The reading at Wesleyville.

In our article ‘The Rajah’s Son’ we explored Dave Carley’s adaptation of the story of Esca Brooke, the illegitimate son of the Rajah of Sarawak who wound up in 20th century Toronto. Here is an excerpt from his play as well as an interview with Carley.

1

Excerpt from ‘Canadian Rajah’

It is 1925. Esca Brooke has travelled to London, England. After many entreaties, Ranee Marguerite (Ghita) Brooke has finally agreed to meet him. Esca is determined to walk away from this meeting with some kind of formal recognition of his paternity; Ranee Ghita is just as determined to send him packing, empty-handed.

RANEE: Why are you here?

ESCA: I thought it was time I met my kin.

RANEE: As I said before, you still haven’t.

ESCA: With great respect, Ranee, I disagree.

RANEE: What do you want from me, Mr. Daykin?

ESCA: Brooke-Daykin.

RANEE: What do you want.

ESCA: Recognition.

RANEE: For what?

ESCA: Recognition of who I am.

RANEE: And who exactly do you think you are Mr. Daykin?

ESCA: Brooke Daykin.

RANEE: The ‘Brooke’ has made a rather recent appearance.

ESCA: The Brooke was always there. I want recognition that my father was Charles Brooke.

RANEE: You don’t want much, do you.

ESCA: There.

RANEE: There what.

ESCA: We agree on something. It actually isn’t much.

RANEE: I was being sarcastic. Recognition requires proof.

ESCA: My parentage is a well-known fact.

RANEE: One person’s well-known fact is another’s mind-boggling mystery. Concrete proof would be needed for any kind of – recognition – and, since it does not exist, that ends that.

ESCA: What would you consider concrete proof?

RANEE: We English are rather fond of documents. A birth certificate, something along those lines, which you couldn’t possibly have.

ESCA: (ESCA pulls out paper.) Perhaps a photographic copy of my baptismal record?

2

An interview with Dave Carley

I have always been fascinated by this unexpected connection between Canada and Malaysia, where I grew up. During a year I spent away from my studies, I wound up working in Edmonton where I found out about Esca’s life. Vague plans for a story took root amidst the leafy trees on Whyte Avenue. As blinding white snow set in, I confined myself to my basement and began to write, reaching back into my memories for the sights and memories of the tropics. I wanted to tell a story about Esca but it wouldn’t turn out right. I wound up focusing on his mother instead, the elusive Dayang Mastiah whose life went unrecorded, perhaps except in the diaries that Rajah Charles kept.

When writing my story I realised that everything I would write would be an invention. What I did was to recreate the world that Dayang Mastiah lived in, a fluctuating place where the power of sultans and a traditional way of life were rudely displaced by European gunships and a foreigner styling himself the king. I completed The Rajah’s Wife and it appeared online. When I left Edmonton behind I nearly forgot about it until Dave Carley contacted me out of the blue after reading the story. That is how this article came about.

Below is an interview with him.

Q. How did you learn about Esca and why did you decide to write and produce a play about him?

A. The origins of my obsession with Esca Brooke is lost a bit in the mists of time, but I do know that I have an Australian historian, Professor Cassandra Pybus to thank. I read her book The White Rajahs of Sarawak shortly after it was published by Douglas & McIntyre in 1997. The book is an immensely readable account of the Brooke family’s century-long tenure in Sarawak. But along the way, Pybus also discovered the story of Charles Brooke’s first-born son, Esca, who was sent to England, adopted, then taken to Canada.

When I tell people about this episode in our history they are always struck by the irony of a Tasmanian scholar coming here to research and reveal a story that happened in our midst. How Canadian.

One of the key things that drew me to the story – in addition to the general bizarreness of the Brookes – was the fact that Esca washed up in Madoc, Ontario. I grew up in east Central Ontario and have been to Madoc many times. I was immediately struck by the incongruity of a young man whose short life journey began in a jungle – and ended on the Canadian Shield.

Q. Was it hard to contact the descendants and how supportive were they when you first started work on the project?

A. I’ve tried tracing back through my emails but one or two computer meltdowns have interrupted the trail. However I believe that I put a mention of the story and my script-in-progress on my website, about eight years ago. A great-great-granddaughter of Esca Brooke, Sandra Huynh, was doing a bit of family googling and came upon my website and contacted me.

She in turn gave me the addresses of Esca’s two surviving granddaughters, Joan Brown and Shirley Cooke. They have been a great help to me ever since and I was thrilled that they and other descendants were able to come to the reading in Wesleyville.

Q. Aside from reading the book and speaking to the descendants, what kind of research did you conduct?

A. I have done the usual researching online, read two “autobiographies” written by Ranee Ghita Brooke, as well as other books and writings. I’ve had access to some letters by Esca, including his petition for recognition.

And then I have had to begin the hard part of any historical adaptation – the process of “shaping the story” while remaining true to it. For the dramatic arc of my play Canadian Rajah, Esca’s long, long quest for recognition is not dramatic. So the biggest dramatic change is that I set the play within the context of a disastrous meeting in London, England between Esca and Ranee. In real life, it was Esca’s wife Edith who made the journey across the Atlantic to meet with Ranee Marguerite Brooke (also referred to as Ranee Ghita).

