After ten years of intensive research and interviewing elderly survivors, academics, lawyers, and activists in different nations, Sylvia Yu Friedman is a global expert on “comfort women” military sex slavery. As an award-winning filmmaker, investigative journalist, speaker, and writer, Sylvia is the author of three books, Silenced No More: Voices of Comfort Women, the only journalistic account of historical Japanese military sex slavery during WWII, and Heart and Soul: The Life Story of Pastor Augustus Chao. A Long Road to Justice: Stories From the Frontlines in Asia is her latest book. We caught up with Sylvia for an interview about her work as a writer and a journalist.

A Long Road to Justice: Stories from the Frontlines in Asia describes your journey of interviewing survivors of sex trafficking then and now across Asia as a journalist and advisor to ultra-high net worth family offices of billionaires and filmmakers. One of your book’s core messages slavery is not a historical issue – it’s still happening today. Why is history repeating itself?

A Long Road to Justice: Stories from the Frontlines in Asia describes your journey of interviewing survivors of sex trafficking then and now across Asia as a journalist and advisor to ultra-high net worth family offices of billionaires and filmmakers. One of your book’s core messages slavery is not a historical issue – it’s still happening today. Why is history repeating itself?

Great question. The repeating cycle of sex slavery is a vital message that the world needs to know and one that I’m sharing in a feature film that we’re producing based on my memoir, A Long Road to Justice.

I have had the incredible privilege of interviewing several elderly survivors of Japanese wartime sex slavery in different countries before they passed on. These extraordinarily brave women urged me to tell the world about their experiences and of how they endured the unspeakable. Investing time to meet these women and raising awareness for the next generation is something that I’ll never regret in life even though it took around 14 years to finish my previous book, Silenced No More: Voices of Comfort Women, due to the challenges and obstacles of language barriers, travel, schedules, and more.

In A Long Road to Justice I described the personal back story of this long journey – which I see as a form of public service – of documenting and bearing witness to the horrific abuse and war crimes committed against 200,000 to 400,000 girls and women across Asia Pacific by the Imperial Japanese military before and during WWII. It was largely because I had interviewed and been exposed to the experiences of these courageous elderly wartime sex slavery survivors that I was able to discern the awful parallels in the sex trafficking of girls and women today and the cycle that was repeating.

I remember sitting with a survivor of bride trafficking in southern China named Mei. At 14, she was sold to an elderly farmer and he chained her up like an animal in the house and unchained her whenever he wanted to use her. She told me of how she was lured with a promise of a shopping trip by a friend’s “auntie” but was instead dropped off at an apartment, locked in a room, and starved for 2 weeks. She was beaten into submission before a farmer came to inspect her like cattle and buy his new bride

As she told me the details, I literally saw the faces of the elderly women survivors like Kim Soon-duk who was a teenager when she was lied to and told she would have a job and then was taken to China and violently beaten into submission to receive up to 40 to 50 Japanese soldiers a day.

I do believe that if the Japanese government had been held accountable for the war crimes of sexual violence during armed conflict – for sanctioning and enslaving hundreds of thousands of girls and women in their military sex slavery system, it would have brought much-needed closure, healing to the survivors and to the people groups affected by the war. It would have sent a profoundly important message of “never again” shall girls and women suffer from sexual violence and rape during war and this would have had a deterrent effect on modern-day sex trafficking.

Resolving this war atrocity would have also enabled Japan to unite with Korea and China to eliminate modern-day forced prostitution; however, since they are unable to agree on historical military sex slavery, they are unable to work on stopping the cross-border trafficking of people.

Women and girls today from impoverished families are still tricked and deceived into forced prostitution with false promises of a good job just like the women and girls forced into prostitution for the Japanese military. Racism marked the historical wartime sexual servitude system and the price of tickets for darker-skinned women was cheaper compared to the ones for fairer-skinned Asian and Dutch women. The Japanese felt they were superior to the Chinese, Koreans, and other people groups. Today, racism still fuels sex slavery. A survivor told me that the Vietnamese trafficked girls and women in China were beaten more severely than the Han Chinese due to their perception that the Vietnamese girls were inferior.

