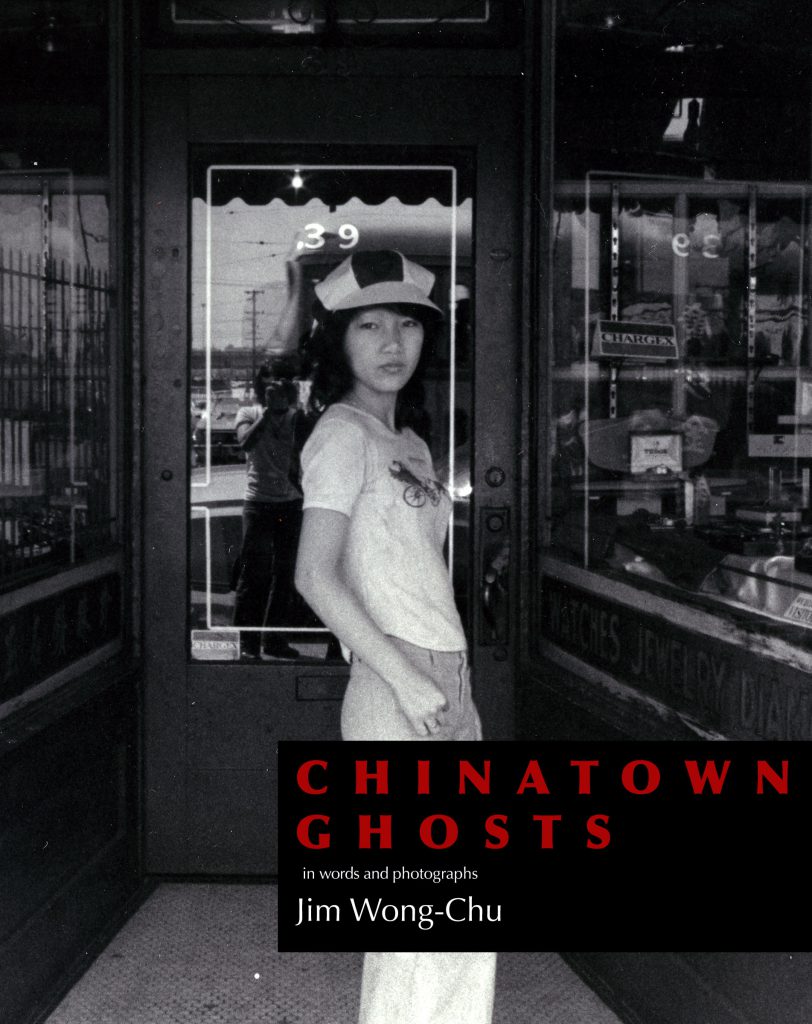

Chinatown Ghosts, originally published in 1986, is a collection of poems that Jim Wong-Chu wrote over a period of years. Some of them were later published in Ricepaper. I encountered Chinatown Ghosts during a visit to the UBC Rare Books and Special Collections Library to conduct research in the Jim Wong-Chu fonds. What I found particularly striking about the collection was how Wong-Chu captures lived experiences through his use of poetry to express the complex and entangled layers of history, as well as the emergent structures of feeling through which Chinatown continues to rear its ghostly presence. The literal and metaphorical translation of experiences and histories through the explicit discussion of Chinese immigrant histories and the figure of the ghost reveals the affective reverberations and gaps in Chinese Canadian identity formations.

Chinatown Ghosts, originally published in 1986, is a collection of poems that Jim Wong-Chu wrote over a period of years. Some of them were later published in Ricepaper. I encountered Chinatown Ghosts during a visit to the UBC Rare Books and Special Collections Library to conduct research in the Jim Wong-Chu fonds. What I found particularly striking about the collection was how Wong-Chu captures lived experiences through his use of poetry to express the complex and entangled layers of history, as well as the emergent structures of feeling through which Chinatown continues to rear its ghostly presence. The literal and metaphorical translation of experiences and histories through the explicit discussion of Chinese immigrant histories and the figure of the ghost reveals the affective reverberations and gaps in Chinese Canadian identity formations.

