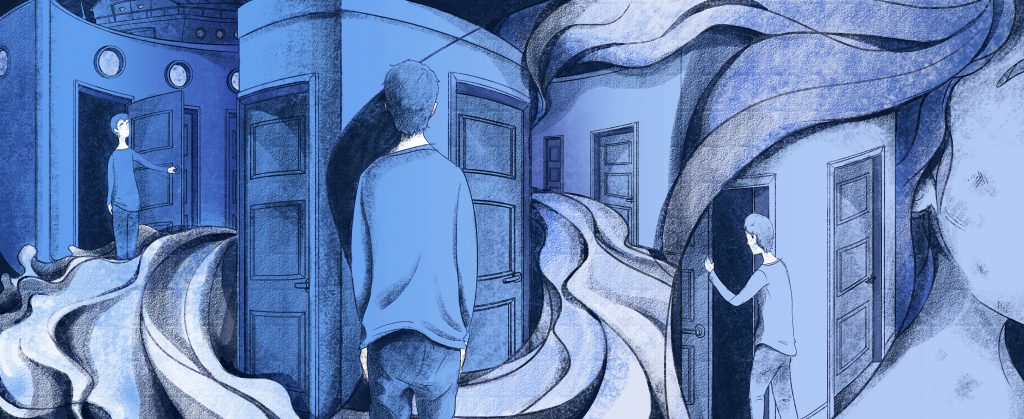

Illustration by E. Joan Lee

Just like that you are awake and the red lines of the radio-clock sketch 02:17 in the dark. Mind takes a minute to remember where you are. The switch for the bedside lamp is helpfully illuminated, a gentle glow that blossoms as you touch it into warm amber light, revealing a tasteful lavender bedspread, walls the colour of wheat. Your glasses are where you left them, on top of your book.

What pulled you so abruptly from sleep – residual jetlag, or a dream? But you’d remember that, the sense of falling, the jolt of the ground. You drain what remains of your bedtime water glass and then hear again the sound you now remember slicing through unconsciousness, a sharp thump, muffled but definite.

Tempting to sink back into the goosedown pillow, but you know sleep will not come so easily. If only you had brought more pills. Padding to the door, you make sure you have your keycard and step outside. The corridor stretches in both directions, bending away at either end. By the tasteful lamps you can just make out the rows of gleaming doors with discreet brass numbers.

Another thud, something shattering. Voices that aren’t raised exactly, but heightened. At least two of them. You take a couple of steps in one direction, then the other. Impossible to trace the source in this tube of soft furnishings and carpet. You wait, but no other doors open. It seems no one else can hear, or wants to.

You could go downstairs, but not in pyjamas. Far too much trouble to get dressed. Call down, then? Again, you hesitate. Not all the night staff, you remember, speak much English. How to convey something imprecise, just a sense that things are awry, that help might possibly be needed?

Then again, the locals speak in quick, excitable tones, and most conversations here sound like arguments to you. Emphatic gestures and furrowed brows. Is this just a high-spirited chat? Or could it be a film? But it isn’t, you know it isn’t, you can tell this is real life.

You do not belong here. People have their own ways of dealing with things. You travel a lot for work, and seeing so much of this part of the world has convinced you it’s never worth getting involved. There is resentment about people like yourself appearing to interfere. The first time someone called you neo-colonialist you were startled. Now you take it in your stride, joking that you’re just passing through, a gunboat’s on its way.

Nothing more to do, then, but drift back to bed. High thread-count sheets and quilted comforter absorb you, a warm place that remembers your body from a minute ago. You listen vaguely for more sounds, then no time at all seems to pass before your phone alarm blips and you open your eyes to vicious sunlight.

***

You’ve done this enough times to have your routine nailed. Suitcase already packed, left ready by the door. Your travelling outfit on a hanger, online check-in done. You stride out for yet another hotel breakfast, hoping this place will have that cereal you like.

A man stands next to a tiny woman by the lift. They are speaking the local language as you approach and even before you can think ‘It’s them,’ she has turned to give you a swift, anxious glance. Her face is bruised, although she has covered the worst of it with make-up. There are blotches on cheekbones and nose. You smile at her and she responds tentatively, the corners of her mouth twitching up slightly.

Standing with them in silence, you wonder if they are thinking, like you, that they might never see you again, that all of life is these long itineraries that may or may not intersect with other people’s. And even when they do, all you can do is walk alongside for a short time and see what happens next.

She lets out a tiny gasp, which you might not have noticed if you’d been a step farther away. You see the way he is holding her hand, pushing her middle finger back, farther than it looks like it would go without snapping. She is doing nothing to resist, just looking at him with wide eyes. He says a few things to her, his voice hoarse and heavy as it was last night, before he releases her. She remains still, clutching the painful hand.

And still you say nothing, do nothing but watch, hoping this is all, that she will be safe. Is she his wife, his daughter? Who can say how things work here. Perhaps this is normal. As they leave, she turns and looks at you in such a way as to melt you, just for a moment, before disappearing into the busy street. You notice the man has his hand around her wrist, as if to keep her from escaping.

So you travel onwards, thinking already of the next destination, what you should do on your layover, where you should eat. You go to so many places, it’s hard to claim they all mean something, let alone all the people you encounter. Take this woman – but the idea of trying to dissect what you witnessed feels impossible right now. So you silently wish her luck, and get on the train to the airport, quickly losing yourself in the documents for your afternoon meeting. By the time you arrive, you have forgotten her face.

Jeremy Tiang is the author of State of Emergency (2017, finalist for the 2016 Epigram Books Fiction Prize) and It Never Rains on National Day (2015, shortlisted for the 2016 Singapore Literature Prize). He won the Golden Point Award for Fiction in 2009 for his story “Trondheim”. He also writes and translates plays, including A Dream of Red Pavilions, The Last Days of Limehouse, A Son Soon by Xu Nuo, and Floating Bones by Quah Sy Ren and Han Lao Da. Tiang has translated more than ten books from the Chinese—including novels by Chan Ho-Kei, Zhang Yueran, Yeng Pway Ngon and Su Wei-chen—and has received an NEA Literary Translation Fellowship, a PEN/Heim Translation Grant, and a People’s Literature Award Mao-Tai Cup. He currently lives in Brooklyn. You can follow him on Twitter @JeremyTiang

Illustration by E. Joan Lee. You can follow her on Instagram @ejoan.lee