In the final part of William Tham’s ‘Java Quartet’-a series of four stories from Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and Surabaya inspired by the books by Pramoedya Ananta Toer, he looks at the Ijen Crater on Java’s east coast, which is home to both a huge sulfur mining operation and the famed blue fires which draws tourists from all over the world.

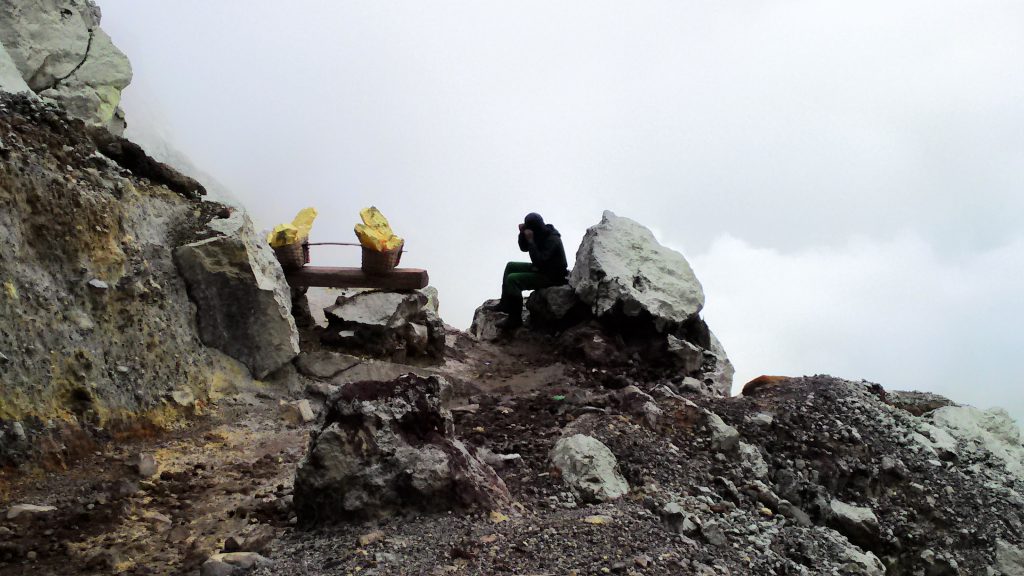

A sulfur miner taking a rest.

Ijen means ‘alone’ in Javanese.

This was the old name given to the vast crater when locals first stumbled upon it. In the centre of the rocky caldera was a lake, a shimmering beautiful turquoise but acidic enough to burn one’s skin. Above it clouds of sulfur collected, forced out of the earth by a series of pipes leading from the ground before terminating and solidifying at the surface.

Here the miners of Ijen set to work.

The volcanic highlands of eastern Java terminated there at the island’s seaside, in sight of Bali’s western coast. Farms thrived on the fertile soil and farmers led pastoral lives, quietly ending the day playing the guitar by the paddy fields while the call to prayer issued from the many mosques. But up in the chilly mountains the miners led different lives, risking their lives to mine sulfur at Ijen.

Hadi, our guide, explained the situation carefully as we began our nocturnal hike up the mountain. The tourists were already swarming the place, eager French and German visitors with knapsacks and headlamps hiking up the cold slopes. In the darkness the coffee plantations were invisible, and only the weak glow of our torchlights picked out the narrow trail. Indonesian sulfur is known for its purity and quality, and Ijen is where a vast bulk of it is produced. Even at two in the morning miners with trolleys were already on their way up. Some of them wore masks, but many had hardly had protection at all. The hardier miners, used to the choking clouds of sulfur that clouded the air, only used a damp cloth tied around their noses which was clenched between their teeth. Already there was an easy camaraderie between the miners and the guides, joking and guffawing while sleepy tourists trotted past.

“The government opened this up, and now they charge an entrance fee. This is still a miner’s path…if you see one you must let him go past. Otherwise, he might fall off the edge of the cliff. It’s a long way down.”

“And who buys the sulfur now?” I asked, pulling on my jacket and adjusting my gas mask as we paused outside the canteen where snacks and coffee were sold to the laborers.

A nearby miner guffawed in the near-darkness. “Orang Cina!” he exclaimed. The Chinese.

The miners would bring their trollies up to the rocky edge of the crater, before descending with carrying poles and baskets. At the end of their downhill journey they extracted the sulfur, painfully carrying it back up the slopes and into the awaiting trolley. For each kilogram of sulfur carried down the hill, they are paid 975 Rupiah. At the time of writing this works out to around ten Canadian cents. A tough miner can carry between seventy to eighty kilograms per trip. Most make a couple of trips a day, and some wake up at the crack of dawn so that they can make three. A productive miner can therefore earn up to $24 a day at this rate.