Although Chinatown continues to exist, it remains a site of debate. We see continued attacks on Chinatown through gentrification: As of 2017, five proposals have been made to build condos at 105 Keefer, and according to by Hua Foundation, long-established local greengrocers, barbequed meat shops, dry-goods stores, and fishmongers in Vancouver’s Chinatown are faced with high rates of closure. Likewise, unfounded accusations of unsafe food practices by city health officials in the 1970s led to numerous temporary closures of the aforementioned barbequed meat shops, while redevelopment and beautification projects from the 80s threatened community members. But what else can we learn from these ghostly presences that linger and disrupt discrete notions of past, present and future in the production of the Chinese Canadian subject and community?

Chinatown Ghosts begins with a poem titled tradition, describing the process of consuming joong—savoury gluitinous rice packets that are often filled with salted duck yolk, pork, dried shrimp, mung beans, and mushrooms. It is through “unlocking” and “releasing the long thin strand/ which binds” histories, imaginings, desires and collective traumas that identity reclamation is framed as both an opening up and revealing of the individual. Enmeshed in a complex web of relationships with family, nation and place, self-identity and community, ghosts emerge.

Many of Wong-Chu’s poems are implicative of the history of early Chinese migration and involvement in the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the mining industry, as well as questions of identity and navigating trauma. In the poem fourth uncle, Wong-Chu shows the importance of desire as it emerges from the legacy of these histories. The poem is about the relationship between a village relative and the persona, a young boy, the former who has returned to the West Coast to die and be buried in the old Chinese cemetery, buried alongside his companions in the direction ‘facing home’ alongside his companions in the old Chinese cemetery. This leads the boy to ponder about his own future and feelings of distance from his uncle, open-endedly leaving readers with the question: Where will the boy choose to die when the time comes? This sense of ambiguity captures the complexities of narratives of ‘belonging’ that have emerged out of histories of migration for settlers of Chinese ancestry through economic coercion and / or the desire for ‘upward mobility’ through complicity in indigenous dispossession—highlighting the connections between the formation and legitimation of the Canadian state and the practices and histories through which diasporic identity formations emerge in relation. The boy’s uncertainty and the presentation of affect moves away from taken-for-granted narratives of assimilation that necessarily pit first-generation immigrants against successive generations. This presents the possibility of considering the simultaneous feelings of ‘in-betweenness’ and questions of identity, community, and desire with more nuance. The literary translation of both the literal and affective traces of the past that have merged with the present are heavily implicative of death and loss, as it is commonly used to describe the current state of Chinatowns that are faced with the threat of gentrification, a denial of their futurity. However, the continued presence of Chinatown ghosts, despite their association with death, can be reconfigured as a liminal figure. The complexities of the figure of the ghost and the haunting metaphor functions can function as not only something to be feared of the uncertainty that they present but also something to reconcile with in thinking through the spatialization of Chinatown as well as bodies in the (re)formation of communities across generations, migration, and displacement.