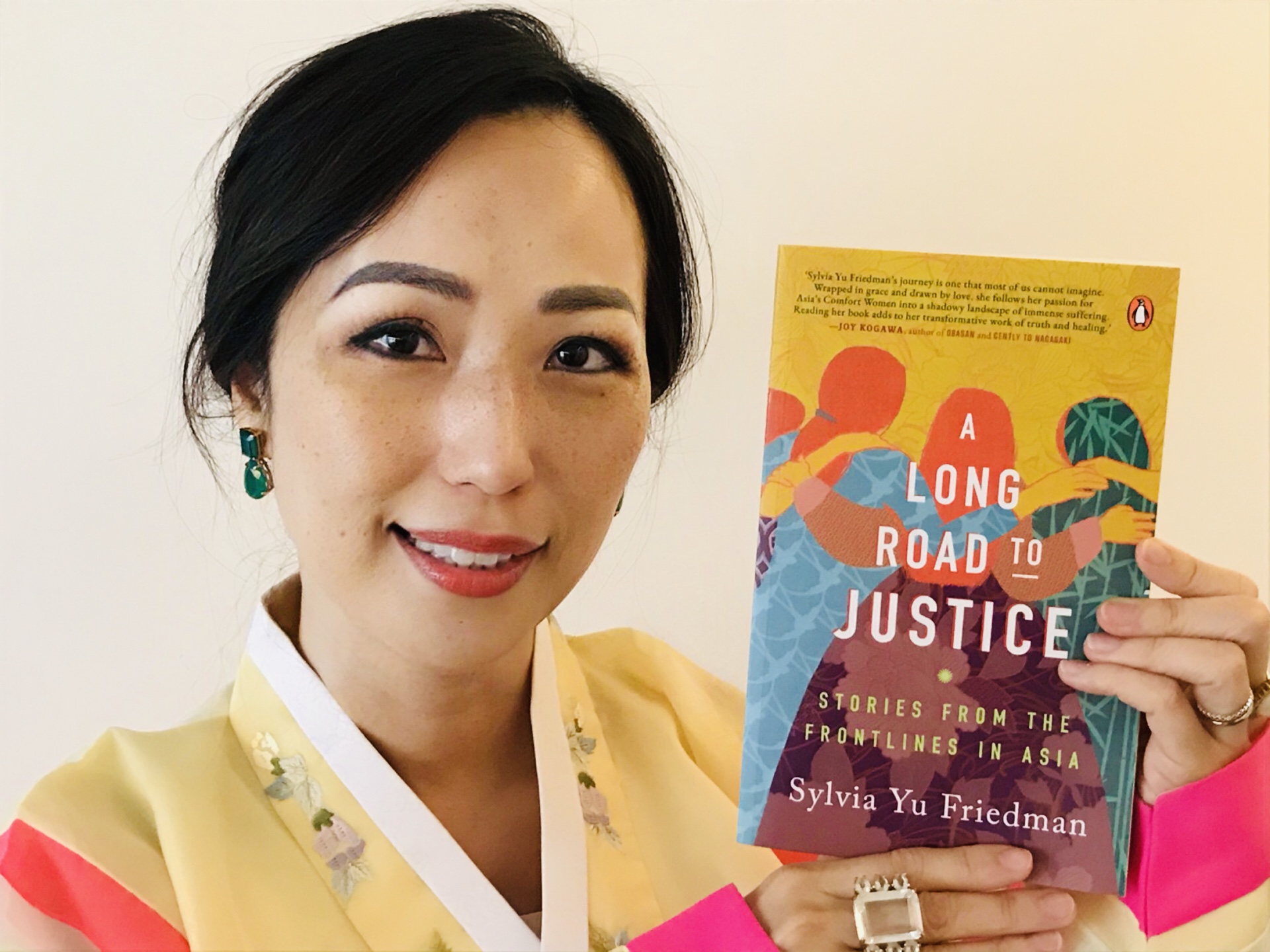

Sylvia Yu Friedman with her latest book

Your book is also a memoir, and you write about your identity issues as a Korean-Canadian woman in Asia. You had written under a different name at one point as well. How has your identity evolved over the years in your journeys and work in Asia?

The entry point for me into my social justice work and writing was experiencing the painful humiliation of racial discrimination. I grew up in an all Caucasian neighbourhood and elementary school in South Burnaby in the 1980s and I didn’t see one single Asian role model in the media or in any position of authority in school etc. That had a profound effect on me and as a result, I felt a sense of shame surrounding my Korean heritage and I longed to look like my Caucasian peers. I decided at a young age that I would never speak Korean with my parents and asked that they call me by my English name Sylvia instead of my Korean name, Saejung. That’s why it was important for me to write about the history I wasn’t taught in a school of girls and women in Asia forced into wartime prostitution by the Japanese military during WWII.

