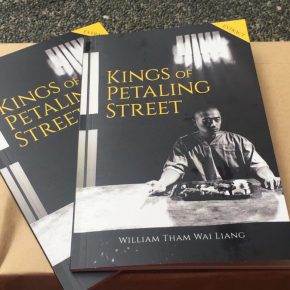

The long-waited release of William Tham Wai Liang’s debut novel Kings of Petaling Street has finally arrived and available in bookstores. Even the family of the most powerful kingpin of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown cannot be immune from danger when confronted by ambitious men who thirst for power. The narrative follows one notorious gangster Wong Kah Lok, the infamous “King of Petaling Street,” who desperately shields his own son from his criminal legacy but realizes the futility of it all as encounters an existential crisis. This stylishly written film noir has been on Ricepaper’s must-read list for a while, so now that it’s finally published by Fixi Novo, we reached out to William for an interview before he hits the road on his book tours.

Kings of Petaling Street is a novel published by Fixi Novo in 2017.

Ricepaper: Your book is something out of a Johnnie To or Park Chan-wook film, raw with tension and struggle. What inspired you to write this story?

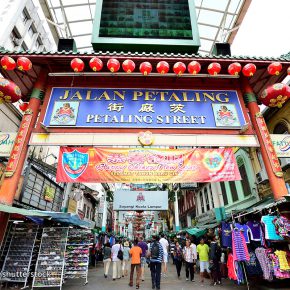

William: In the fall of 2013, I was going through a particularly unhappy time and writing stories was a good escape. Added to the that was the fact that it had been a bad year for Malaysian news, with a string of assassinations and a messy General Election creating an angry and passionate atmosphere. I couldn’t write about politics but a crime thriller seemed like the next best way to vent my frustrations. Malaysia’s troubled recent history served as an inspiration for this book, alongside my dad’s stories about growing up in Chinatown.

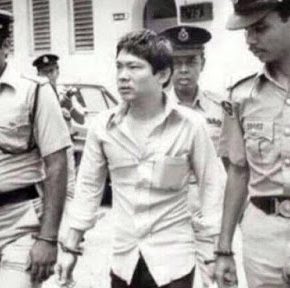

Botak Chin

Ricepaper: Your novel drew inspiration from Malaysia’s most notorious and deadliest gangster, Wong Swee Chin aka Botak Chin. What type of research did you do to translate real life into fiction? What’s some advice that you can tell other emerging writers who have an idea about a real life story or incident and want to turn into a fictional story?

William: In order to tell the story, it was important to understand Botak Chin and his motivations. My character, Wong Kah Lok, ended up being loosely based on him since I played fast and loose with the facts. As far as research was concerned I mostly took inspiration from real-life exploits and meshed them together in different permutations. Since Botak Chin was eventually executed in prison, Wong Kah Lok is effectively an imagining of Botak Chin had he survived and lived to an older age. When it comes to adapting real-life events or people into stories, I find it important to remember that the act of doing so is an appropriation of sorts. It becomes a question of what qualifies a writer to tell someone else’s story as their own. This is a complicated issue and the best example I can think of is Vedran Smailović, who was adapted into a character in the novel The Cellist of Sarajevo. In my case I did not want something like this to happen, so instead I just worked very loosely with a few key facts to come up with something that, while not quite original, was different.

Petaling Street, in Kuala Lumpur

Ricepaper: How long did it take you to complete it, from conception to printing? Was there any particular part of the process of your writing this book that took the most time to do?

William: Three years. Six months from the conception of the idea to the end of the first draft. Another six months was spent waiting for a response from the publisher. More than half a year passed before I received news that the book project was going ahead, and when all the edits were eventually completed one and a half years had passed. The editing took the longest time. After the edits were made, the book was only two-thirds as its original length!

Ricepaper: You completed this book while still a full time student. What advice can you give writers who might be a full time student or working full time?

William: Always keep writing. Never stop. Persevere.

Ricepaper: Has any films or novels particularly influenced your work over the years? Who are some of the writers that you look to for inspiration or style after?

William: This book in particular drew inspiration from the following films: ‘The Godfather’ with its epic scale, the peculiar mood of Dain Iskandar Said’s ‘Bunohan’, while the look and feel of a fictionalized Kuala Lumpur was a blend of images from ‘Only God Forgives’ and ‘The Raid: Berandal’. However, much of my writing style is influenced by the beautiful descriptions of Tash Aw (The Harmony Silk Factory), JG Ballard’s disturbed visions (Empire of the Sun), and Ernest Hemingway’s lyrical straightforwardness (A Moveable Feast).

William Tham Wai Liang

Ricepaper: Zen Cho has said your book is ‘Stylish, dark and compelling, Kings of Petaling Street is an elegant meditation on the cycle of violence.” Why is violence a theme of the book? What do we learn from the conflicts conflicts that arise when the King of Petaling wants to protect himself and his family from his rivals?

