As a translator of Chinese comics and folk rock who lives in Vancouver, BC, Nick Stember is an expert of Chinese comics, or manhua. In addition to building the world’s first English language encyclopedia of Chinese comics and animation, the Encyclopædia Manhuannica 漫畫百科, Nick is a consultant for a variety of ventures, including Storycom and Clarkesworld Magazine’s Chinese Science Fiction Translation Project and the Grayhawk Agency and the Ministry of Culture (ROC)’s Books from Taiwan Vol. III: Comics. Ricepaper took the opporunity to interview Nick Stember about the world of manhua and its significance in the history and future of storytelling in Asia. This is the second of a two-part interview series with Nick Stember.

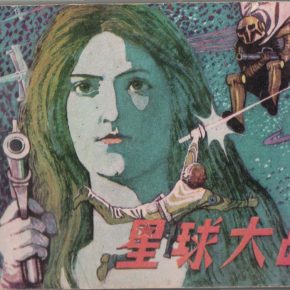

In the 1980s there was an enterprising press in Guangzhou that put together a lianhuanhua of a popular Western movie Star Wars –that had come out three years before in the US. You’ve even translated the comic book from Chinese to English. What can we learn from these old comics of the time? What were the political, social, and political implications of the creation of these comics?

The Star Wars comic drawn by Song Feideng has a really great backstory. Maggie Greene, a historian of the at the University of Montana picked it up on a whim at the Confucian Temple flea market in Shanghai while doing research in China a couple of years back. Her research looks at supernatural operas in from the Mao-era, and so lianhuanhua play an important role in understanding how these stories were circulated during a time when the average person didn’t have a TV and movie theatres were basically only available to a very small segment of the population. Live performances were one solution, as were mobile theatres, and lianhuanhua were another. There are stories from the late 1970s that talk about lianhuanhua being passed out on trains and then collected at the end of the trip. They were an extremely cost effective way of not only distributing propaganda, but also providing analog entertainment in the pre-digital age.

The Star Wars comic drawn by Song Feideng has a really great backstory. Maggie Greene, a historian of the at the University of Montana picked it up on a whim at the Confucian Temple flea market in Shanghai while doing research in China a couple of years back. Her research looks at supernatural operas in from the Mao-era, and so lianhuanhua play an important role in understanding how these stories were circulated during a time when the average person didn’t have a TV and movie theatres were basically only available to a very small segment of the population. Live performances were one solution, as were mobile theatres, and lianhuanhua were another. There are stories from the late 1970s that talk about lianhuanhua being passed out on trains and then collected at the end of the trip. They were an extremely cost effective way of not only distributing propaganda, but also providing analog entertainment in the pre-digital age.

The Star Wars comic is a relic of the transition from a command control economy to the market economy. They were published by an education press—traditionally science fiction in China has been treated as a way to promote science and technology. But obviously there was commercial side to this too, because by the late 1970s people were reading about all the latest Hollywood films, many of which were being screened just over the border in Hong Kong. This was actually something that had been going on since the Republican-era, when the first film magazines started appearing in the 1920s. And of course at the time many Hollywood films were screened in Shanghai, but the ones that weren’t got written up and discussed, so there was a very active film appreciation culture in China from early on. Lianhuanhua are one facet of this tradition, making films available to audiences who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to see them. This was especially true in during the ‘reform and opening’ period of the 1980s, when everything from Tintin to ET to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were adapted to lianhuanhua. Eventually of course they lost out to the real thing, as TVs and movies started to become easier to come by as incomes rose and prohibitions against imported media loosened. Nowadays they’ve had a come back with collectors, and there have been reprints of some of the more popular works, but as far as I know no one is making new lianhuanhua, so it’s basically become a moribund genre of cultural production.

The other important side to the Star Wars comic is how it fits into the history of Chinese science fiction, which is very much alive and thriving today. You can actually trace the history of sci fi in China all the way back to the late-Qing, with translations of Jules Verne appearing, and also domestic stories about going to the moon and other scientific romances. During the Republican era, sci fi got used by Lao She in his novel Cat Country to satirize the infighting between warlords, and the effect of foreign occupation on (what he saw as) ossified cultural traditions.