It was over the last decade that I began to explore this pain surrounding the self-rejection of my Korean identity, of what I looked like; and even my womanhood since I was rejected for being a girl by my grandfather which led to subconscious striving for acceptance from my father and grandfather. I also began to delve into generational racial hatred towards the Japanese that I’ve seen in many Koreans and Chinese from the unhealed wounds of WWII that has resulted from a lack of a truly sincere healing apology from the Japanese government to all victims of war crimes such as the military sex slavery system and forced labour victims etc. It led me to conclude that we need racial healing and conciliation in East Asia.

At one point, when I first published my book, Silenced No More: Voices of Comfort Women, I wrote under a pen name to protect myself from ultranationalists in Japan. To my surprise, when I spoke about this book and showed my documentary Healing River about a Japanese reconciliation team that apologized to elderly survivors of wartime forced prostitution in China, at least 4 to 5 people in the audience would be crying after the film. I’ve heard from people – too many to count – in Asia say to me that they didn’t know there were good Japanese people. At these events, I would almost always have a quiet moment of silence and encourage everyone to release forgiveness towards the Japanese. I never expected to have a racial healing element to these talks or be part of a ‘forgive the Japanese’ campaign but I’m very grateful to see this.

A huge turning point for me is that I have come to embrace my Korean heritage over the last several years and to my astonishment, many doors in South Korea have opened up in the entertainment industry for my feature film and my latest book.

Speaking at a conference at an anti-trafficking conference in 2016 in Hong Kong

You had led a Hong Kong-based movement of passionate compassion against human trafficking that involved more than 120 churches, NGOs, and organizations. There’s a part of this book that touches on human trafficking in Hong Kong-based on your work in the city. With the city transforming before our eyes, does it affect your work? What will you focus on next?

I plan to travel more to South Korea and other countries for work in the coming years. But I’ll always have a home base in Hong Kong and this international city has a special place in my heart. I met my husband Matt Friedman in this city. I have been able to launch internationally from here two books, films, the anti-trafficking campaign called the 852 Freedom campaign, and my husband’s books and anti-trafficking projects.

While the staggering wealth gap in this city is tragic; however, Hong Kong people are some of the most generous on earth. For the rest of my life, I plan to always direct philanthropic giving to the most marginalized people and places whenever I can. I’ll never forget the day I met the 83-year-old wartime sex slavery survivor Kim Soon-duk in Washington, DC. She flew all the way from Korea to call on the US government to pass a bill that encouraged the government of Japan to apologize for forcing between 200,000 to 400,000 girls and women into military sex slavery. I call it the day my life changed forever.

Now I’ll work on producing a feature film based on my book to educate more people about this chapter of history about Japanese wartime sex slavery in the hopes it can be a generational change tool and to inspire racial healing in East Asia. I also have three other books that I’m writing including a novel based on three generations of Korean women.

You’ve done a lot of work in the regions in and around Southwest China. In Myanmar, you once interviewed a 19-year-old named “Ma” who was HIV positive and slept on a tattered mattress in the forest every night. He had left such an impression on you. Could you share with us his story?

You’ve done a lot of work in the regions in and around Southwest China. In Myanmar, you once interviewed a 19-year-old named “Ma” who was HIV positive and slept on a tattered mattress in the forest every night. He had left such an impression on you. Could you share with us his story?

I was affected by Ma because of his young age and he was dangerously on the edge hovering between life and death. I was saddened that he had lost control and passed out in the field – his permanent home. He had no one looking after him other than my friend Bangyuan, the frontline worker in Kunming. I was on this donor trip on behalf of a billionaire family and I had to report back on the measurable impact of the funding to several NGOs that were working on HIV prevention initiatives and these often included outreach to heroin addicts who were vulnerable to contracting HIV from needle use.

We didn’t have a lot of details about Ma’s family or what kind of life he led before his drug addiction. But to witness his descent into darkness even for a brief time was beyond tragic and unlike anything I’ve seen because he was in the prime of his life at 19.

In order to cope with these terrible stories and let off some steam, some of us went out to karaoke that week and sang our hearts out to cheesy 80s song videos in a border town close to Myanmar. But working with these addicts was Bangyuan’s work day in and day out through the non-profit organization he worked for. My Canadian friend Dorothy was with me on one of these trips (she was at karaoke) and she said it was life-altering to see such extremes and desperation in a diverse province like Yunnan which I describe as being like the wild wild west of China.

The other people, especially the underage victims of sex trafficking I met during this period in my life left a mark on me and was very sobering. It helped to put things in perspective and that is what I had stressed about before: a challenging day at work, difficulty communicating in Mandarin, etc were insignificant compared to what the vulnerable and exploited face.

