I

PACIFIC CROSSINGS

David Lam in his Vancouver studio working on a large commission for the Hilton Hotel in Hong Kong, 1965. Photo courtesy of Rose Lam

In 1967, David Lam briefly returned to Hong Kong from Vancouver after being commissioned to complete a series of paintings. In an interview with The Star atop the rooftop of the Peninsula Hotel where he sat sketching, Lam explains the precarious situation of the wave of migrants who had already started leaving Hong Kong for Canada. Work in the cities was already in scarce supply, leaving only difficult jobs in the Interior and up north. Professionals who had lived good lives in Asia struggled to adjust. Lam was not spared. In his first years in Vancouver he worked with Woodward’s as a visual designer, despite his experience at the United States Cultural Centre, the Hong Kong City Hall Museum, and co-founding the Circle Group, to which many leading progressive artists belonged to.

Many of his works explore cityscapes. He has a love for the vitality that permeates Hong Kong which just did not exist in Vancouver. Despite this, there is a curious resonance between the paintings of his home city and his new digs.

Viewed from the distance, painted by the same hand in the avant-garde Chinese style, there is a strange similarity between both cities on different sides of the Pacific.

Throughout the interview there is no mention of the wave of riots and bombings that wracked the city the entire year, spurred on by the Cultural Revolution just north of the Sham Chun River. Instead, readers are asked to note the thick winter clothes that the Lam family is wearing in a photograph taken in Vancouver. They are picturesque representatives of the Chinese diaspora abroad as political anxiety continued to flood the city’s newspapers.