Work is grueling and conditions are harsh, breathing in the stench of concentrated sulfur. And the miners do this in full view of the tourists, armed with expensive cameras and rolls of hundred-thousand Rupiah bills in their pockets, ready for their next destination in Bali or Bangkok. People from two worlds collided on that rocky path to Ijen. This was the dark side of postcolonial Indonesia, the hardscrabble lives of the workers contrasting eerily with the tourists and rich locals.

Blue flames.

We descended into the pit. We had seen the stars in the sky above on the way up and the flash of distant lightning in the clouds, but at the top clouds of sulfur were rising around us as we snapped our gas masks on. The trolleys waited like patient dogs as their owners began their descent. A sign warned AWAS! Danger! Sometimes a toxic gas rose from the depths of the lake. Whereas sulfur had the unpleasant smell of rotting eggs, this one stank of a decaying corpse. At the first whiff you had to run, back up the slopes as quickly as your legs could carry you.

“I’m not going!” A German lady barked from in front of us, despite her guide assuring her of her safety. “I won’t go down there.”

I sucked in the putrid air, cautiously climbing down the steps and taking in the sight. A row of headlamps stretched down into the darkness, shining faintly through the smoke. Blond children who would go to school in Paris were rubbing shoulders with rich Mainland Chinese tourists. In the far distance the blue flames that made Ijen famous leapt up, flaming clouds of sulfuric gas blazing wildly as cameras flashed incessantly. Strangest of all was the sight of the workers, carefully threading their way past the visitors in search of sulfur.

The descent was slow; it ground our knees as we slowly picked our way into the crater. In the darkness you could hardly see and the rocks wobbled under our footsteps. If you slipped you would simply fall over loose rock down to the crater. Medical attention would be basic at best. My eyes began to sting–we were still so far away but the clouds of sulfur were like a toxic mist.

At last we made it to the edges of the crater, the flames issuing from unseen places behind the smoke. The sulfur emanated from pipes installed into the ground. Hot gas condensed on the inner surface of the pipe into an orange liquid, which later solidified into a yellow rock. This was what the miners picked up, tossing the jagged pieces into their baskets before climbing back up.

The wind changed direction. All of a sudden the clouds of sulfur, which had until then been drifting skyward, enveloped us in a choking haze. I was coughing bitterly, my throat was on fire and I couldn’t see, shutting my eyes as tears began welling up. For a horrible instant I could smell nothing but the rotten egg stench and my brain was screaming that I was going to faint amidst the terrified tourists who were trying to back away from the pipes. I crouched down, holding my breath, waiting for the clouds to clear, and then light-headedly began edging my way away from the pit.

Meanwhile the miners, hardened by their years of experience, walked down past me and into the clouds.

The acidic lake in the caldera.

The sun rose as we sat down on a rocky outcrop, pleased to be rid of the worst of the stench. Since 5.30am the sky had gradually brightened, the blue flames vanishing to reveal the menacing acidic lake that filled the Ijen crater.

“There,” Hadi said, pointing down at it. “In the old days the miners had sampans, rowing boats, which they would use to sail across the lake.”

“I heard stories about people dying here,” I remarked carefully. “A Frenchman fell into the lake once, right?”

“Ha! That’s an old story. He sneaked in before the mine was open to the public, he was happily walking on the edge of the crater when he fell down.”

As we waited my fingers slowly numbed in the chilling cold. Hadi took pity on me, fishing in his rucksack for a pair of gloves, where he kept the rest of the masks and scarves that he rented out at the entrance down below.

Hadi was not eating. It was the fasting month and he had already had his breakfast and performed his prayers before the hike began. His schedule worked out well for him. He took the tourists up to the crater, went back to his home in the nearby town of Taman Sari, slept, and awoke in time for breaking fast. For the miners it was a different story. They needed food for the energy to make the arduous climb from the lush hillsides to the edge of hell. God took a back burner for them.

On our way up the slopes, we stopped for souvenirs. An old man in a straw hat was seated astride his baskets of sulfur, holding up little figurines from sale. Molten sulfur was poured into molds and broken off-you had your choice of rabbits, Donald Duck, or roses. “Berapa, pak?” I asked, already knowing the price.

He smiled. “Sepuluh ribu.” Ten thousand each.

We bough three sulfur rabbits. The old man’s eyes lit up and he smiled-he only had a ragged collection of teeth left-and he happily threw in a final piece of sulfur for free. As we paid up, another miner walked past us, casually peering at our wallets. He chortled at the sight of lines of fifty-thousand notes.

On our way back out of the steep crater, towards the fires where guides and cold tourists huddled around, I frowned at the price.

Ten thousand rupiah per figurine.

That was the cost of hauling ten kilograms of sulfur back up the slopes.

Photos by William Tham.