. But she was old, and blind. What did she know? You told her not to worry. You weren’t going to the moon, only 8000 miles away on the other side of the globe.

Her right hand cupping her cheek and left hand supporting her elbow, Grandmother mused that you’d be floating high up in one of those ugly insect planes she had vaguely seen during the war. Would they by some mistake fly you to the moon, too?

Oh, what nonsense.

“Heaven has a purpose for showering me with talents,” you quoted a Chinese saying from your Mother, adding for Grandmother’s sake, “though I be a girl!”

Grandmother nodded. “Hmm. In foreign places, not everyone would agree with you. There are jealous eyes everywhere. No one would care if you wasted your talents. But you sure are like your Mother!”

Mother once told you about the woman carer she employed during the month of your birth. The woman swore that had she been a mid-wife, she’d have refused to deliver baby girls. Fortunately for you, heaven had endowed her with a post-natal carer’s talent. The woman disliked your pee capacity, and you seemed to pee more often than other baby girls she’d helped to change diapers for. Besides, she was seeing too many baby girls being born in those post-war years. Well, you suggested to Mother, those two world wars could’ve discouraged boys from reincarnating for fear of being listed for future wars—you’d heard that argument in school or class debates or something. But Mother said the woman knew no other concerns than that you gave her too many extra diapers to wash. White and beautiful when washed and rinsed with a blue powder to make them whiter, the cloth diapers were line dried and sanitized under the tropical sun; back breaking work that was (before the disposable diaper inventor was born). Boys! So independent of diaper modesty it was delightful to watch them flash their wee pistols. Baby girls like you only leaked secretly…

“Pee on her!” you said to your Mother. “She’s a girl herself! She addled?”

The woman was tall and gawky and loud, your Mother recalled. She was conditioned to glorify all males as the pillars of the earth, the brains, the heads of tables and committees, the gods. The manual of instructions for her womanly behaviour would have included two important rules: Obedience to father at home, subordination to in-laws when married.

Years later, while tale-tattling to Mother you said that your mother-in-law reminded you of her gawky woman carer. Mother-in-law was loud and opinionated about having more diapers to wash for baby girls, especially when you dared to produce a second one.

Mother-in-law implored you not to stop production yet.

“Have another one,” she’d said, like she was asking you to have another rice dumpling or cake. Like the way she persuaded your friends at Chinese New Year parties to have another helping of her delicious spring rolls. She had made them with 95% pork fats and half-fat meat that she patiently minced on the chopping board and seasoned and laid on sheets of flimsy tofu skin. Wrapped up into eight-inch rolls and deep fried to a crisp, they were served in bite-size with a chili sauce.

Have another one! They were as irresistible as cute baby boys if you’d only try again.

“Be strong,” your Mother said.

You were shopping one day when you met a former classmate’s dad. He’d heard about your mother-in-law’s issue with you about another baby girl.

“At least I issued a healthy baby, not a cockroach,” you said. “Wouldn’t it be fun to see mother-in-law cuddling a grand-roach?”

After a good cackling your friend’s dad said he’d heard that your mother-in-law prayed to her dead husband and his ancestors to bless her with a grandson. In that sleepy town, if one were to fart in a tightly secured closet, people would wake up instantly and talk about the colours of that fart. Everyone’s nose was in everyone else’s business, your Mother used to say.

“Now, tell your mother-in-law, a woman is sitting on the English throne that once sat her father. Ha! Isn’t that something enough? And a woman prime minister is governing India, right now! Margaret Thatcher is climbing like a man up the ladder of politics! She’s no housewife!”

Fist bumps. “Congratulations,” he added, as if your daughters were destined for world positions, too. His own family, harking all the way back to his remotest great ancestors, had only boys born to them. He and his wife had prayed hard but failed four times to produce that rare gem of a daughter, that which would have been an earth-shattering event for his clan.

You said it was a little too late in the day but that they would’ve done better had they prayed instead to your mother-in-law’s mighty gods and ancestors.