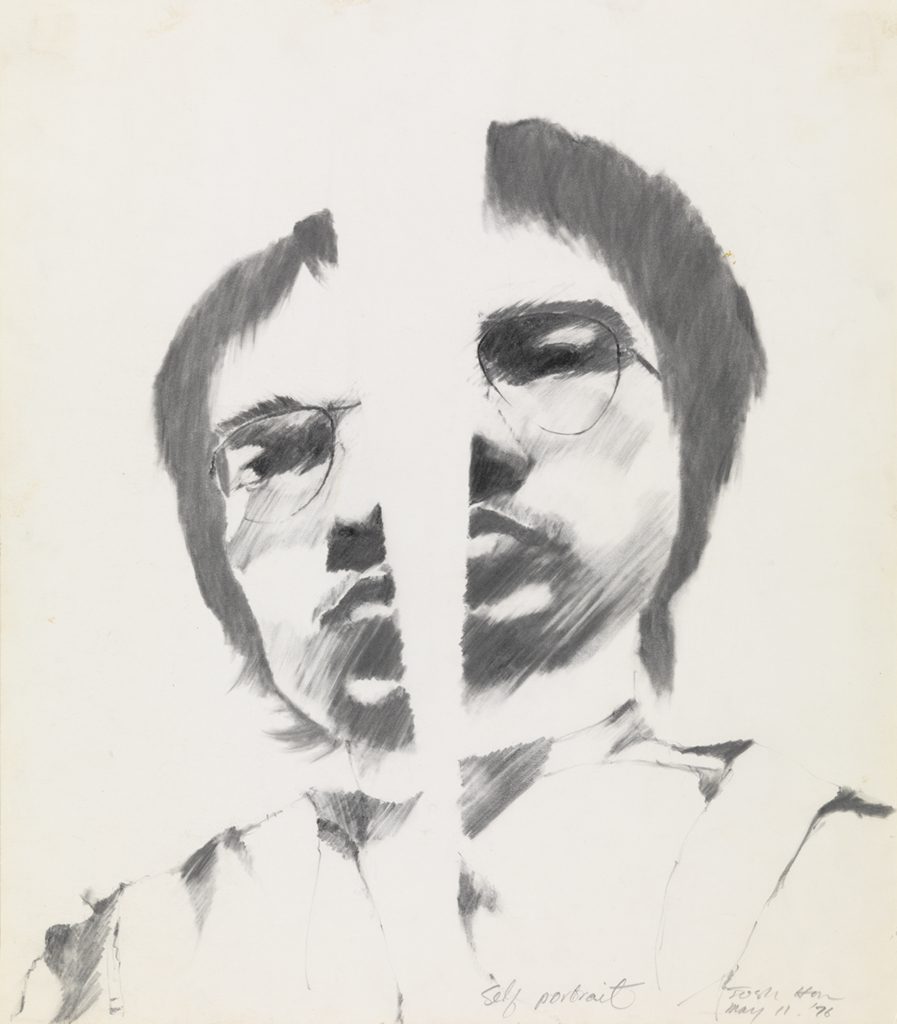

For Lam migration was still an open door, since he eventually began to produce art full-time after his first decade in Canada. For Josh Hon, currently a registered Clinical Counsellor in British Columbia, his disappearance from the art scene is painfully pronounced. Before Hon moved to Hope he had a brief but illustrious career in 1980s Hong Kong, becoming famous and earning acclaim for his use of mixed media and the incorporation of technology. His work with The Box, a theatrical music ensemble, brought together musicians, writers, and actors and simply overruled the conservatism of local institutions. After leaving, his fame faded with time. By the 1990s he was already in the Interior and had left behind a world where he had made such a large impact. Hon’s work depicting the unease of the time period would go on to be taken up by various artists in the lead up to the Handover. In the exhibition hall a large self-portrait shows him gazing solemnly down at visitors, his face cleaved in half.

Josh Hon. Self-Portrait, 1977. Graphite on paper. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

Traditional Chinese ink painting focuses on capturing the essence or spirit of its subject. Pure precision and faithfulness to details are not essential; rather, it is important to understand the impressions that the subject leaves in the minds of the observer. It is an exacting art, for mistakes cannot be removed or hidden, and every stroke must be deliberate. Carrie Koo cut her teeth with the renowned painters Chao Shao An and Hu Nien Tsu, before finally falling in with Lui Shou-Kwan, a pioneer of the New Ink Movement that questioned the wholesale adoption of Western techniques and called for a return to Chinese roots. This call led to a fusion of art styles that quickly became unique to Hong Kong. While her training under the painters formed the basis of Koo’s artistic ability, her new life in British Columbia and Alberta soon led her to change her art style. She found herself incorporating the scenery of western Canada into her new paintings. Winters and the cold appear to be a recurring motif in her work, appearing almost dreamlike in their execution.

Carrie Koo. Fading Moon, 2016. Chinese ink and pigment on paper. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

Peculiar colors and spreading ink fill blank paper with subtle precision.

Meanwhile, a specific branch of ink painting, the shan shui (mountain and water) style, was deeply regarded as being more philosophical than realistic. It was precisely this 1,500 year old style that Paul Chui studied alongside calligraphy when he was a boy growing up in pre-war Hong Kong. He was not content with working as a set designer for the Hong Kong Television Broadcast network, and later joined David Lam’s Circle Group before he moved to Canada in the early 1970s. His paintings do not represent landscapes as they are, but rather how he interprets them. In North Series #4, ice and cliffs loom against a gloomy landscape. They seem indistinct, just out of focus. Perhaps these hazy landscapes represent a sense of alienation amidst a place of beauty? I can only guess.

Paul Chui. North Series #4, 2013. Ink and pigment on paper. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

Perhaps it was partly the influence of the new style of art that a definite Hong Kong identity began to take shape. This sharply divided its people from their counterparts in Mainland China, especially the way the city’s cosmopolitan vibe jarred harshly with the fundamentalist Maoist movements of the Cultural Revolution that had wrecked thousands of years of heritage. All four artists would leave before the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, when uncertainty about the return of Chinese sovereignty raged high. This was a time when fantastic rumors spread, with foreign property and currency steadily amassed. It was also the start of the end of a generation of artists.