I am surprised by and extremely thankful for the many crazy adventures I’ve been on in China and across Asia and several of them were quite perilous, more than I realized at the time. I’ve been on the underground railroad in Asia where smugglers help rescue North Korean refugees, I’ve been confronted by vicious mamasans and gangsters in red light areas while filming sex trafficking victims, I’ve had to walk by armed soldiers at a border area while crossing back without a passport, I’ve driven in remote areas by the Myanmar border where the roads are dangerously thin, I’ve taken photos in one of Myanmar’s red-light districts where gangsters were watching and lived to tell about it.

Your journalism doesn’t limit the term slavery to just women. Your film “Slave husbands” was a phenomenon you had exposed for the first time in 2013 for a TV documentary, then in a news article in 2017. Could you share with us how you first encountered this issue and why did you want to document it?

I have always felt that my role as a writer was to give a voice to the voiceless. The exploitation and enslavement of men is something that’s been overlooked globally for a long time and programs to help them are not well funded at all. Women and children in slavery get the bulk of the attention and rightly so. But we must also care for and support men suffering in slavery.

I was shocked by the stories of more than 20 South Asian men who were from impoverished families. They were all married to South Asian women born in Hong Kong to families that had lived in the city for generations. Usually, the brother of the wife or father did the abusing of the “Slave groom” and controlled his movements by taking away his passport and bank cards and more to keep him absolutely dependent. The slave husband victim had no access to his own money and worked as an indentured servant for his wife and her family. Most of these victims had an expectation that they would be able to send money back home to their parents and it would have been a lifeline to them. Due to crippling shame, these men could not bring themselves to speak out and ask for help or when they did go to the police, things were twisted by the wife and her family and the blame pinned on the male victim.

I wanted to put a spotlight on it because there were several victims and it was a new type of exploitation and I hoped it would raise important awareness to help stop it. I had two reactions to the story: some South Asian professional men reached out to thank me. There were also some irrational community leaders who accused me of false reporting and disparaging their people. It’s unfortunate that sometimes the most barriers to raising awareness and eliminating exploitation come from within the community.

I have also investigated and exposed Bangladeshi men in crippling debt bondage to exploitative job agents. In Asia, it’s the men who are the breadwinners and when they are enslaved and not paid for their labour, their wives and children back at home suffer too.

I want to return to your earlier book about the life of Reverend Augustus Chao. It’s a fascinating story of a Hong Kong banker who came to Canada, temporarily leaving behind his wife and five children, to attend classes at the Canadian Bible College, founding Chinese Alliance churches in Canada and Australia and in parts of America. Eventually, Rev. Chao accepted the call and arrived in Vancouver with his family in June 1966, and led the Vancouver Chinese Alliance Church. How did you come across his story? How has your own faith influenced the work you’ve done and continue to do?

I want to return to your earlier book about the life of Reverend Augustus Chao. It’s a fascinating story of a Hong Kong banker who came to Canada, temporarily leaving behind his wife and five children, to attend classes at the Canadian Bible College, founding Chinese Alliance churches in Canada and Australia and in parts of America. Eventually, Rev. Chao accepted the call and arrived in Vancouver with his family in June 1966, and led the Vancouver Chinese Alliance Church. How did you come across his story? How has your own faith influenced the work you’ve done and continue to do?

I wrote an article about the incredible growth of Tenth church under Pastor Ken Shigematsu’s (older brother of playwright, actor, broadcaster Tetsuro Shigematsu) leadership for a magazine, and then a month later, a friend of Reverend Augustus Chao contacted me and asked me to write Chao’s biography. I said yes immediately and was drawn to his project. I was particularly excited to help document an important and rather untold part of the Chinese community’s history in Vancouver – its church history.

Churches in the Chinese and Korean immigrant communities have functioned like community centres or social networking hubs yet these stories have been largely undocumented.

Augustus Chao was indeed a fascinating person and leader in the Chinese community in Canada. He was single-minded when he decided to do something. He was considered the father of all Chinese churches in Vancouver in the latter half of his life. He was an HSBC banker in Shanghai and felt the call from God to pick up and leave for Hong Kong, leaving his wife and children behind. They would later follow him to Hong Kong, then to Vancouver. He faced challenges in his pioneering work of establishing churches just for the Chinese in Canada, and faced some pushback and at times, racist attitudes. At first, he didn’t want to write his biography and our first five meetings or so were very awkward and one-sided: I did all the talking. But I was persistent and we formed a very beautiful friendship. He became a grandfather figure to me.

