Kai Cheng Thom, photo by Jackson Ezra

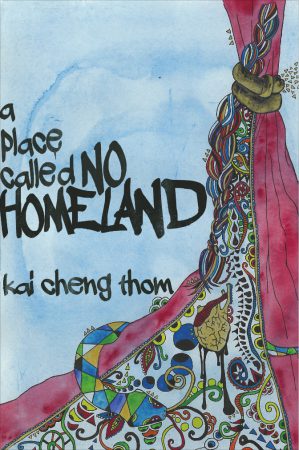

Kai Cheng Thom is a poetic force of nature. The twenty six year old Chinese diaspora kid comes from three generations of settlers of colour from traditional Salish and Musqueam (Vancouver) to Kanienkehake (Montreal) territory. Her heritage is infused into the words she puts on the page, and it is passionately expressed when she performs her poetry. With the release of her debut poetry collection, a place called No Homeland, we caught up with Kai Cheng to discuss the place called No Homeland, how her past influences her writing, and what it’s like creating material for the page as spoken word artist. (We even got a bit of news on her children’s picture book).

Who is Kai Cheng Thom and how does telling stories shape your identity?

My parents are both Toisan yahn, meaning that our roots are in the Guangdong province of China, and that my heng haa hua (ancestral language) is toisanhua, or toisanese/taishanese. I write in English, though I also speak English and Aantonese. I used to say that I belonged to queer, trans, Chinese and activist communities, but now I believe that I belong to my family and to myself—no one else. I found writing and storytelling through necessity; they were what I needed to live. A dear friend brought me to a slam poetry show when I was 20 or so, and I knew then that I had found a place where my art could grow, though I’ve since branched away from slam. My writing owes a lot to the traditions of oral storytelling and performance poetry, and especially to performing poets who taught me, including Deanna Smith, Jason Blackbird Selman, d’bi young anitafrika, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarsinha.

a place called No Homeland, Arsenal Pulp Press

What is the place called No Homeland? How did you come up with the title?

From the moment that I started gathering pieces to create the manuscript, it was pretty clear that a place called No Homeland was the right title for the collection. It’s drawn from a line in the first poem in the book, which is about growing up in Vancouver as a “juk-sing,” which is Cantonese for “hollow bamboo.” “Juk-sing” means that you have a body without a spirit, that you exist without direction. There’s an insulting term for pretty much everything in Cantonese. a place called No Homeland is the place that we exiles, children of diaspora, those who belong nowhere, carry inside our bodies. It’s a place that others may call empty, but that is in fact full of pain and poetry and possibility.

The place called No Homeland is my response to the context of colonization, neo-nationalism, and queer homonationalism that I was born into—the pressure to conform and assimilate, to allow my body to be used as the justification for colonial violence. I don’t need to prove that I am white enough, or Chinese enough, or queer enough for any one or any place. My homeland is my body, is my family, is my relationships, is my heart.

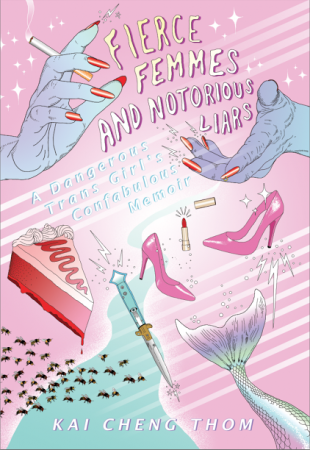

Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir, Metonymy Press

a place called No Homeland is definitely a no-holds-barred collection—you don’t shy away from being honest about how you’ve experienced being a transgender Asian artist. How important was it for you to speak truthfully?

Truth-telling is the most important thing —it’s the principle around which I organize all of my artistic work. I think that this is pretty funny, because I used to have a terrible compulsive lying problem as a child (I’m better now…I swear!) I’m obsessed with truth and lies. The title of my first novel is Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars. I think that this is because, like many trans and queer people, I grew up in a context where lying about myself—my desires, my identity, my needs—was an absolute necessity in order live.