II

RETAINERS OF ANARCHY

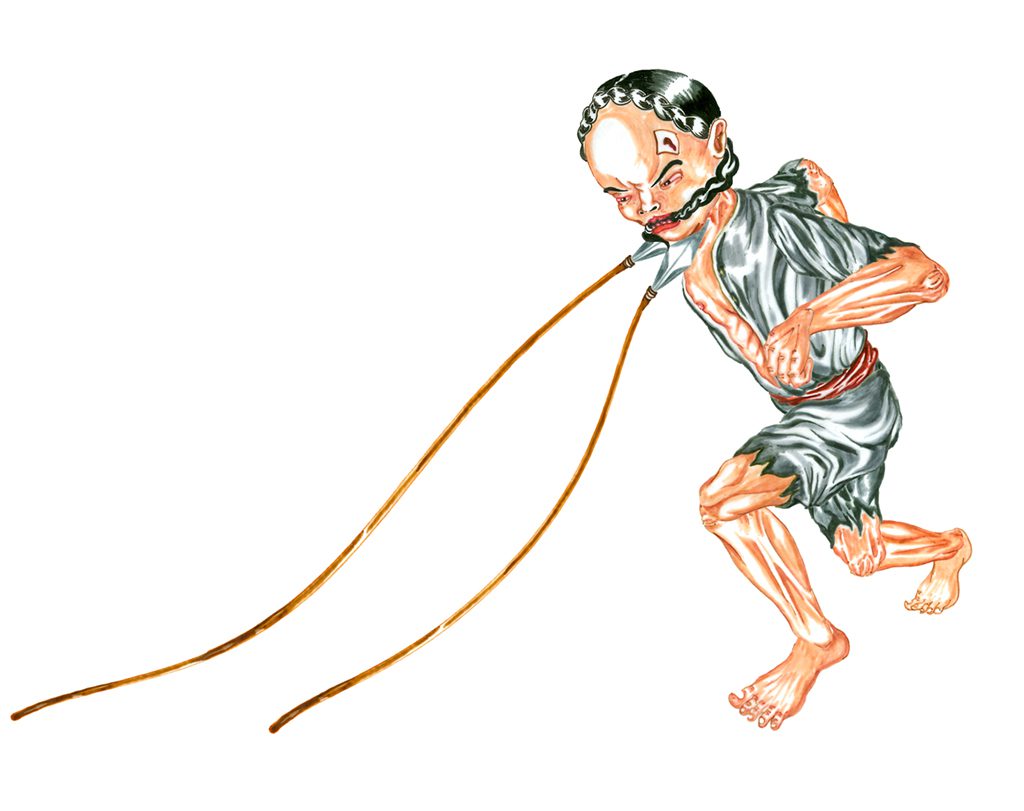

Howie Tsui has led a life of relative fragmentation which has transported him from Asia to Africa and eventually North America. Like the rest of the diaspora he carries memories of a home that he knew briefly, fragments waiting to be transformed into a statement. In Retainers of Anarchy, the legacy of Chinese art, folk legends, cinema, and identity crises play out on a twenty-five metre screen. It draws on Tsui’s experiences with the grandiose River of Wisdom, produced by the People’s Republic for the Expo 2010 in Shanghai. It was just the latest adaptation of the famous Song Dynasty scroll painting, Along the River during the Qingming Festival, which was subsequently adapted and interpreted in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.

In stark contrast to the gentle grandeur of the original painting, Tsui’s work is monumentally disturbing.

Recognizable political and cultural dissidents are tortured, endlessly living out their punishments on loop, as if trapped in a Chinese depiction of hell. A woman wielding an umbrella holds off the stream of words from a loudspeaker, propaganda fired like machine gun bullets. The self-satisfaction of River of Wisdom is satirized in the centrepiece of the digital scroll. It features Kowloon’s Walled City, which until its demolishment was a functioning settlement that operated relatively independently of the rest of the city.

Howie Tsui. Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Key frame drawing for algorithmic animation sequence. Courtesy of the Artist

It is funny just how the Walled City, which was built as a refuge for Qing Dynasty political refugees, rapidly evolved from pure anarchy into relative order. But if order can exist in anarchy, Tsui posited that it is therefore possible for anarchy to exist in order. Such is the world outside his Walled City, where nothing makes sense. But inside, in some rooms at least, there is peace and normalcy. The City is an effective stand-in for Hong Kong, which can be so insular yet so aware of the encroaching confusion of the outside world.

Pacific Crossings runs until May 28 at the Vancouver Art Gallery, featuring the art of David Lam, Carrie Koo, Josh Hon, and Paul Chui. Retainers of Anarchy, a solo exhibition by Howie Tsui, runs until the same date. For these exhibitions, the VAG also collaborated with the Asia Art Archive to provide a broader context of Hong Kong’s art scene in the second half of the 20th century. Ricepaper wishes to thank the VAG for giving us access to the exhibitions.