There are a few other events for which I have no clear answer, and have resorted to what I would call “informed speculation”. For example, I am still not sure when Esca discovered his true parentage and when he found out that payments had been made to his adoptive parents, presumably to keep him in Canada and safely out of the Brookes’ hair.

But the vast majority of the text is true. And that’s almost the biggest challenge the story of Esca Brooke poses – convincing an audience that his journey actually happened.

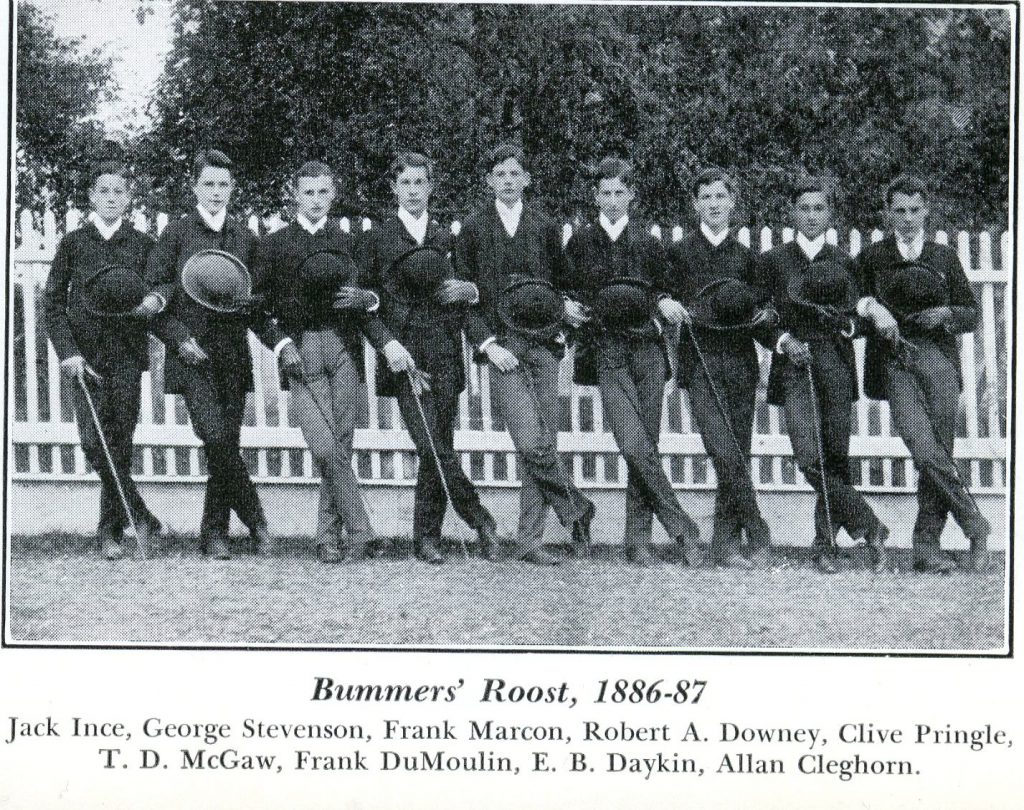

A humorous sidebar to that is Esca’s time at Trinity College School in Port Hope. By Esca’s account – and judging from pictures supplied by the TCS archives – it was happy time. One informal group Esca belonged to adopted stylish clothing and would sashay about downtown Port Hope – a kind of Victorian era version of the Mods. The fellows called themselves The Dudes. I couldn’t resist putting this in the Wesleyville draft. But when it was read aloud, I could feel the audience going “huh?” The word ‘dude’ seems so utterly modern – so Keanu Reeves – that I could tell the audience quite naturally felt a gross historical inaccuracy had been handed them for some unfathomable reason. And it would make them doubt the other “real” content. So I think I’m going to take it out, but reluctantly.

The Dudes.

Q. Canadian Rajah has been in the works several years (a decade, I believe?) now. Why has it taken so long and was it difficult to keep the momentum going?

A. The story of Esca and the Brooke family is a daunting one – because of its sheer vastness. I have taken various runs at the story, bringing in more of the Brooke backstory in the beginning. But the cast size would quickly spiral out of control, as did the sheer amount of story. I knew that if the play covered all the Brookes and Esca, I ended up doing no one justice. I stopped working on the play many times out of frustration.

But of course I could never forget the story, or Esca. And finally I realized it was Esca’s story that initially drew me to the saga, and that the pre-story of the Brookes (colourful though it is) was irrelevant to that dilemma of a man seeking to establish his identity.

Once I had made the decision to concentrate on Esca, the issue became what was the central struggle that he faced in his life. And, even here, there was much to deal with. But after research and conversations with his granddaughters, I concluded it came down to two things: the fact that he had two fathers, both of whom treated him badly – and the quest for recognition that consumed his later years.

Q. You specifically mentioned Esca’s garden in Toronto in an earlier email. Was there something about this garden in particular that stood out to you? I remember it being mentioned in the ‘White Rajahs’ book.