When I moved to Beijing in 2004, he came to the airport to say goodbye to my family even though his health was quite frail. I had a heavy heart in leaving him behind. Right before his death in the hospital, I happened to visit Vancouver at that time and went to see him. It turned out that he had waited to see me before passing to the other side. I learned valuable lessons from him about perseverance, how to handle people’s politics (don’t care about what others think), and overcoming obstacles with faith and joy.

His pioneering spirit inspired me greatly and his example helped to deepen my faith which has become central to my life and motivates me to walk in love, peace, forgiveness, and compassion.

Sylvia Yu Friedman filming in Poipet Cambodia. This trip was mere several weeks prior to the China filming trip where she had a near-death experience in 2013

You had written this book during the pandemic and many things happened during this time. Your husband, Matthew, had also published a book during this time. How has the pandemic changed the way you’re writing, your filmmaking, the way you’re looking at the world now?

My husband Matt Friedman overcame cancer in 2018 and it was an extremely traumatic experience and also a rebirth. We ultimately see his cancer journey as the greatest blessing and a catalyst for change. We feel grateful for each day after facing life and death. We no longer procrastinate or put off projects that we really want to work on and it’s given us a new drive to live life to the fullest that we didn’t have before. Writing my memoir, A Long Road to Justice, was a way of processing the trauma of the cancer journey and examining the last two decades of my career in Asia.

The pandemic hasn’t slowed us down and to our surprise, it’s been very productive with the release of my latest book and my husband had three books published during this period (he’s written a children’s and two novels as well but that’s another story about his extraordinary work ethic).

The viral news of the trafficked woman and mother of 8 children chained up in Suzhou, China has sparked a nationwide discussion in that nation – in the third year of the pandemic. Perhaps it is the fullness of time for this women’s rights issue. I wrote of a similar bride trafficking survivor I met several years ago in my book, A Long Road to Justice and the chaining of women like in medieval times and even giving North Korean trafficked brides slippers to wear while working in the fields to prevent them from running away is tragically common.

I foresee a major women’s movement rising in Asia. It feels like the time is coming – we have more women of influence in our present generation in Asia, more than at any other time. More than 100 years ago, women like me would have had bound feet, would have been considered property and not given a name until I was married, would have not been given the right to go to school, and more.

From what I hear from mainland Chinese professionals, there is indeed a growing anti-trafficking movement afoot there and I believe it’s due to the increasing influence of professional women who are outraged by the horrific exploitation of women.

Ricepaper Volume 6, Issue 1

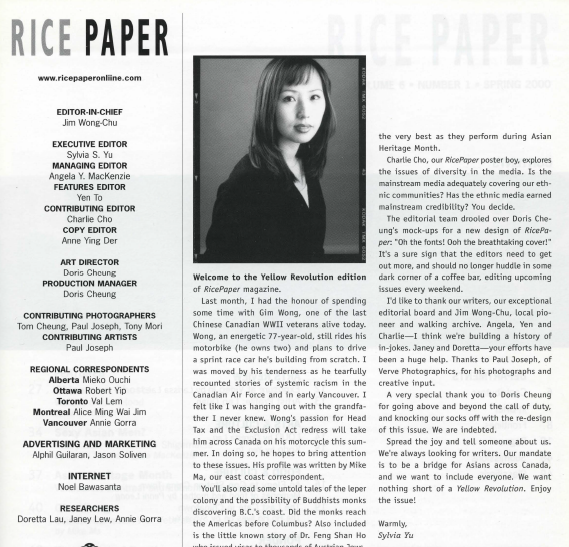

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about your experience in Vancouver. You were one of the first editors of Ricepaper Magazine. Could you tell us about your memories of Ricepaper during your time with the magazine? How did your time there shape your journey to your later work as an investigative journalist and writer?

I look back on my experience at Ricepaper with great fondness. The other core team editors Angela, Yen, and I were all just starting out in our journalism careers at the time. We were grateful to be given an unprecedented opportunity to give a platform to Asian Canadian writers and artists and untold stories about our communities. I had a simple desire to help Asian Canadians be seen and celebrated. I believe this ultimately helped me find my voice and to speak out about important human rights issues.

It’s amazing to see the incredible growth of Ricepaper magazine today and its growing international reputation. I know writers in Asia that It’s an important platform and it deserves more support.

Ricepaper Volume 6, Issue 1, circa 2000