The following is a personal letter from Paul Yee written to Jim Wong-Chu shortly after Jim’s stroke. With permission from Paul, the letter is published in its entirety here. Jim passed away peacefully on July 11, 2017.

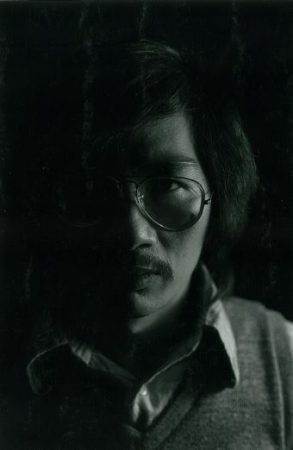

Photo by Jim Wong-Chu, courtesy of Paul Yee

Hey, Jim

It’s Paul, Paul Yee, shouting out from Toronto.

When I got over the shock about your latest news, I said to myself, “Jim, you’ve got to come back to us. People across the country, and around the world, are rooting for you. You’re an indispensable part of many lives and communities, and you are much loved.”

In the 1970s, when you and I first met, you had so many different circles of people that no one person really knew the “complete” you. This was part of your mystique, being worldly, having an artistic vision, and owning a multi-faceted skill set that surprised all your friends.

Back then, you were a few years older than me, (you are still are, and I want this situation to continue for a long, long time). I was still a student, and Oh! how I envied you. You worked full-time, you had a steady income, you drove a Datsun 240Z, and most importantly, you had freedom to do whatever you want.

Doesn’t everyone yearn for independence?

Jim Wong-Chu

You were an early pilgrim to San Francisco, where you met kindred souls in the arts and community politics, people like Corky Lee, Nancy Hom, and Jim Dong. You sensed first-hand the rising energy and potential in the Asian communities of America. You brought back books, posters, artwork, music—to inspire us to look beyond our local horizons.

You were one of the few young people to have a “place” in Chinatown (though I often wondered how you found parking). Your studio at 15 East Pender, with its low ceiling and dark back rooms let photography happen, let Pender Guy get started, and let people hang out somewhere safe and cool. You didn’t live there, but you paid many years of rent because your instinct said, “Jim, you need to be there.”

You’ve always been a free thinker. Remember when you wouldn’t buy a membership in the Chinese Cultural Centre, then the brash new player in town, because you wanted to be an outside observer who could keep criticizing it? Chinatown fought many issues over the Firehall, Barbeque Meats, the Green Paper on Immigration, etc., but you, you always chose your battles carefully. Didn’t you go through a phase of reading and re-reading Sunzi’s The Art of War?

Wait, let me to go back to your circles of friends.

You were/are fluent in Cantonese, so you had Hong Kong friends: the Manson brothers, the many beautiful women whom I only saw in your black and white photographs, and the skinny kids who called you “sifu” because you taught them gung-fu. You always had the newest “fringe” magazines from Hong Kong about art and politics because the discussions over there also seemed far advanced than our local situation.

Back then, as now, you have many artist friends, Alvin and Cecilia, Ron Yip, Ho Tung. I’d see your works framed and hung on walls at art exhibits. Most of us, we were volunteers, we were curious about Chinatown, but we sure weren’t artists. You were one of the few artists that we knew. And your artistic vision drew people to you, young people who were curious about you and, in turn, who were encouraged by you, people like Helen Koyama, Barry Hong, Artson Seto.

You and I, we met in Chinatown. You wanted to run a “grass dragon” for the mid-autumn festival. People here knew nothing about it, but you were one of the few people who had seen it in China, and you convinced a bunch of people to help: to cut grass, weave a serpent-like body, build the dragon’s head, and to light this magical beast with incense sticks and run it along Pender Street. That grass dragon has never been done again. It’s one of my best and strongest memories of Chinatown.

Jim Wong-Chu

Back then, we young people cultivated long shaggy hair and wore bell-bottom jeans and tie-dyed T-shirts. You designed several silk-screen logos for Pender Guy’s T-shirts, one of which featured the all-time hero Monkey King.

Here’s the thing. You have a vision, you have a huge sense of community, and you’ve long been moving it along, on your own and with kindred souls.

You documented us with your photographs. You met tons of people in your daily swings through the markets and eateries of Chinatown. This was our “community,” people from here and away, speaking only Chinese, only English, or maybe both. You saw these people often, they trusted you, shouted out greetings, made room for you, and let you take intimate photos of them at work.

Those images were honest and true: Chinatown was about people and work, history and belonging. In the faces of your subjects, you caught forever their hopes and dreams, and their life wisdoms, all of which were part of what it meant to be Chinese Canadian at that time.