When you are forced to tell lies about yourself, over and over, you lose your grasp on the truth. And at the same time, queer and trans and racialized individuals are bombarded with lies about who we are from the society around us—that we are sick, bad, ugly, less worthy. I started writing poetry in order to find my back to the truth, to find my way back to myself. It’s how I hold on. It’s how I survive.

Your roots are in spoken word poetry, so how was it different for you writing poems for the page, was the process difficult or eye-opening in any ways?

I started out in spoken word, basically because the “literary” poetry scene was too white and inaccessible for me to break into at first. I believe that poetry should honour its roots in the oral tradition, whether it is meant for page or stage—the oral tradition being a commitment to accessibility, integrity, body, and context.

It was really fascinating to go through the formal editing process because I have never studied creative writing formally—my teachers were poets and audiences at slams. In many ways, the editing process triggered internalized shame about race and class, which was really important for me to work through. I learned how to take criticism from white, established editors without totally collapsing before it. I learned how to tell the difference between advice that honoured my pieces and advice that was aimed (intentionally or unintentionally) at shaping me into whiteness.

What are three things you want readers to take away from the collection? And what’s something you wish to tell a younger Kai Cheng Thom?

1) Integrity is better than beauty

2) Truth is more important than politice

3) Love begins with yourself

[I’d tell my younger self to] be kind to yourself. Practice your Chinese more often. Do not sleep with boys to whom your body means nothing unless their bodies mean nothing to you. Stay away from the internet. Only you can stop forest fires. And only you can start them.

‘dear white gay men,’ ‘between friends,’ and ‘your white cisgender boyfriend can’t save you from the end of the world’ are probably my favourites. They really don’t sugar-coat what you’re trying to tell. What are your hopes for the Asian LGBTQ individuals in the future?

We really learn to love each other and ourselves! Without undercutting the work of many passionate and important Asian LGBTQ actvists, Asian queers really struggle to find a sense of identity and solidarity. This is because of many historical, cultural, and political factors, but the upshot is that (particularly light-skinned) Asians are always finding ourselves trying to occupy this strange middle ground of “model minority,” supposedly economically ascendant but culturally exoticized, not quite as racially oppressed but certainly never white. We’re used as a bulwark, a measuring stick against that other people of colour are held to racist standards of assimilation—which many of us participate in, because getting close to whiteness feels like getting close to safety, to being loved.

In the Canadian/American queer community, Asians are devalued and invisibilized, and so frequently pitted against each other! How many times have I found myself in competition with other Asians for white approval, white spaces, white sex? We are the best at dehumanizing each other. I want us to find our inherent value and beauty and power—to find each other gorgeous and sexy and deeply, deeply interesting. I want us to rush into new and exciting places with our stories and our art. Asian diaspora doesn’t have to be about feeling trapped between past and present—it can mean embracing all of our different, disparate pieces to pave a road toward the future.

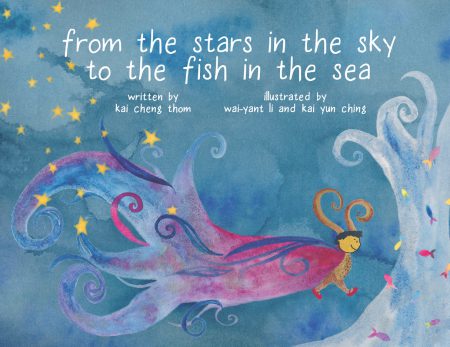

From all the Stars in the Sky to all the Fish in the Sea, Arsenal Pulp Press

Any more books we can expect from you in the future?

The wonderful people at Arsenal Pulp Press are putting out a childrens’s book that I wrote called From the Stars in the Sky to the Fish in the Sea this fall. It’s a collaboration with two of my dearest friends, Kai Yun Ching and Wai-Yant Li, who are also of Chinese descent! It’s about a little child who is born when both the sun and moon are in the sky, and so they cannot decide what to be. I’m really excited about it.

Kai Cheng Thom’s website: https://ladysintrayda.wordpress.com/