William: Since I wrote the book with the intention to pitch it to Fixi, the nature of violence seemed like an excellent theme to write about. Beneath the surface, Malaysia is fraught with unease, with stories of casual violence often appearing in the news. Wong Kah Lok basically enters a life of crime when an act of violence strikes home, and his subsequent revenge triggers a retribution that carries forward through generations, therefore revealing the inescapable nature of violence. I suppose in this story we learn that there is no escape from past. Eventually it always comes back to haunt you.

Ricepaper: What would you ultimately like your readers to get out of this book?

I hope that they get a few good hours of entertainment! And perhaps a slightly better understanding of Malaysia’s urban landscape.

Ricepaper: You’re a Malaysian Canadian writer who have traveled extensively around the world, much like another Southeast Asian writer Goh Poh Seng, who settled in Canada and continued his writing. He left Singapore upon political upheaval. How do you relate to him and others of his generation of writers?

William: While I know that Goh Poh Seng grew up in Kuala Lumpur, and that he eventually became a Singaporean (and eventually Canadian) citizen. He falls into a group of early postcolonial writers whose style I don’t exactly relate to, largely because of how different the subject material that they deal with is from what I like reading and writing about. I relate to more contemporary writers, particularly the ones who work with Fixi. However, I do admire the work that they did but it’s sad that they are not as well known as they should be due to an almost-nonexistent literary scene.

Ricepaper: Who are some Malaysian English language writers viewed as pioneers of literary writing in Malaysia?

William: K.S. Maniam and Shirley Geok-Lin Lim spring to mind. But sadly the Malaysian English literary scene seems to have been lacking due to various factors until relatively recently (unless you count nonfiction writers such as Syed Hussein Alatas). More recent names would include Tash Aw, Tan Twan Eng, Preeta Samarasan, and Zen Cho (Farish Noor if we count nonfiction). I would say that Tash Aw really put Malaysian writing on the map with his first novel. It was certainly a huge inspiration to me.

Ricepaper: What is your next project going to be about?

William: I just completed a draft of a semi-autobiographical novel after five years. I am also planning a novel that explores lingering fears of Communism set against the beginning of Prime Minister Mahathir’s sparkling, artificial dreams for a new Malaysia.

Ricepaper: You’re an editor at Ricepaper Magazine, and you volunteer your time with the Asian Canadian Writers Workshop and LiterASIAN festival. In your time as an active participant in this writing community, how has your writing changed? Do you feel you’ve made an impact in other’s writings?

William: I have become more careful with my writing. Words are never just words. They come loaded with meaning and implications. I have also learned how important it is to fact-check, especially in a post-truth world. I like to think that I’ve made a difference in someone else’s writing, because ultimately that’s what my role in Ricepaper is all about.

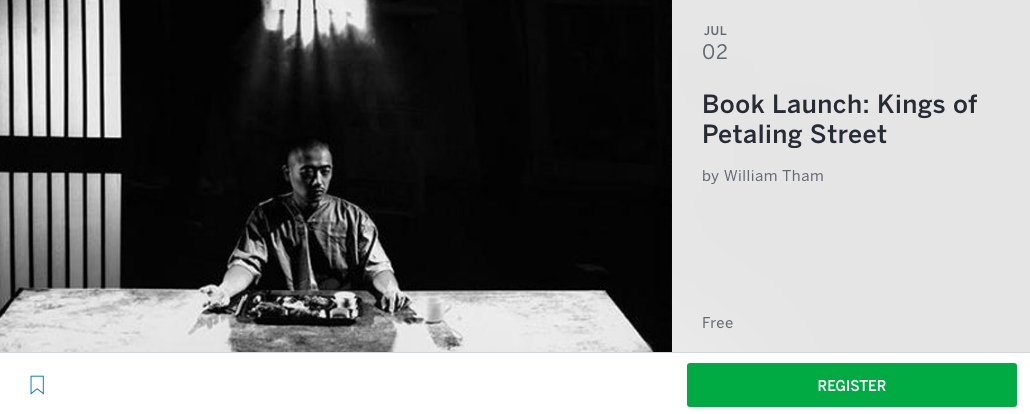

The photograph by Wong Hoy Cheong is used as the front cover of the novel. Last Supper; Chronicles of Crime.

Join William Tham and Ricepaper on Sunday, July 2, 2017, at 5.30pm at the Paper Hound Bookshop on 344 West Pender Street, in Vancouver, BC. There will be a short reading, a discussion of the book and contemporary Malaysian/Southeast Asian pulp fiction, and refreshments will be provided. Also featuring talks by Karla Comanda and Gavin Hee.