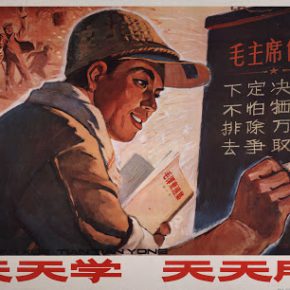

Post-1949, science fiction in the PRC moved into the previous mode, with stories about pigs the size of elephants and giant watermelons—basically promoting the idea that China was going to leap frog capitalist countries by relying on the wisdom of the masses. In a way you could say the whole Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s was an act of science fiction, albeit one with terrible consequences for some tens of millions of people. During the Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s, which grew out of a power struggle between Mao and the CCP following the massive failure of the Great Leap Forward, science fiction was banned along with pretty much everything else aside from Jiang Qing’s model operas. But when the Cultural Revolution ended in the mid-1970s there was a huge resurgence of interest in science fiction and utopian visions of the future.

Post-1949, science fiction in the PRC moved into the previous mode, with stories about pigs the size of elephants and giant watermelons—basically promoting the idea that China was going to leap frog capitalist countries by relying on the wisdom of the masses. In a way you could say the whole Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s was an act of science fiction, albeit one with terrible consequences for some tens of millions of people. During the Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s, which grew out of a power struggle between Mao and the CCP following the massive failure of the Great Leap Forward, science fiction was banned along with pretty much everything else aside from Jiang Qing’s model operas. But when the Cultural Revolution ended in the mid-1970s there was a huge resurgence of interest in science fiction and utopian visions of the future.

One project I’ve had on my to-do list for a couple of years now is a translation of Ye Yonglie’s Smarty Pants Visits the Future, which was one of these wildly popular stories that captured the imagination of young people at the time. The original Star Wars trilogy has never been screened in China to my knowledge, and the prequels weren’t either. So lianhuanhua allowed Chinese sci fans take part in the global phenomenon of Star Wars before bootlegged VHS tapes and DVDs started circulating. But of course now that it’s available online and in English, the Chinese Star Wars comic has gotten a lot of attention for how unfaithful it is to the original, at least visually—Chewbacca is a monkey, Obi Wan is a Jedi ‘knight’ on a rocket powered motorcycle (ripped from a poster for the David Carradine vehicle Deathsport), and Darth Vader wants to use the Death Star to attack Florida. So now we have these cultural flows coming full circle, from North America over to China and then back again.

Few figures in Chinese mythology seem better suited to being adapted to cartoons than the Monkey King, Sun Wukong 孙悟空. There’s so many that we can draw from, but perhaps you can give us your take on what you call the “granddaddy” of all Monkey King adaptations, Princess Iron Fan?

In a way you could say Japanese manga and anime developed out of Chinese comics and animation. But of course the Wan brothers were inspired in large part by Disney and consciously modeled their depiction of Sun Wukong on Mickey Mouse, and Princess Iron Fan on Snow White. They even used rotoscoping, or drawing on top of live action film, which is the same technique that Walt Disney used to speed up the production of Snow White. If you look closely, in parts of the movie you still see the actor’s eyes peeking through. And then later, when Te Wei was learning the basics of animation in the late 1940s, he studied under pioneering Japanese animator Tadahito Mochinaga, who ended up spending the last years of WWII in Manchuria. Along with a number of other Japanese filmmakers, Mochinaga and his wife decided to stay in Changchun following the Japanese surrender in 1945. So there was a lot of back and forth between China and Japan, and Asia and Hollywood. And then later between China and Soviet Union.

In a way you could say Japanese manga and anime developed out of Chinese comics and animation. But of course the Wan brothers were inspired in large part by Disney and consciously modeled their depiction of Sun Wukong on Mickey Mouse, and Princess Iron Fan on Snow White. They even used rotoscoping, or drawing on top of live action film, which is the same technique that Walt Disney used to speed up the production of Snow White. If you look closely, in parts of the movie you still see the actor’s eyes peeking through. And then later, when Te Wei was learning the basics of animation in the late 1940s, he studied under pioneering Japanese animator Tadahito Mochinaga, who ended up spending the last years of WWII in Manchuria. Along with a number of other Japanese filmmakers, Mochinaga and his wife decided to stay in Changchun following the Japanese surrender in 1945. So there was a lot of back and forth between China and Japan, and Asia and Hollywood. And then later between China and Soviet Union.

Daisy Du at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology has done a lot of the groundwork on the history of animation in China and is preparing to publish a monograph on the subject soon, I believe. Eileen Chow at Duke has also been working in this field for some time now, and did a presentation on animated adaptions of the Monkey King at AAS in Seattle last year. The whole area of contemporary cultural production around Journey to the West is surprisingly understudied, I think in part because it seems so obvious. But the curious thing for me is what is driving the seamlessly endless popularity of the Monkey King? As I’ve hypothesized on my blog, and in talks I’ve given, the Monkey King is a sort of ur-cartoon figure, in the same way that other trickster gods like Coyote or Raven is for the First Nations peoples here in the Pacific Northwest, or Anansi is in West Africa and the Caribbean. The temptation to animate him is just too good to pass up.