Grandmother marveled that you were going to study in a foreign country where people spoke only English. Would you forget how to speak Chinese after three years? Grandmother had a broken dream of being an independent woman with a teaching career like your Mother. Married off at a tender age to be first a good daughter-in-law and then a wife, Grandmother at age twenty had to sail from Guangzhou to Borneo to join your Grandfather. Grandmother said she was once worried about your Aunt’s misfortune in marriage, what with her outspokenness. Your Aunt, a meek daughter-in-law? No way would she let anyone determine her fate. Her husband was a docile live-in son-in-law to Grandmother. Aunt was not about to let The Bastard back into their house, ever.

When you and your family were leaving for a new life in Canada, your Grandmother was too deep in a coma to know about your uprooting and relocating to farther than 8000 miles away. She was already embarking on her own journey back to the universe, her passage mapped out, perhaps with a layover on the moon.

But before that, what did your Grandmother say about you having two girls?

You recalled the moment when you told Grandmother about your mother-in-law yelling at the gods and ancestors’ name tablets on the altar. They had failed her after feasting grandly on their anniversaries and festive occasions. Giant spring rolls with 95% pork fats fried to a crisp. Chicken marinated in soy sauce and five-spices. Roasted duck. Suckling pork delivered by a reputable restaurant. Heaped bowls of snowy white rice. Mini cups of whiskey. Bundles of expensive red candles and paper money were burned.

Grandmother chuckled. “She should’ve offered up that feast of vegetables and tea soup I served your grandfather and his spirit allies! Did your mother-in-law actually believe those dead ancestors supped on her offerings?” She gestured with a hand to waft the aroma of the banquet to her nose and pretended to sniff and close her eyes in appreciation.

Your mother-in-law chided herself for failing to follow the good old tradition of checking the horoscopes of her son’s bride-to-be. Tragically, owing to your shortcoming, your husband’s paternal branch, like a cosmetic line, was discontinued.

“Stay strong,” was all your mother had to say to that.

Your aunt had a stipulation about dating when you were in college. One should ask about their family relationships and relatives—blood tests and family members’ mental and physical health. Never mind their real estates, yachts, or oil wells.

In her days she could only pry and depend on the boys’ honesty and sincerity.

You were digressing again, but you could never forget how your gracious aunt was disappointed that you did not thoroughly research your husband’s family before uttering that fateful “I do.” You were negligent, she’d said, shaking her head. Consequently, you married a mother-in-law.

“Now she’s threatening you with a concubine for her son! Hint! Hint!” Aunt’s voice was no less stentorian than that of a thunder god.

But what did Grandmother say about your refusing to “have another one” of your mother-in-law’s spring rolls?

You remembered now. Your octogenarian grandmother said, “Another girl, huh? Good! About time! Have more baby girls! The more the better!” You thought you saw a glint in her bat blind eyes. She closed them permanently six months after you were settled in Canada.

One summer, mother-in-law came to visit her son and his family in Calgary. She had disposed of her altar table, she said. She was only too happy to live with her daughter and son-in-law in her golden years of leisure and mah-jong sessions. She confessed to you that she had fought tooth and nail against her father-in-law and mother-in-law who had wanted her to give up her baby daughter for adoption so she could concentrate on producing boys. She felt heaven had rewarded her in her old age for disobeying the silly elders. She also said that you were more fortunate to have two girls.

What would Grandmother have said about that sea change, you wondered.

Alice Y. Yong emigrated to Canada in 1981 with her young family from Sarawak, E. Malaysia. Her Southeast Asian-Chinese cultural background and English education informed her taste for diverse life topics and character studies in literature. Her two non-fiction books (Oxford University Press 1995/1998 under married name Ho) are researched works on Southeast Asian cultural histories. She has a BA degree in English Literature from Queen’s University in 2007 as a matured student. After years of globetrotting, photography and art appreciation, Alice is currently working on long and short fictions based on her sojourns in Asia, England, and Canada.

2 comments

A very engaging short story, beautifully capturing the tension that can exist between maternal generations. I would consider changing the “you” pronoun to “I” to make it more personal — a journal entry for the reader to take in as a glimpse into the life of a woman of Asian decent in the latter half of the 20th century among her older family matriarchs. Well done Alice.

Congratulations Alice . I very much enjoyed reading.

Jane Wickham