A. Esca was a prize-winning horticulturalist and, by all accounts, created a magnificent garden at his home in Lawrence Park. He lived in two homes there over a number of decades, and I have been up to see them, in the hopes I could traipse around the yards. Alas, there has never been anyone at home when I’ve visited so I didn’t go into the backyards. I am curious to see if there are any remnants – a bush or rockery or old roses, perhaps – that is left over from Esca’s time. The houses have both been renovated, one fairly extensively, so I suspect nothing remains. Still, I’d like to go and just stand there. His granddaughters told me that their brother often went over to the house to help Esca with the heavy work and lawn mowing.

Q. In January your play will finally be completed and premiered! Now that your long project is almost at an end, do you have any thoughts and opinions that you’d like to share?

A. The play is actually not quite at full premiere state. What we are trying is a variation on the play development process, doing a series of public readings that edge closer and closer to a full staging. In August 2016 we had a formal reading at the Wesleyville Church arts centre, near Port Hope. The heat that night was Sarawak-humid and a full house heard renowned actors Chick Reid and Richard Lee read the play, standing at music stands.

In January of 2017 we will perform Canadian Rajah again, twice, at the Warkworth Arts Centre. I will have done a rewrite of the script, incorporating many changes I learned from the Wesleyville reading. The actors will be in costume. There will be some movement, as well. The actors will still be working from scripts, however.

I anticipate that, following Warkworth, I’ll do another reading and then the play will be ready for a full production. I have my eye on a couple of possibilities for the fall of 2017 in Toronto, which I would like to meet because next year is the 150th anniversary of Esca’s birth. And, after his first years in this country wandering about the Canadian Shield, Esca settled in Toronto. It was also from Toronto that he pursued his long, frustrating and futile quest for recognition. It seems fitting that I offer up his vindication here, in his adopted home city.

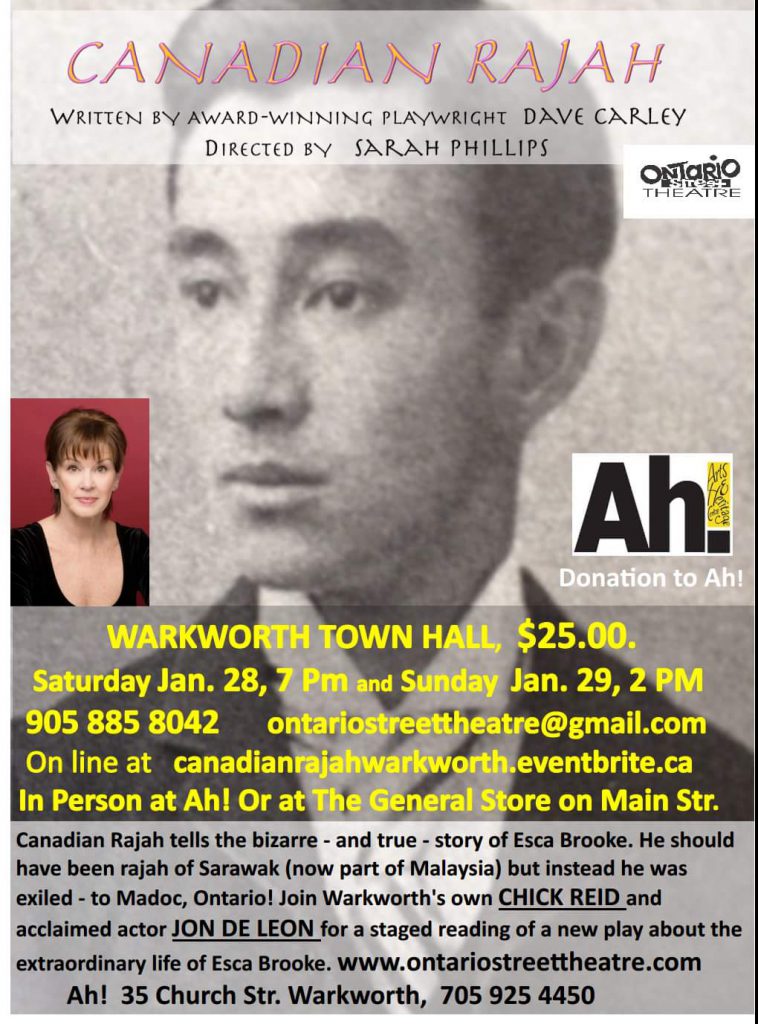

Dave Carley’s Canadian Rajah is currently still in production, with a reading scheduled for January 28th (evening) and 29th (matinee) at the Warkworth Town Hall Centre for the Arts. Since Richard Lee will be with a production of Kim’s Convenience, and the play will be headlined by Jon de Leon and Chick Reid. The poster and the photograph from the reading courtesy of Dave Carley. Photograph of The Dudes courtesy of Viola Lyons from the Trinity College School.

1 comment

Last night (march 8, 2020) I attended a production of Canadian Rajah with my wife Joan. Randy Reid’s New Stages mounted the production at the Market Hall in Peterborough. Jon de Leon and Barbara Worthy played Esca and Ranee Ghita. The play was excellent, made more so because it is based on a little-known true story with local references.