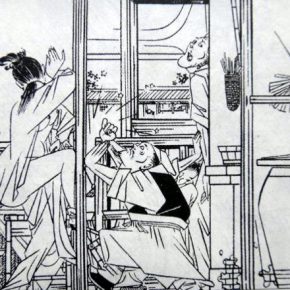

The Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅 is a notoriously pornographic vernacular Chinese novel believed to date from the late sixteenth century. For better or worse the Jin Ping Mei has come to be known mostly for the dirty bits. Your research has delved into the murky world of comic book adaptations of the great novel. Can you tell us more about this really sordid but interesting development in the world of Chinese comics?

I first got interested in the Jin Ping Mei thanks to a course I took at UBC with Catherine Swatek, whose cousin, David Roy, happens to have completed the first English language translation of the book. It took him almost 30 years to finish it, working in the summers and teaching at the University of Chicago the rest of the year. Professor Swatek also specializes in a somewhat sordid text—The Peony Pavilion, an opera about love and sex and all sorts of things that people were going crazy over even way back in the Ming dynasty when opera really at its peak and copies of the Jin Ping Mei were flying off the shelves. The Jin Ping Mei is infamous for, as you put it, ‘the dirty bits’ but there’s also an incredible amount of information about the material culture of the Ming that’s been preserved in the text, everything from the food they ate to the clothes they wore to the way they built their houses.

I first got interested in the Jin Ping Mei thanks to a course I took at UBC with Catherine Swatek, whose cousin, David Roy, happens to have completed the first English language translation of the book. It took him almost 30 years to finish it, working in the summers and teaching at the University of Chicago the rest of the year. Professor Swatek also specializes in a somewhat sordid text—The Peony Pavilion, an opera about love and sex and all sorts of things that people were going crazy over even way back in the Ming dynasty when opera really at its peak and copies of the Jin Ping Mei were flying off the shelves. The Jin Ping Mei is infamous for, as you put it, ‘the dirty bits’ but there’s also an incredible amount of information about the material culture of the Ming that’s been preserved in the text, everything from the food they ate to the clothes they wore to the way they built their houses.

It’s also a biting social satire, and Roy’s translation does a superb job of showing how thinly veiled the author’s barbs were in some points of the novel, even if they seem cryptic to us now. The comics I tracked down don’t really take themselves seriously in the same way the novel does, of course. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say they take the same half-serious tone, but they don’t challenge the status quo in the same way the original did. Arguably, Jia Pingwa adapted the novel to a modern setting in his own infamous ‘dirty novel’ Ruined City, which was inspired (in part) by reading a bootleg copy of the Jin Ping Mei in the late 80s (the book was still banned in China at the time). Howard Goldblatt’s translation of Ruined City was just published in January of this year. Super worth checking out. (Full disclosure: I am translating Jia’s latest novel The Poleflower as part of a project I’m spearheading to get more of Jia’s work published in English.)

One of my favorite adaptations of the Jin Ping Mei that I found was a ‘boys love’ manga that creimagines the story being about a man with a harem of beautiful boys rather than voluptuous women. Since gender politics play such a key role in the original novel, I found the idea of eliminating the women entirely interesting on a whole bunch of levels. Also, since the author of that adaption was Japanese, it opened up questions about the reception of Jin Ping Mei outside of China, and how much easier it is for creators outside of the PRC to do adaptations of classic texts that keep all of the original sex and violence—all of the film adaptions of the Jin Ping Mei that have been made to date were produced in Hong Kong. I’m not sure I’ve been able to answer those questions yet, but they would be interesting avenues to pursue for scholars with the language skills to do research in Japanese and Cantonese.

Who are some of the contemporary comic artists that we should look out for in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan for those who want to begin learning more about Chinese comics? Are the English translations of these comics easy to find in bookstores or online stores? Where can we find them?