Jim Wong-Chu

The figure of the ghost as a carrier of these historical legacies is one that rejects the institutionalized violence of modernizing projects because of its continued refusal to ‘disappear’ or lose significance despite attempts at erasure and negation. However, its presence should not necessarily be taken for granted. The speaker’s search for “scraps/ of memory” above earth under which the bones of golden mountain men lay in old chinese cemetery – kamploops july 1977 and questions of what healing looks when recognizing “our own ways/ of mistreating ourselves” in the poem not the first time for its presentation of the desire to retrieve “lost time” breaks the illusion of the Chinese Canadian as ‘just is’ and as neatly emerging out of a complicated history. But what does it mean to try to retrieve “lost time” in relation to experiences of disconnect that come out of our haunting? In an early manuscript of Chinatown Ghosts where Wong-Chu had used a stage-play format that included notes about sound effects, music and additional intermittent narration. The speaker of each poem was explicitly gendered; in the case of old chinese cemetery, the speaker is named as ‘female,’ knowledge that gives new meaning to the narrator’s experience of disconnect as well as the possibility of considering changes to immigration policies and migration patterns in relation to the gender and sexual politics of the development of the ‘Chinese Canadian.’ The old man’s lover in scenes from the mon sheong home for the aged is presented as claiming to have the ability to sense ghosts, although she is not taken seriously. With the cause of her missing items “lurking in the shadows” and “her tongue” as her only defense, she is put in a position where she must prove her experiences to members of her community. Ghostliness not only emerges out of the portrayal of histories but also the gaps in representation. Men are a central figure in the genealogy and partial memory of the Chinese Canadian as opposed to women. The erasure of the legislative construction of Chinese women who are both constructed relationally to Chinese men and White women invokes and legitimizes heteronormative and racist ideologies that are productive of the partial memories and histories of the formation of the Chinese Canadian, who must be figured and proved as loyal to the Canadian state, obscuring experiences of violence and trauma.

How do we navigate and respond to feelings of longing, pain, and questions of connection and disconnection that emerge out of our encounters with ghosts? The development of relationships through a shared understanding is an important reoccurring theme in Chinatown Ghosts as they reveal the productive possibility of solace, love, and affection in reconciling with experiences of haunting. Warmth emanates from Wong-Chu’s poem dreams, my favourite from the collection, as its speaker presents a promise of support. Addressing an unknown subject, “waiting/ ready to catch you/ as you fall” when you reach the threshold between that which is and is not discernible, the poem effectively shows the significance of shared understandings as a source of comfort and legitimation. Similarly, Wong-Chu produces a delightful image of artists coming together in his poem “medley in ink and brush,” where they are “bond[ed] . . . like bamboo brush and cuttle ink/ to the soft rice paper.” He beautifully describes the physical and psychic intimacies of writing, from brush to paper and the coming together of artists, a process through which “bodies emerge”—remaining singular yet retaining all of their complexities. Thus, the possibilities of emergent feelings of anger, confusion, happiness and grief and the ability to be vulnerable and transparent with others are not a sign of weakness, but as a site of potential creativity and care, is reflected by the multifaceted nature of the ghost as a figure does not necessarily need to be defined by or limited to death. Wong-Chu’s work opens up the possibility for dialogue about the effects of histories and continued institutionalized of forms of racism, alongside understanding and affirming experiences of incoherency and moments of clarity in our relationships with ourselves and our communities.

Chinatown Ghosts, 1st edition (1989)

Reconciling the presence of ghosts with our own ghostliness and experiences of being haunted through the translation of experiences and histories through the translation of the affective, the accumulation of feeling that emerges out of and through experiences of partial memory reveals the fluidity of the ghost figure, transposed onto bodies, spaces and objects through which they persist. Despite the undesirability of haunting for its liminality and the fragmentation of memories, it presents a challenge to narratives of identity that rely on respectability politics with the effect of illuminating on histories that have been made obscure and presenting the possibility of navigating experiences of loss, disconnection, and shame. The ghost is fluid in the ways by which it emerges out of the traces that we leave behind and that accumulate in processes of displacement, spatializing and the formation of diasporic communities. Haunting reveals the instability and artificiality of belonging, for what the ghost is and isn’t and the ways in which it is a rejection of the notion of modernity wherein the ‘present’ is understood as separate from the past and what we believe to be the future

Chinatown Ghosts will be republished by Arsenal Pulp Press in September 2018 and launched at the LiterASIAN festival in September 2018.

Miranda is a queer second-generation Chinese settler on Coast Salish territories. She is completing her fourth-year at the University of British Columbia, majoring in Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice and minoring in Asian Canadian and Migration Studies. Likes cats and dogs equally.