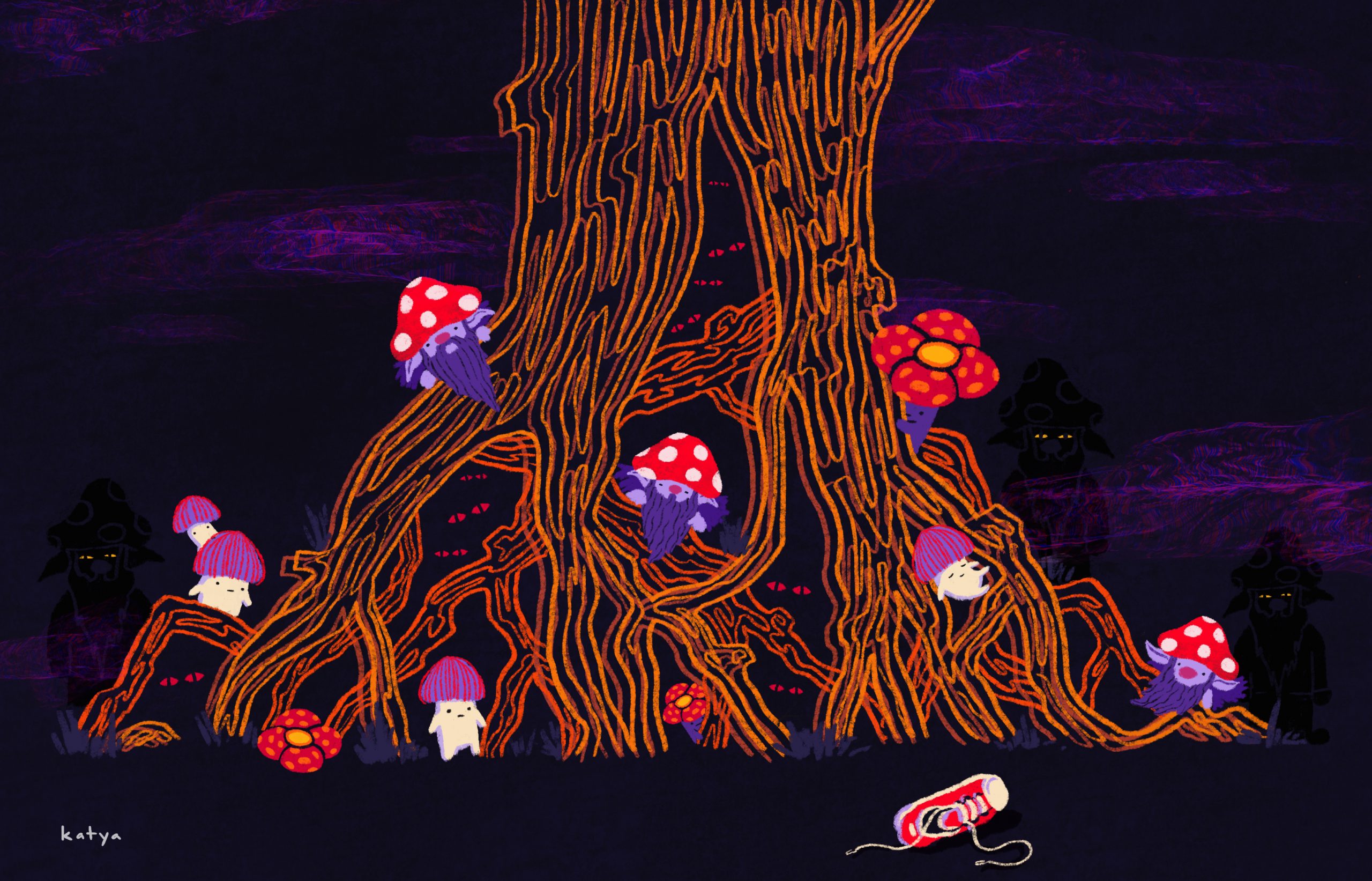

Illustration by Katya Roxas

The stone remained cold and silky gray in the boy’s palm.

He was in the middle of a procedure that many in the village had seen performed and found nothing spectacular about. Yet he sat on the bamboo steps of the hut in rapture, eyes bright with the idea that at any time a sort of magic was to take place, and his palm, with the cold gray stone, would be the central point of its demonstration.