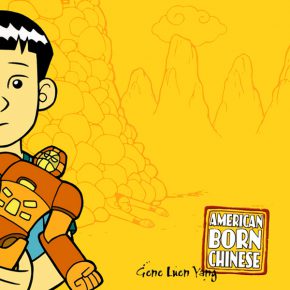

As far as contemporary comic artists go, it really depends on what you are looking for. One of the most unique groups is the SC Manhua, or Secret Comix group which has been putting out massive tomes of underground DIY comics for a couple of years now. Some of the best and most innovative artists working in Chinese language comics today have contributed to SC Manhua anthologies: Little Thunder, Chi Hoi, Kongkee, Yan Cong, and many others. In terms of more traditional narrative and autobio comics, Li Kunwu and Phillipe Otie’s A Chinese Life is a good place to start, and has been translated into English (and actually into Chinese, since it was originally published in French). Bella Yang has published some really great comics about her experience of living in China in the 1980s as a second-generation Chinese-American, and those are in English. And Gene Yang is also of course an amazing storyteller who has done an incredible job of sharing his experience of growing up Chinese in America in his book American Born Chinese, which also features the Monkey King playing a key role. More recently he has been working on a project with DC on a spinoff of Superman, with the hero hailing from Shanghai rather than Smallville. Ethan Young is another Chinese-American cartoonist who has been working to tell Chinese stories in the comics medium with his graphic novel Nanjing: The Burning City, published just last year by Dark Horse.

As far as contemporary comic artists go, it really depends on what you are looking for. One of the most unique groups is the SC Manhua, or Secret Comix group which has been putting out massive tomes of underground DIY comics for a couple of years now. Some of the best and most innovative artists working in Chinese language comics today have contributed to SC Manhua anthologies: Little Thunder, Chi Hoi, Kongkee, Yan Cong, and many others. In terms of more traditional narrative and autobio comics, Li Kunwu and Phillipe Otie’s A Chinese Life is a good place to start, and has been translated into English (and actually into Chinese, since it was originally published in French). Bella Yang has published some really great comics about her experience of living in China in the 1980s as a second-generation Chinese-American, and those are in English. And Gene Yang is also of course an amazing storyteller who has done an incredible job of sharing his experience of growing up Chinese in America in his book American Born Chinese, which also features the Monkey King playing a key role. More recently he has been working on a project with DC on a spinoff of Superman, with the hero hailing from Shanghai rather than Smallville. Ethan Young is another Chinese-American cartoonist who has been working to tell Chinese stories in the comics medium with his graphic novel Nanjing: The Burning City, published just last year by Dark Horse.

As you can see from above, most of my recommendations are for books originally published in English rather than translations. There really haven’t been very many translations of Chinese comics published, aside from some efforts by Jademan to push wuxia comics in North America back in the 90s. Since last year, Books from Taiwan, which is financed by the Ministry of Culture (RoC), has been doing an annual anthology of samples from the latest and greatest in Taiwanese comics, translated and lettered by yours truly. So that’s a great resource to check out if you want to get a taste for what’s out there, and I’m hoping I can find a way to finance similar projects for Hong Kong and PRC comics, because there’s a lot of great stuff from guys like Nie Jun and Golo Zhao that is already available in Chinese and French but not yet translated into English. A good way to keep updated on developments in Chinese comics in translation is to follow me on Twitter, since I usually do a sweep of the latest developments every couple of weeks. I haven’t been writing about comics as much as before, since I’ve been branching out more into translating literature and film (and actually music, too) but comics are still a big passion of mine. Another good person to follow is Orion Martin, who also works as a translator and promoter of Chinese comics in translation, especially underground and experimental stuff. Some of this shades into the contemporary art scene, so I’d also recommend checking out LEAP: The International Art Magazine of Contemporary China, which Orion and I both translate for on a pretty regular basis.

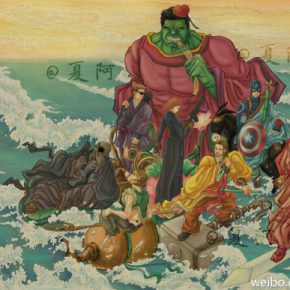

AVENGERS AS THE EIGHT IMMORTALS BY XIA AH 夏阿

Finally, if you want to read Chinese comics from the 1930s, John Crespi at Colgate University has persuaded the library there to host the entire run of Modern Sketch, which they’ve made available to whole world, free of charge. For stuff from the 1940s and 1950s, there is the Hunter collection, which has a crazy origin story—basically it’s the source materials for ‘journalist’ (aka CIA spook) Edward Hunter’s polemic Brainwashing in Red China: The Calculated Destruction of Men’s Minds. Very fun stuff to browse, especially if you imagine yourself doing so at the height of the cold war when comics were suddenly being treated like WMDs.

To learn more about Nick Stember’s research on Chinese comics, visit his website at http://www.nickstember.com.