You collected Chinatown. During one of many demolitions on Pender Street, you rescued two second-floor windows, old glass in ancient wooden frames, with two Chinese words painted boldly in gold to be seen from the street. The two words were “sieu heen.” Translated, they meant “laughing corner,” which was a private gambling club. My uncle was a member for decades, and he went there every day. That was his way of making a living.

You have an insatiable curiosity about making things better. When you discovered how yeast posed a danger to the human body, you told everyone, “Stop ingesting it!” When you learned about curcumin, you handed out pills and said, “You gotta try this. This will really help!” You found a talented masseuse newly arrived from China, and dragged me to see her because of my sore shoulder. The treatment made me scream with pain. And now you’re into brown rice and organics. So, tell me, why didn’t you ever get into yoga, when you had Marlene right there for you?

Your eye was unparalleled in the photographs you took. That precious gift established the humanity and universality of the people and places you were drawn too. A single photo of yours was worth far more than “a thousand words.”

But, then, you got into words. You pushed the envelope and broke out of the darkroom to go study poetry and write. You impressed the noted poet Michael Yates, and published Chinatown Ghosts with Arsenal Pulp Press, our publisher in common.

Do you see that your art is traveling full circle, going from images to poetry, and then returning to pictures when your words sketch out rich, personal worlds in the minds of your readers?

The photos and words gathered in your portfolio “Pender Street East” was spectacular. It’s a collector’s item, and I’m glad it’s safe in the archives.

You care about history and you care about stories. You and Pender Guy radio went out to document the stories of the Chinese on Vancouver Island, as well as the record of Chinese Canadian veterans in the Second World War.

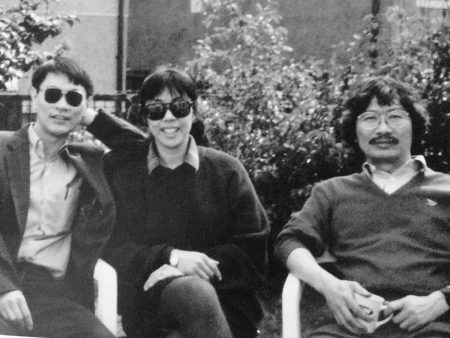

Paul Yee, Sky Lee, Jim Wong-Chu

You recognize the power of words. Stories need to be published to reach audiences, so you pushed the anthologies of Chinese-Canadian writing, the Asian Canadian Writers Workshop, Ricepaper Magazine, and the annual LiterAsian conferences.

You know everyone in the literary community, but you also have a keen eye for writing. Remember when you read my early outline for A Superior Man? You saw that my ending didn’t work, and told me so, early on, so I changed it and saved myself much embarrassment.

Mohamed says hi and recalls how you and Marlene stayed with us in August 2003 during the great power outage in Toronto. For once, it was dark enough for people to lie on the grass and gaze up at the stars. Then, at dinner with Dora Nipp, we talked and laughed and there wasn’t a moment of silence.

Jim, you and I didn’t always agree; we’ve had long, loud arguments at meetings and over the phone. There were times when I couldn’t understand you, you didn’t understand me, and we had to agree to disagree because of our different communication styles. But we stayed friends because we’re moving, forward, in an unstoppable movement that is way bigger than the both of us put together.

Jim, you started many things and there’s much more yet to be done, so come on back to us. Soon.

2017 03 19

Paul Yee is a Chinese Canadian historian and writer. He is the author of many books for children, including Teach Me to Fly, Skyfighter, The Curses of Third Uncle, Dead Man’s Gold, and Ghost Train — winner of the 1996 Governor General’s Award for English language children’s literature. In 2012, the Writers’ Trust of Canada awarded Paul Yee the Vicky Metcalf Award for Literature for Young People in recognition of having contributed uniquely and powerfully to our literary landscape over a writing career that spans almost 30 years.

1 comment

Paul, thank you for sharing your thoughtful and insightful letter to Jim. It was a pleasure to read and to learn more about Jim. He indeed had many circles of friends. In the mid 90’s and early 2000’s, I was in the Asian Heritage Month Society executive circle as well as the occasional “you’ve got to check out this new Chinese restaurant” circle. Jim’s insatiable curiosity of all things Asian Canadian, literary, pop culture, culinary and health would create circles that would ripple to every corner of the globe. I was always impressed with his encyclopedic knowledge of Asian Canadian history. He would always start with “did you know that…” to be followed by a piece of Asian Canadian history that I have never heard of. Who needs Google, when we had Jim! I was as shocked by anyone whom he’s shared a piece of history or advice about the benefits of eating cayenne peppers when he passed so very suddenly and oh so unfairly soon after his retirement. He had so much more to share. I only hope he had time to put his thoughts to paper. He is and will always be missed by the Asian Canadian community whom he championed in his many circles.