Set on experiencing the unnatural, he absent-mindedly used his free arm to lock his older cousin’s elbow into an anchor with his own. The older cousin, a girl, was herself amused at what was unfolding: here was an eager, clueless child by her side; an elderly healer in front of them, murmuring what might be a prayer in earnest, and their aunties, fidgeting and fanning themselves to fend off the heat. It was only the sun at midday, but this mild deviation from their normal worked quite a discomfort on the two women. They kept their worried eyes on the boy – he who, the night prior, told his older cousin about his unusual little men friends.

–

“There were two types,” he said, the evening having barely touched the tiny space that made up their entire kitchen. “The first one,” he commenced, “only wanted to play under the stairs” – their old rickety stairs at the house he grew up in in the Visayas – “favoring small toys, especially colorful marbles.”

“The second, sinister type,” he added, waving his finger, “would, after a game, offer you food in the wrong color, like rice in black or water in a dark blue.” It was this second type that constantly urged you to go home with them.

His older cousin, who was tinkering with the stove handle, paused before interjecting: “You mean you were playmates with a duwende on several occasions?” The boy confirmed this but clarified that it was not just a duwende but a handful of them, never mind that they showed up erratically, with varying energy, and dressed so alike it was possible he had counted one many times over.

As for the rules: never gloat when, in your games, you find yourself on a winning streak (the little men disliked having their friendly losses rubbed in), refuse all food politely, and decline every invitation to accompany them home. If you gave in, well, you were never sure you could return – that much he knew. So be stern in your refusal. And if they keep pressing this point, it wouldn’t be wrong to threaten them with ending the friendship altogether.

But, the boy went on, the last he saw of these friends was in the driest of summers, before he was taken here up north to where their aunts lived, on that excruciatingly long trip by bus “for a vacation,” as he was told then.

He remembers, though, and this he relayed to his cousin evenly, barely hinting at how he felt, that his mother, who worked in a teaching assistant post in the Middle East, was set to return around this time of year to their own home in the province – so why was he here, so far from where his mother would have wanted him to be?

Oil crackled violently as his older cousin placed a slab of tilapia into the skillet.

She couldn’t tell him what she and the aunties already knew: that his mother had stopped communicating with the family. A few weeks back, they received word that she had given birth abroad, to a chinky-eyed multiracial bundle – if the stories were true, and how quaint that they relied mostly on rumors still.

It had been over eighteen months since she left the country. “For my son,” she said back then, adding that perhaps, with some luck, she’d be able to send for him so the two of them could start over, eventually, as Canadians or Australians or whatever the appellation for wherever would be the most suitable place to move to later on. Husbandless and so very young, no one at that time doubted her grit – no one wanted to – until she grew elusive online and stopped sending funds for the boy’s upkeep.

“Can’t I say it out loud?” one of the aunties said as the other shook her head and sunk her chin in defeat. “The girl’s a disgraciada through and through.”

There it was then, judgment pronounced – after holding back on labelling her for years. The aunties declared too that there was no use arguing their kin’s fitness for motherhood. The clueless child, who crossed the San Bernardino Strait on board a ferry, assaulted by sea and wind, and who after that, traversed several towns of the Bicol region by bus before reaching the aunts in Southern Tagalog, had for them been rendered necessarily motherless; this compounded by the fact that his father up to this day remained unknown and unnamed. By default then, the childless aunties in the family could claim him as their own.

When he arrived, unkempt and needlessly shy, they looked at him as much with love as with pity, with a nervous expectation that he would approve of them too. They wound their arms around the boy, as if to tell him they would protect and nurture him from there on in.

The boy smiled and smiled as the women fussed and gleamed, trying his utmost not to appear worn down. But later in his sleep there would be the sea spray, blotting the window of the ferry’s air-conditioned inner deck as his tiny body retched and tumbled from seasickness.

At dinner, the older cousin told the aunts the boy’s story about his so-called little men friends.

Now, these elderly women were clear-headed even in a crisis. They had heard of these stories from their hometown, of duwende befriending – sometimes abducting – children. And though the aunties were modern city dwellers now, they never quite developed a conceit against traditional healing, which they thought of as the first line of defense in these situations. Hence, the following day, all four of them set out for the western coast. From there, they took a banca to the healer’s village across the bay.

And that was how the motherless boy, friend to little creatures and believer in magic, ended up ensconced in the healer’s humble residence.

There were other children milling about the hut too, and rarely with a complete set of clothing. It seemed they preferred to walk around without slippers – liked, perhaps, how sand felt on bare, tiny feet. They were as raucous as the little boy was solemn, and very easily given to laughter.

As the procedure in the boy’s palm progressed, with the healer’s murmurs turning into audible syllables, mothers came one by one to pick the children up, whisking them home for lunch and scolding them for carousing, telling them off for discarding their clothes and slippers. The sun was too high up, they said. Not the time to be out and about and careless.

By this time, the healer had plucked the stone from the boy’s palm. With a mallet, she crushed the pebble into fine powder. She then took out a thin, pliable metal like a razorblade, used it to make a swift, shallow cut just under the boy’s thumb, and slid some powder into the bloodless sliver of skin, as neatly as one would a handkerchief into a pocket.

The idea was to have the consecrated particles act as a talisman against the supernatural. “Don’t worry too much now,” the healer entreated. The boy, she said, will be safe from seeing and being seen by those who aren’t like us – the ones the aunts referred to as “mga ginlabog han gino-o,” creatures whom God threw away.

The older cousin, meanwhile, assured herself that the cut was, thankfully, too superficial to risk infection. And despite her doubts, she sincerely hoped this would work. She had lived with the aunties long enough to understand how they willingly teetered between past and present, and how their pragmatism was such that if the boy later on claimed that he could still see his little friends, the women were just as likely to see another spiritualist as they would a psychologist, if they could afford it.

Before he came to see the aunts, the boy thought, mornings meant rising to an adlaw, not a sun, and on warm nights he would run around in his slippers playing tag with other children under a bulan – prior to calling it the moon.

When this, his adoptive tongue, was introduced to him – to prepare for his new school, the aunts said, where students are asked to speak only English – he had already learned at home the languages of the Pacific gods, the way his mother did. The aunts sometimes spoke in the vernacular too, but not as easily as his mom.

Another memory: of mosquito nets and petrol lamps, his mother, graceful and kind, whisking the air rhythmically with a woven fan, keeping him cool as they lay on a sleeping mat one humid evening. She liked to sing to him a – “Here before we head back,” he heard the younger auntie call out as the banca came to a halt and he was jolted to the here and now.

They were taking a different route back, so this stop was a curiosity for the boy. The older women disappeared into a row of wooden structures baking neatly under the sun, perhaps on some errand he had failed to catch as he daydreamed.

“Lemery,” his cousin volunteered. They saw that this town did not have the yellowish sand of other beaches. Rather, sediments of black ran the length of the shore. Now and again, waves bathed the sand in seawater, leaving behind a rich black pudding. Only in parts not reached by the water was the sand loose and an uneven gray.

His cousin told him that there really were no white sand beaches in this part of the country. The beaches in nearby areas, so advertised for their near-whiteness, merely had layers of light-colored sand gouged from elsewhere, possibly the islands to the south, which were poured over Batangas’s black shores.

They were standing on authentic, unprettified sand then; a welcome and unassuming contrast to the water that in the distance spread into the silvery blue sea. The boy tried removing his slippers, but at half past two in the afternoon, with the sun well above the horizon, he found soon enough that the sand was too hot to walk on barefoot.

Why haven’t the aunties returned, the older cousin wondered. And, out loud, “Probably saw something they liked and are still haggling with a vendor now.”

At this, a query lingered on the boy’s face. “Do you think this,” he held out his palm, “will still work when I get home?”

She paused to consider what the question implied. “You mean you still want to see the little men?”

“With the aunties, well, I have to be polite. But I never wanted my friends gone.”

She understood now how all throughout no one had asked this hopeful, confident child.

What she would like to do was return to the banca and sit on one of the wooden outriggers. She would dip both feet into the water, slice the surface with her ankles, and watch the water foaming in swathes.

The boy, on the other hand, stared out, content, mesmerized by the vast horizon; he was thinking what it would be like to ride on the back of a cloud.

Rachel Abelinde is a Filipina lawyer based in Manila.

Katya Roxas is a Communications and design specialist. Her portfolio is at https://www.heyakatya.com/

1 comment

The story achieves in depicting a real moment that happens in the Filipino provincial setting, written beautifully to simply show the circumstances of a boy and the people around him, but profound enough to make you feel for the character. At the same time it was able to present Filipino folklore in a creative and unique way, that has not yet been done by other writers.